1492: The Year Our World Began (24 page)

Read 1492: The Year Our World Began Online

Authors: Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

On January 15, he encountered a fair wind for home. Curiously, he began by setting a course to the southeast, but he quickly reverted to what had surely always been his plan: heading north, combing the ocean in search of the westerlies familiar to him from his early experiences of Atlantic navigation. All went fairly well until February 14, when he ran into a terrible storm, which provoked the first of a long series of intense religious experiences that recurred at every major crisis of Columbus’s life. He expressed a sense of divine election so intense that nowadays it would be regarded as evidence of suspect sanity. God had spared him for divine purposes; he had saved him from the enemies who surrounded him; “and there were many other things of great wonder which God had performed in him and through him.”

14

After taking refuge in the Azores he arrived home, congratulating himself on a miraculous deliverance, via Lisbon. There he had three interviews with the king of Portugal—a curious incident that has aroused suspicions of his intentions. Martín Pinzón, from whom the storm had parted him, arrived at almost the same time, exhausted by the exertions of the voy

age. He died before being able to present a report to the monarchs. Columbus had the field to himself.

Opinion was divided on Columbus’s achievement. One court cosmographer called it a “journey more divine than human.” But few other commentators endorsed Columbus’s opinions. Columbus had to insist he had reached or approached Asia: his promised rewards from the monarchs depended on his delivering on his promises in that respect. In the opinion of most experts, however, he clearly could not have reached Asia, or gotten anywhere near it: the world was too big for that. Most likely, Columbus had just encountered more Atlantic islands, like the Canaries. He might have stumbled on “the Antipodes”—an opinion many humanist geographers entertained with glee. “Lift up your hearts!” wrote one of them, “Oh, happy deed! That under the patronage of my king and queen the disclosure has begun of what was hidden from the first creation of the world!”

15

As it turned out, this was close to the truth: there really was a formerly unknown hemisphere out there. On a subsequent voyage, Columbus realized that he had indeed found what he called “another world.” But his contract with the monarchs was linked to his promise of a short route to Asia, and he was obliged to insist he had delivered on that promise, in order to claim his rewards. The explorers who followed up his voyages later in the decade proved that his route led to a vast area of continuous land without any of the characteristics, peoples, or products Europeans expected to find in Asia. But they went on looking for a westward route to the East. Maps of the sixteenth century generally underestimated the breadth both of the Americas and of the Pacific Ocean. Only very gradually in the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries did their true dimensions emerge.

Most of the gifts Columbus brought home had a certain exotic allure—captive natives, parrots, specimens of previously unknown flora—but no obvious exploitability. He did, however, have a small quantity of gold obtained from the natives by trade. And he claimed to have got near

to its source. That alone made a return voyage worthwhile from the monarchs’ point of view. He departed on September 24, 1493.

Columbus’s course this time led sharply south of his former track to Dominica in the Lesser Antilles, along what proved to be the shortest and swiftest route across the Atlantic. Once he was back in the Caribbean, his picture of his discoveries crumbled. First, the stories of cannibals proved gruesomely true when the explorers stumbled on the makings of a cannibal feast on the island Columbus named Guadalupe. Then, more grisly still, he found on arrival on Hispaniola that the natives had massacred the garrison he left there; so much for the innocuous, malleable “Indians.” Then, as he struggled to build a settlement, the climate proved deadly. What Columbus had praised as ideally salubrious turned out to be unbearably humid. His men grew first restive, then rebellious. There were reports—or were they later embellishments?—of ghostly wailings by night and of shadowy processions of headless men grimly greeting the famished colonists in the streets.

The disappointments masked a stunning achievement. Between them, Columbus’s ocean crossings of 1492–93 established the most practical and most exploitable routes back and forth across the Atlantic, linking the densely populated belt of the Old World, which stretched from China cross southern and southwestern Asia to span the Mediterranean, with the threshold of the richest and most populous regions of the New World.

Other explorers rushed to exploit the opening. In consequence, the 1490s were a breakthrough decade in Europe’s efforts to reach out across the ocean to the rest of the world. In 1496 another Italian adventurer, backed by merchants in Bristol and the English crown, discovered a direct route across the North Atlantic, using variable springtime winds to get across and the westerlies to get back: his route, however, was imperfectly reliable and remained little developed, except for access to the cod fisheries of Newfoundland, for over a hundred years. Meanwhile, Portuguese missions to the Indian Ocean by traditional routes investigated whether that ocean was genuinely landlocked. In 1497–98,

a Portuguese trading venture, commissioned by the crown and probably financed by Florentine bankers, attempted to use the westerlies of the South Atlantic to reach the Indian Ocean. Its leader, Vasco da Gama, turned east too early and had to struggle around the Cape of Good Hope. But he managed to get across the Indian Ocean anyway and reach the pepper-rich port of Calicut. The next voyage, in 1500, used the direct route without a serious hitch. Meanwhile, despairing of Columbus’s increasingly erratic behavior, Ferdinand and Isabella repudiated his monopoly and opened Atlantic navigation to his rivals. In 1498 Columbus effectively demonstrated the continental nature of his discoveries; before the decade was over, follow-up voyages by competitors confirmed the fact and traced the coastline of the New World from the narrows of the Central American isthmus to well south of the equator—probably at least to about thirty-five degrees south.

This breakthrough of the 1490s, which opened direct, long-range routes of maritime trade across the world between Europe, Asia, and Africa, seems sudden; but it is intelligible against the background of the slow developments in European technology and knowledge, and the acceleration of the benefits of Atlantic exploration in the previous decade. Was there more to it than that? European historians have long sought to explain it by appealing to something special about Europe—something Europeans had that others lacked, which would explain why the world-girdling routes, which linked the Old World to the New and the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic, were discovered by European enterprise and not by that of explorers from other cultures.

Technology is inescapably an area to search. It would, for instance, have been impossible for explorers to remain long at sea or return home from unfamiliar destinations without improved water casks and suitable navigational techniques. Most of the technical aids of the period, however, seem hopelessly inadequate to these tasks. Navigators relied on the sheer accumulation of practical craftsmanship and lore to guide them in unknown waters. Columbus’s failure with the quadrant and astrolabe suggests a further conclusion: if such technology had been

decisive, Chinese, Muslim, and Indian seafarers, who had access to similar tools centuries earlier, would have got farther faster than any of their counterparts from Europe.

The shipwright’s was a numinous craft, sanctified by the sacred images with which ships were associated: the ark of salvation, the storm-tossed bark, and the ship of fools. In partial consequence, it was a traditional business, in which innovation was slow. Little by little, during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, Atlantic and Mediterranean schools of shipbuilding exchanged methods of hull construction. Atlantic and northern shipwrights built for heavy seas. Durability was their main criterion. Characteristically, they built their hulls plank by plank, laying planks to overlap along their entire length and then fitting them together with nails. Mediterranean shipbuilders preferred to begin with the frame of the ship. Planks were then nailed to it and laid edge to edge. The Mediterranean method was the more economical. It demanded less wood and far fewer nails: once the frame was built, most of the rest of the work could be entrusted to less-specialized labor. Frame-first construction therefore spread all over Europe until by the sixteenth century it was the normal method everywhere. For ships expected to bear hard pounding, however, in wars or extreme seas, it remained worthwhile investing in the robust effect of overlapping planks.

The ships that carried the early explorers of the Atlantic were round-hulled and square-sailed—good for sailing with the wind, and therefore for tracing the routes outward from Iberia with the northeast trades and back via the Azores with the westerlies of the North Atlantic. Gradual improvements in maneuverability helped, as a result of tiny incremental improvements in rigging. In the fifteenth century, ships with at least one triangular sail appeared in the African Atlantic with increasing frequency—and sometimes with two or three, suspended on long yards attached by ropes to masts raked at an acute angle to the deck. These craft, usually called caravels, could sail close to the wind, tacking within much narrower confines than a conventional vessel when trying to beat their way across the path of the trade winds without being forced

too far to the south: typically, caravels could maintain a course only thirty degrees off the wind. They were useful along the African coast but made no contribution to transatlantic sailing. Columbus scrapped the triangular rig of one of his ships in favor of the traditional square sails.

If technology cannot explain what happened, then most of the cultural features commonly adduced remain unhelpful, either because they were not unique to the western European seaboard, because they are phony, or because they were not around at the right time. The political culture of a competitive state system was shared with Southeast Asia and with parts of Europe that contributed nothing to exploration. The explorers of the modern world operated among expanding states and emulous competitors in every continent. Christianity was less conducive to commerce than Islam or Judaism, among other religions that value the merchant life as a means to virtue. The tradition of scientific curiosity and empirical method was at least as strong in Islam and China in what we think of as the late Middle Ages (though it is true that a distinctive scientific culture did become discernible later in Europe and in the parts of the Americas settled from Europe). Missionary zeal is a widespread vice or virtue, and—though most of our histories ignore the fact—Islam and Buddhism both experienced extraordinary expansion into new territories and among new congregations, at the same time as Christianity, in what we think of as the late Middle Ages and early modern period. Imperialism and aggression are not exclusively white vices. We have seen evidence of only one feature of European culture that did make the region peculiarly conducive to breeding explorers. They were steeped in the idealization of adventure. Many of them shared or strove to embody the great aristocratic ethos of their day—the “code” of chivalry. Their ships were gaily caparisoned steeds, and they rode the waves like jennets.

The Atlantic breakthrough is part of a huge phenomenon: “the rise of the West,” “the European miracle”—the elevation of Western societies to paramountcy in the modern history of the world. Thanks to the displacement of traditional concentrations of power and sources of

initiative, the former centers, such as China, India, and parts of Islam, became peripheral, and the former peripheries, in western Europe and the New World, became central. Yet Europeans’ leap into global maritime prominence was not, it seems, the outcome of European superiority, but of others’ indifference and the withdrawal of potential competitors from the field. The Ottoman seaborne effort was stunning by the standards of the day. But straits stoppered it in every direction. In the central Mediterranean, the Persian Gulf, and the Red Sea, access to the oceans was through narrow channels easily controlled by enemies.

In other parts of the world to which we must now turn, opportunities were limited or neglected. Russia—overwhelmingly and inevitably in the face of an icebound ocean, despite the heroism of monks who colonized islands in the White Sea in the fifteenth century—was focused on expanding to landward. Chinese naval activity was aborted in the fifteenth century, probably as a result of the triumph at court of Confucian mandarins, who hated imperialism and despised trade. Civilizations in most other parts of the world had reached the limits of seaborne travel with the technology at their disposal, or were pinioned by winds or penned by their own diffidence. To understand Europe’s opportunity, we have to explore potentially rival regions. We can start by following Columbus’s imaginary trajectory, to China and the world of the Indian Ocean, and see what was happening there in and around 1492.

Jen-tzu—fifteenth day of the seventh month: Shen Zhou

paints a mystical experience.

U

sually, when he could not sleep, the painter lit his lamp and read. But reading could never bring rest to his mind. One summer’s night in 1492, he fell asleep to the sound of the rain. Suddenly, a cold gust nipped him into wakefulness.

The rain had ceased. He rose and dressed and spread a book, as usual, under the flickering candlelight. But he was too tired to read. So he just sat there in unrelieved silence, under an almost lightless moon, with the shutters drawn back to let in the rain-freshened air. Squatting on a low bench, he spent the rest of the night gazing vaguely into the darkness of the narrow courtyard of his house. He sat, as he recalled the next morning, “calmly doing nothing.”

Gradually, he began to notice sounds. Wind breathed somewhere in clumps of faintly rustling bamboo. Occasionally, dogs growled. The watchmen’s drumbeats marked the passage of hours. As the night lifted

and faint daylight spread, the painter heard a distant bell. He became aware of senses he usually repressed, and of little life-enhancing experiences you cannot find in books. He began to get from the world the insights he strove to convey in painting: true perceptions, which penetrate appearances and reach the heart and nature of things. All sounds and colors seemed new to him.

“They strike the ear and eye all at once,” he said, “lucidly, wonderfully, becoming a part of me.”

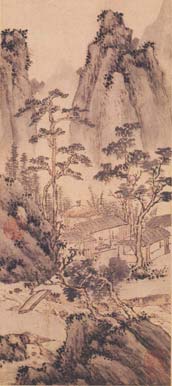

Not only did he make a written record of the experience. He also painted it, in ink and colors, on a scroll of paper designed to be weighted and hung on a wall. The painting survives. In the center of the composition, the painter is a tiny, hunched figure, wrapped in a thin robe, with a knot of hair gathered on his balding head. His low-burned light is beginning to get smoky on the table beside him. All around, the hazy light of dawn discloses immensities of nature that dwarf the painter and his flimsy house. Tall, great-rooted trees reach up, craggy cliffs rise, with mountains bristling in the background. But all their power seems to flow into the little man in the middle, without disturbing his tranquillity.

When he finished the scroll, he signed it with his name: Shen Zhou. He was sixty-five years old, and one of China’s most celebrated painters. Because he was rich in his own right, he was almost uniquely privileged among the painters of the world in his day. He could resist the lures of patrons, and paint what he wanted.

1

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, another individual with mystical inclinations, and a habit of staying up late at night, was struggling to imagine what China was like. Christopher Columbus was on his way there. At least, that was what he hoped. Or at least, that was what he said.

While Shen Zhou strove for calm and meditated in serenity, Columbus could not resist restlessness and operated in a violent and unstable part of the world. Readers of the last chapter will recall his story. Poor but ambitious, of modest means and few prospects, he had tried every

available means of escape into a world of wealth and grandeur: he had tried enlisting in war; he had thought of embracing a career in the Church; he had striven unsuccessfully to accumulate a fortune as a small-time merchant, shipping sugar and gum around the Mediterranean and the eastern Atlantic. We have seen how he had married—lovelessly, it seems—a minor aristocrat’s daughter, without achieving much social elevation as a result. He had modeled his life on fiction,

trying to live like the hero of the fifteenth-century equivalent of a dime novel—a seaborne tale of chivalric romance.

Shen Zhou recorded his nocturnal vigil in this sketch, in which he portrays himself dwarfed by nature, as well as a long prose account.

Detail from Shen Zhou,

Night Vigil

. Hanging scroll, National Museum, Taipei.

At last, in the attempt to get someone rich to back him to undertake a voyage of discovery, he hit on the idea of proposing a shortcut to China, westward, across the ocean, “where,” he said, “as far as we know for certain, no one has ever gone.” Doubts tortured him. No one knew how far away China was, but Europe’s geographers were almost united in the knowledge that the world was too big to be easily encompassed by the feeble ships available at the time, with their limited means of stowing fresh food and water. China was so far away, consensus averred, that Columbus and his crew, if they ever got there, would be dead on arrival. For an escapee from failure and poverty, though, the risk seemed worth taking. The bankers in Seville—Spain’s Atlantic-side boomtown—who backed Columbus did not have to risk much. And if he pulled off the feat he promised, the profits might be dazzling.

One of the inspirers of Columbus’s enterprise, the Florentine geographer Paolo Toscanelli, had pointed out the possibilities: “[T]he number of seagoing merchants in China is so great that in a single noble port city they outnumber all the other merchants of the world…. Westerners should seek a route there, not only because great wealth awaits us from its gold and silver, and all sorts of gems, and spices such as we never obtain, but also for the sake of China’s learned sages, philosophers, and skilled astrologers.”

2

Europeans did not know much about China, but they knew it was the biggest, richest market, the most productive economy, and the most powerful empire in the world. Beyond that, their detailed information was all out-of-date. Until about a hundred years before, contact with China had been fairly extensive. Merchants and missionaries shuttled back and forth along the Silk Roads that crossed the mountains and deserts of central Asia, spreading commodities and ideas through the continent and the world. For a while, in the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, it had even been possible to take a fast-track route on horseback across the Eurasian steppe—the great, arid, windswept prai

rie that arcs from the Hungarian plain, almost without interruption, across Mongolia to the Gobi and the threshold of China. Mongol imperialists united the entire route, conquered China, policed the Silk Roads, and facilitated communications throughout the breadth of the lands they ruled.

But in 1368 a revolution in China expelled the heirs of the Mongols and ruptured the roads. The last recorded European mission to China had made its way through in 1390. Since then, silence had enshrouded the distant empire. The only detailed description still available in Europe was even more antiquated—compiled toward the end of the thirteenth century by Marco Polo. As we have seen, Columbus and his contemporaries still thought of the emperor of China as the Great Khan—a Mongol title no Chinese ruler had borne since the revolution of 1368. Much as they longed for Chinese goods, they knew virtually nothing—yet—of porcelain or tea, the Chinese exports that would transform European taste in succeeding centuries.

They were right, however, about one thing: contact with China could provide unprecedented opportunities for Europeans to get rich. Ever since Roman times, Europeans had longed to break into the world’s wealthiest arena of exchange but had always labored under apparently insuperable disadvantages. Even when they could get to China, or to the other fabulously opulent markets around the Indian Ocean and on the shores of maritime Asia, they had nothing to sell. Their remote, peripheral corner of Eurasia was too poor. As a fourteenth-century Italian guide to the China trade complained, European merchants bound for China had to take silver with them—at the risk of impoverishing Europe further by draining bullion eastward—because the Chinese would accept nothing else. At the frontier, they had to hand the silver over to imperial customs officials and accept paper money in exchange. This, for the backward Europeans, was a novelty that demanded explanation and reassurance.

By the fifteenth century, although Europeans did not yet know it, changes in the economic situation in China, and in East Asia generally,

were creating new opportunities, for silver was rising spectacularly in value in China relative to other Asian markets as people’s confidence in paper and copper currency wavered. Anyone who could shift silver from India and Japan, where it was relative cheap, to China, where it could be exchanged for gold or goods on favorable terms, stood to make a fortune. If Europeans could get their ships to Eastern ports, they could profit from the differentials.

These new circumstances created conditions in which the history of the world could unfold in new, unprecedented ways. Columbus’s scheme for reaching China was part of a potentially world-transforming outreach that would, eventually, put the economies of East and West in touch and integrate them into a single, global system. Access to Eastern markets would unlock riches Westerners had formerly only dreamed of and enable them to begin to catch up with the richer economies and more powerful states that, previously, had dominated the world.

Columbus, however, never made it to China. On his first voyage, he stumbled on Caribbean islands where he warped the locals’ name, “Caniba,” into “people of the khan” and fantasized about his presumed proximity to the Orient. When he got home, engravers illustrated his reports of the poor, naked people he encountered with pictures of Chinese traders doing business offshore. When Columbus returned in 1493, he sailed around part of Cuba and made his crew swear that it was no island but a promontory of the Chinese mainland. On subsequent voyages, though he realized he was in “another world,” he continued to hope that China was nearby—through an undiscovered strait, or around some cape that lay just beyond his reach.

If he had got to his objective, what would he have found?

China was the nearest thing to a global superpower the world then knew: bigger and richer than all its possible competitors combined. The disparity of population was decisive. The statistics accumulated at the time were fragmentary and delusive, as millions of people successfully concealed themselves from the state in order to avoid taxes and forced

labor. China had the most sophisticated census-making methods in the world, but the figure of less than sixty million people reported by the empire’s statisticians in 1491 is certainly a serious underestimate. China had perhaps one hundred million people, whereas the whole of Europe mustered only about half that number. The size of the market and the scale of production matched the level of population. China’s giant economy dwarfed that of every other state in the world. The empire’s huge surplus of wealth distorted the economies of all the lands that looked to China to generate trade, from Europe, across Asia and the Indian Ocean, to Japan. China produced so much of everything that there was little demand for imported goods. The luxuries China did import, however, especially spices, aromatics, silver, and (more problematically) the warhorses of which China could never get enough, commanded prices that left buyers from elsewhere in the world marginalized.

A snapshot view of China at the time is available—but not, of course, from Western sources. A Korean official shipwrecked on the Chinese coast in 1488, and detained in the country while state officials investigated his status, wrote up his experiences and observations. Contemporaries in Korea disbelieved his account, which he was obliged to defend at court in 1492. His education in the Confucian classics and admiration for Chinese culture certainly influenced him. Still, the diary Ch’oe Pu compiled on his long journey by canal from the coast to the capital, and back to Korea by road, is a unique and vivid record by a keen observer, describing—as a sixteenth-century editor put it—“the ever-changing ocean, mountains, rivers, products, people, and customs all along the way.”

3

The Chinese, he found, recognized Korea as “a land of protocol and morality”

4

—a land like theirs, producing people they could deal with. But the unfamiliarity of strangers evoked surprise and suspicion. In almost every encounter Ch’oe Pu had, his hosts began by thinking evil of him: he was, they assumed, a Japanese pirate or a foreign spy. At times during his struggles to prove his identity, “it would

have been easier to die at sea.”

5

He clearly did not speak Chinese, but he made himself understood by writing everything down in the characters the Korean language had borrowed from China. Even learned interlocutors found his strangeness puzzling. “Why,” asked one of them in a typical conversation, “when your carriages have the same axle-width and your books the same writings as those of China, is your speech not the same?”

6

Even so, Ch’oe Pu was disposed to admire China and found plenty to justify his admiration. He encountered robbers mild enough to return his saddle. When he displayed his certificates, officials showed due respect for the high place he had attained in Korea’s civil-service examinations.

7

As his party trekked northward from the remote spot on the Chekiang coast where his ship came to grief, Chinese officials hustled and hurried them along with extraordinary efficiency, even a touch of officiousness. In eight sedan chairs at first, and then by boat along China’s great network of rivers and canals, with a military escort, they struggled through, regardless of weather. “The laws of China are strict,” the guard commander told Ch’oe Pu, who wanted to halt in the teeth of a storm. “If there is the slightest delay, we will be punished”—and he was right. When they arrived at Hangchow, after less than a fortnight on the road and with only one day’s rest, his zeal was rewarded with a flogging for having made poor time. It was unjust, but it was law. In China, laws served as deterrents, to fulfill a Confucian principle: punishments should be so severely deterrent that they need never be enforced.