Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders (4 page)

Read Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders Online

Authors: Srinivasan S. Pillay

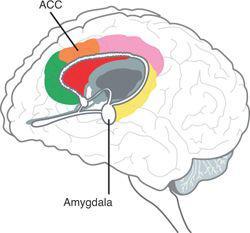

Among its many other functions, the ACC is the error monitor in the human brain. It is useful to think of it as a flashlight that is constantly searching for conflicts in priorities. Aside from error detection, it is also involved in anticipation of tasks, motivation, and modulation of emotional responses. It shares rich connections with the amygdala, reward pathways, and the rest of the frontal cortex. When the amygdala is chaotic, the ACC also becomes chaotic, and attention to things

both internal and external becomes chaotic.

18

Figure 1.3

shows the amygdala connections to the anterior cingulate cortex.

Figure 1.3. The cingulate gyrus and amygdala connection

The application:

When leaders are anxious, coaches can tell them that it is important to be aware that anxiety centers in the brain connect to thinking centers, including the PFC and ACC. The prefrontal cortex allows a person to differentiate among conflicting thoughts as well as determine good and bad,

19

better and best, same and different, and future consequences of current activities, thus working toward a defined goal and prediction of outcomes.

20

–

24

Therefore, when these functions are disrupted, thinking is disrupted. Effectively, by remembering that the amygdala is connected to the DLPFC, mPFC, and ACC, coaches can inform leaders that short-term memory, risk-benefit assessment, and attention are also disrupted by anxiety.

5. The leader has conflicts of interest

The concept:

Leaders may not be willing to face the fact that their conflicts of interest are affecting their decision-making. When there is a conflict of interest, one issue may cloud another because these internal conflicts may generate too much anxiety for the leader.

25

This may, for example, be very relevant in the merger and acquisition

process. The ACC, being the conflict detector, overactivates when this occurs, and action is stopped when this information is fed to the brain’s accountant (vmPFC). The accountant has to take its time dealing with conflicting information. An overt example of this (which is prohibited by the Securities and Exchange Commission) is when leaders have a personal investment in a company and their companies also have an investment in that same company. Thus, doing the best for the company may conflict with doing the best for that leader.

The application:

When detecting conflicts of interest (one of the main reasons that good leaders make bad decisions), coaches may take a less judgmental road to alerting leaders to this by pointing out that the decision-making centers in the brain usually stop all action in dealing with conflicting information and that the leader would benefit from facing this conflict so that there is more conscious control of the outcome. Here, coaches can also integrate the science of “hot reasoning” when leaders insist that they can separate out these kinds of conflicts by pointing out that brain research shows that emotional input is commonplace, even in deductive logic, and that the brain cannot truly be as objective as we think it can be. Similarly, leaders or managers themselves may communicate with people who report to them using the same principles.

6. The leader is attached to people, places, and things that are affecting his or her decisions

The concept:

When leaders become attached to people, places, or things, decision-making is affected.

25

Humans are reluctant to let go of their attachments, but in businesses, leaders who cannot access this flexibility in thinking can make poor decisions. Being attached is a complex phenomenon that can impact the brain in various ways (see

Chapter 3

, “The Neuroscience of Social Intelligence: Guiding Leaders and Managers to Effective Relationships,” for details). One important way is that attachment engages the reward system in the brain, and when people are rewarded, they may not be open to other rewards. As

a result, they are stuck in the same old patterns. When leaders are attached to old ideas, they are being served by these ideas, and this activates the reward center in the brain. If a new plan involves giving up these attachments (old computer systems, organizational hierarchy), the reward center in the brain “complains” and stops activating. As a result, the leader may feel as though he or she is on the wrong path. In addition to leaders forming attachments, companies also have attachments and often strive for a state of congruence between the different parts through their attachments.

26

The application:

When coaches are coaching leaders, it may help to remind leaders that there are two reward centers that need to be acknowledged: the reward center in the leader’s brain and the reward center in the organization’s brain. When a leader questions a path because something “does not feel right,” a coach may ask the leader whose reward system is talking: the leader’s or the organization’s?

7. The leader has misleading memories

The concept:

When leaders’ decisions are affected by misleading memories, this can have a powerful impact on a company.

25

The way in which we remember things often feels certain, even when it is incorrect. Forgetting things that just happened is common when short-term memory is overloaded or when anxiety disrupts DLPFC functioning. Thus, vital memories of what just happened may be lost. An easy-to-relate-to idea here is dieting. People often forget about sticking to diets or an exercise regime when they are anxious or they receive too much information. Also, studies show that the right hemisphere of the brain is involved when we generate false memories that we may be convinced are actually true.

27

Furthermore, when we are confident about our memories, these memories may either be true or false.

28

When they are true, the medial temporal lobe is activated; when they are false, the fronto-parietal cortex is activated. The higher our confidence, the more these regions will activate based on whether we are truly remembering past events or falsely remembering them.

The application

: Because misleading memories are one of the main reasons that good leaders make bad decisions, it is important to have language to describe that (1) false recollections are possible, even in highly intelligent people, and that (2) confidence does not always correlate with accuracy of memory. When coaches are looking to work with leaders who are high in confidence, they may let leaders know that confidence itself impacts the brain differently depending on whether the things that leaders are remembering are true or false. Even when memories are false, the brain can produce a sense of confidence, but for true and false memories, confidence impacts the brain in different brain regions. This will be helpful in alerting leaders to verify what they think they remember regardless of how confident they are.

8. The leader falls into a psychological trap

The concept:

Leaders may fall into one of many psychological traps.

29

For example, leaders may overemphasize recent events in a decision (anchoring trap), think that they are changing when they really are not because they lack sufficient flexibility in thinking and action (status quo trap), be overly cautious or prudent (prudence trap), or be trapped within a certain frame of thinking (framing trap). For each of these traps, there are biological correlates that relate: for the anchoring trap, short-term memory is involved but long-term memory is left out; for the status-quo trap, the brain region for flexibility in thinking needs to be exercised; for the prudence trap, the amygdala is overactivated; and for the framing trap, the ACC is stagnant and needs to be reengaged.

The application:

Coaches can justify approaches in coaching by using these biological substrates in the language of describing the traps. For example, coaches may say, “We need to involve short- and long-term memory in this reflection,” or “I would like to ask you some open-ended questions to encourage thinking flexibility,” or “Your brain’s fear detector may be applying the brakes on your strategy too much,” or “Your brain’s framing center is stuck, and we have coaching

interventions that can help it become unstuck.” Each of these language excerpts is just one of many examples of how the language of brain science can add to a coaching intervention.

This then outlines some of the assumptions that leaders may make about decisions and how brain science can help coaches undo these assumptions. Remember that although I am using the term “coaches” here, these principles apply equally to when the manager or leader has to act as a coach or communicator.

Table 1.2

summarizes these assumptions and how coaches can use the difference that brain science can make in our understanding to dispel with these assumptions.

Table 1.2. The Brain Science Behind Common Leadership Errors

A Map of Where the Book Is Going and What the Coach Will Take Away from It

Coaching involves establishing a reliable alliance with the client so as to create a context for change. Although the eventual goal is change, this change has to occur within the context of relationships. Brain science underlies both the relationships and actions necessary to create and maintain the change. The book is therefore broadly divided into the parts shown in

Figure 1.4

.

Figure 1.4. Structural outline of

Your Brain and Business: The Neuroscience of Great Leaders