Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (27 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

For easy reference, here is a list of the brain principles:

• Switch-costs are due to action.

• Action comes from backward inhibition (inhibiting old ways of doing things).

• Increased frontal control promotes action; early involvement of cognitive control is optimal.

• Multimodal brain regions are more plastic (i.e., change occurs when multiple perceptual stimuli are used).

• Self-involvement increases brain processing of information.

Memory and the Brain: Relevance to Change

The concept:

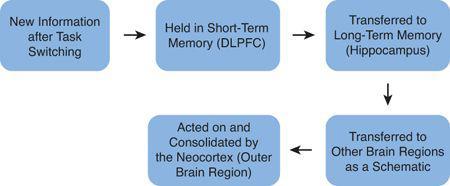

Human beings have to remember the details of the proposed changes in order to execute on them. Therefore, action requites proper functioning of memory. Memory may be either short term, intermediate term, or long term. Short-term memory is also called “working memory” and is processed in a network of brain regions. The DLPFC (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) is an important part of this network. The traditional view of how intermediate- and longer-term memories are formed is that the hippocampus is responsible for retaining newly learned information until it is consolidated in the neocortex (the outer layer of the brain). This view is increasingly thought to be outdated. A recent study showed that the original memory, which is hippocampus and context dependent, becomes transformed with time to one that is more schematic and independent of the hippocampus prior to modification by the neocortex.

26

This memory is therefore not locked in our memory vaults but is released in schematic form (like a compressed file) ready for action in the brain.

The model in

Figure 6.5

shows this functional anatomy in simplified detail.

Figure 6.5. Process of memory consolidation

We are increasingly finding that the brain learns information painstakingly, but that after that information is learned, it is converted into an “easy access” form so that it can be used with less energy than was used to form the memory.

The application:

It is easier to repeat past mistakes because long-term memories are stored in an easy-to-retrieve form and accessing short-term memories for actions is more difficult. Managers or coaches can say to leaders, “We need this much time in the exploratory phase to develop long-term memory; otherwise, your previous behaviors will keep on coming back to haunt you.”

Ironic Process Theory

The concept:

Ironic process theory is an interesting one that is well substantiated. The theory states that under situations of mental load or stress, we will often do what we are trying to avoid.

27

In addition, when people are trying to forget something in order to act, they are able to do this as long as they are not distracted or under mental stress of any kind. Trying to forget correlates with increased activity of the DLPFC and decreased activity of the hippocampus.

28

If attention is captured by stress instead of this energy-requiring task, people will be more likely to remember unwanted things. This can significantly interfere with action. In fact, we know that stress does prompt habit behavior in humans at the expense of goal-directed performance.

29

The application:

When you’re developing an action plan with a client, understanding actions or memories from the past is important to identify their reemergence at times of stress or mental load. Patterns that we want to forget reemerge when we overload our brains. Certainly, sports coaches are familiar with this phenomenon. Former major league baseball players Chuck Knoblauch, Steve Blass, and Rick Ankiel were famous for their sporadic wild throws, and Ankiel called his wild throw “The Creature.” When golfers are asked not to overshoot, they will do so under mental load. These errors are called “yips.” In the executive domain, managers, leaders, and coaches should be on the lookout for yips, and when they occur under time pressure or any kind of mental load, coaches should work with clients to reduce this mental load. (Part of the human

ability

to have yips may be due to the fact that reactions are faster than intended actions and may serve a protective function.)

30

The following language can be used: “Sometimes, when we try to suppress doing the wrong thing, we do the very thing we were trying to avoid. This is because our brains, under situations of mental stress, don’t have enough energy to suppress unwanted memories and they come flooding back.”

Here’s a list of behavioral factors that consolidate memories (enhance neocortical function):

• Power naps:

31

–

33

Power naps are brief periods of sleep (15-30 minutes) that give the brain a chance to rest. It has been found that these brief naps may be rejuvenating and therefore help register and consolidate memories.

• Emotions: Emotional arousal (positive or negative) that occurs within 30 minutes but not after 45 minutes of new learning.

34

Emotional memories have been associated with an enhancement in the recollective experience that was greatest after a delay.

35

This is only partly mediated by the hippocampus. Acute stress may strengthen the consolidation of memory material when the stressor matches the to-be-remembered information in place and time.

36

• Reward anticipation: Anticipation of rewards, depending on the individual level of reward-induced anxiety, can have either a beneficial effect or a negative effect on learning. There is a negative correlation between recall performance and anxiety ratings. That is, the higher the anxiety, the lower the recall, independent of reward anticipation. In other words, rewarding anxious people will not help them remember new factors in change. High-recall performance and low-anxiety ratings have been associated with enhanced activity in the midbrain dopaminergic centers, the hippocampus, and the amygdala. On the other hand, low-recall performance and high-anxiety ratings have been associated with enhanced activity in the anterior cingulate and middle frontal gyrus, brain regions that have been shown to be involved with anxiety and divided attention, respectively. A connectivity analysis indicated positive functional connectivity between the midbrain dopaminergic centers and both the hippocampus and the amygdala, as well as negative connectivity between the anterior cingulate and the amygdala. This indicated that excessive anxiety disrupted attention and memory consolidation.

37

The application (memory):

Excessive anxiety can disrupt memory when one is trying to change. When you’re dealing with anxious workers, they are not likely to remember many things. Integrating information after new learning is improved by emotional arousal but not if the stress is excessive. If it is, attention and memory will both be disrupted. The following language can be used: “The changes you want are very possible to achieve. But to get your brain to cooperate with your desired actions, we need your memory systems to be responsive at critical times. Emotions affect your brain’s attention and memory in a U-shaped curve....”

So, from this research, how can coaches or managers apply this knowledge of memory?

• Change requires holding onto new information. This requires a reduction of conflict with old information, thereby allowing new information to be registered and consolidated. You can therefore help executives elucidate the conflicts that the new changes bring about, thereby helping them bring these conflicts out of the unconscious and resolve them consciously.

• Change is prevented due to greater needs for energy utilization, as evidenced by having to go through the whole process of registering memories in the DLPFC (short-term memory center) against negative inputs from the amygdala (emotional register), basal ganglia (reward center), and ACC (conflict detector) and then transferring information to the hippocampus prior to it being held in a symbolic form while the neocortex consolidates this. This, as opposed to just recalling old habits already consolidated by the neocortex. If people avoid this process, they will choose to repeat old habits. You do not have to remember the brain regions here. But it is important to remember that more brain regions and more energy are needed for new learning.

• Optimal access to energy will facilitate new learning and change. Therefore, adequate sleep, daytime power naps, and appropriate emotional arousal are critical to faster, more efficient new learning.

• Rewards do not promote remembering in highly anxious individuals. First work on the anxiety, and then implement the rewards. Help executives outline exactly what about the new changes makes them anxious. (High anxiety will increase amygdala activation and decrease ACC activation needed to attend to the task at hand.)

•

Teach new changes in a way that involves the person’s emotions. Emotions consolidate memories and improve learning.

• Learning onsite and in real rather than just imagined situations is more likely to lead to consolidation of memory and thereby promote change.

The basic neuroscientific principles related to memory and change are as follows:

• For change to occur, the new process has to be remembered.

• Remembering occurs in steps: first short term, then intermediate term, and then longer term. Reducing conflicts with old tasks will help the client remember new tasks. Make these conflicts conscious.

• The brain will tend to remember things that are reinforced in an emotional context. Therefore, for change to be successful and for the various brain regions to consolidate memory, emotions must be involved. This can be done by involving a person’s imagination or experience and through the use of examples. Some people will use tools such as music or visual aids (such as pictures) to enhance learning.

• The brain will not register rewards for the new changes if there is high anxiety.

• Old habits require less energy. New habits require more brain processing and therefore new energy.

Action and the Brain: Relevance to Change

The concept:

Most managers, leaders, and coaches realize that unless change is self-initiated or starts from within, it is a very difficult process to undergo, in part because it is so painful. A long time ago, scientists believed that this was in part because the brain was hard-wired in childhood, and that asking people to change in adulthood was impossible. Recently, it has been proven that this in fact is not true. Although most circuits have already formed in the brain, it has been shown that the right kind of behavioral intervention can actually change the way in which the brain is wired. Often, this requires

practice, and in its most effective form, requires both a change in thinking and emotions.

Research has shown that when people make decisions that require moving from one situation to another, they will most often change their attitudes so that they view the new decision more positively and the old decision more negatively.

38

,

39

Harmon-Jones et al. (2008) provide this example:

“...imagine ‘Leon,’ who has been offered jobs with two different companies. The position offered by one company is more intellectually stimulating, but the other company has friendlier coworkers. One company is located in a city with a pleasant climate, but the other is in a city with a reasonable cost of living. Leon sees both job positions as similarly attractive, although they are quite different from each other, and he must decide between them. Once Leon makes a decision, he will need to perform actions in order to follow through with his decision. He will need to relocate, learn new duties, and perform well at them. After his decision, if he continues to see the two positions as similar in attractiveness, he may experience excess regret, which could inhibit him from effectively following through with his decision. However, if Leon is able to reduce dissonance, so that he views the chosen position more positively and the rejected position more negatively, then he will likely perform the job better and be more satisfied. In contrast to models of cognitive dissonance that view dissonance processes as irrational and maladaptive, the action-based model views dissonance processes as adaptive....”

40

Thus, cognitive dissonance (what one holds to be true versus what one knows to be true) is essential in certain circumstances. This is akin to closing some doors when you open new ones. Holding all doors open may inhibit change.