1492: The Year Our World Began (28 page)

Read 1492: The Year Our World Began Online

Authors: Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

His life seems a series of evasions. He had an impressive array of virtues: in selecting artists he showed unerring judgment. In organizing poetry competitions he displayed unstinting industry. In identifying the problems of government he showed considerable sagacity. But he turned away from every disagreeable task: curbing his wife’s avarice,

reprimanding his son’s prodigality, punishing the warlords’ presumptions. He simply ignored the wars that broke out around him, withdrawing first into a circle of artistic mutual admiration in the capital, then resigning government responsibilities altogether in his country retreat before taking the final step: ordination as a Zen monk.

His profligacy probably helped cause the dissolution of the state by ratcheting up taxation, immiserating peasants, and leaving the central government bereft of an armed force. But at least it can be said to his credit that much of his spending was on the arts. While in power, he was a compulsive builder and redecorator of palaces. When he retired from public life, his hillside villa became like the country retreats of the Medici—a center where artists and literati gathered to perform plays, coin poems, practice the tea ceremony, blend perfumes, paint, and converse. Sometimes, warlords took time out from strife or state building on their own account in nearby provinces to join the soirees. Yoshimasa built a supposedly silver-foil-clad pavilion on the grounds, decorated with “rare plants and curious rocks,”

39

begun in 1482 and completed three years after his death, in 1493. To meet the costs, the government requisitioned labor from the dwindling number of loyal landowners in the provinces. In retirement, Yoshimasa boosted his income by engaging in trade in his own right, sending horses, swords, sulfur, screens, and fans to China and getting cash and books in return.

40

This shows both that a merchant life was no derogation, even for a former shogun, and that the troubles did not interrupt the trade.

In some ways, the arts of the time seem strangely indifferent to the wars. Kano Masanobu painted Chinese rivers and Buddhist worthies on the walls in styles derived from Chinese models. The critics and painters Shinkei Geiami and his son Soami coaxed great work from the brushes of pupils, such as the dynamic Kenko Shokei. But art was ultimately inseparable from the politics of the wars, because warlords paid for so much of it, and the shogun’s patronage was by no means disinterested.

One suspects that Yoshimasa employed artists because, at least in part, they were cheaper than warriors and more effective as mediators of

propaganda. Patronage of Noh theater, for instance, was traditional in the shogunal house, exhibiting heroic themes and aligning the shoguns with exemplars from a sometimes mythic past; it was while watching a play that Yoshimasa’s father had been assassinated. Because Yoshimasa had to maintain links around the kingdom, he commanded a brisk trade in portraits for distribution to provincial shrines, where they could focus loyalties, like fragments or relics of himself.

41

But Yoshimasa elevated art to a new rank as the Japanese equivalent of the “rites and music” Confucius had prescribed as essential to the health of the Chinese state.

42

Not everyone succumbed to Yoshimasa’s patronage. The painter of landscape in ink Toyo Sesshu visited China in 1467, after years of copying Chinese paintings. He served only provincial houses and declined to paint for Yoshimasa with a characteristically Chinese excuse: it was not right for a mere priest to paint in a “golden palace.”

43

Such dissent or fastidiousness was rare. Yoshimasa’s taste inspired swathes of the elite and of merchants who sought to spend their way to status. Provincial chieftains imitated his practice, inviting poets, painters, and scholars to elevate their own courts with learning and art. A once-popular theory about the origins of the Italian Renaissance ascribed investment in culture to the mood of hard times: when wars curtail opportunities to make money from trade, capitalists sink their money into works of art. Something of the sort seems to have happened in Japan in the long years of civil war from the late 1460s. The fear—often realized—that frequent burnings in the capital would destroy valuable libraries inspired a feverish enthusiasm for copying manuscripts. The flight of sages and artists from the capital helped spread metropolitan tastes around the country. Warlords competed for the services of poets and painters.

44

Yamaguchi, for instance, became a “little Kyoto,” graced by the presence of famous artists.

Shinkei’s wanderings are a case in point. In 1468 he left the capital for the east, to use his prestige as a Buddhist sage in the interests of one of the contending parties in the civil wars. He spent most of the next

four years responding to invitations from nobles to conduct poetical soirees in their castles and camps, endeavoring, he said, “to soften the hearts of warriors and rude folk and teach the way of human sensibility for all the distant ages.”

45

Spring afflicted him: “Even the flowers are thickets of upturned blades.”

46

Tranquillity, sorrow, and reflection in the midst of civil wars: Sogi, composing verses with fellow literati by a colleague’s grave under the full moon.

Nishikawa Sukenobu,

Ehon Yamato Hiji

(10 vols.; Osaka, 1742).

The adventures of another renowned poet exemplify the predicament of artists in a time of civil war. Sogi, an equally famous poet, usually traveled between provincial courts in response to invitations from aspiring patrons. In 1492, however, he stayed in the capital, educating aristocrats on the classics of the Heian era of nearly half a millennium before. He was seventy-three years old, and his taste for traveling was waning. In the summer of that year, however, he made an excursion into the countryside to visit Yukawa Masaharu, a minor warlord with literary ambitions. The sequence of poems he wrote for this patron begins with a prayer for the endurance of the house, likening Masaharu’s offspring to a

stand of young pines: “[Y]et still more tall may they grow.” But “the law,” he also wrote, “is not what it was.”

47

Piety was past.

Who will hear it?

The temple bell from the hills,

Off in the distance.

Despite Sogi’s prayers for him to be spared in the battle he had to face, Masaharu backed the wrong side in the conflict. Within a year of Sogi’s visit, his fortunes were in ruins. He disappeared from records after 1493.

Amazingly, this renaissance flourished in conditions of insecurity that might have paralyzed the city of Kyoto, where there were never enough loyal soldiers to keep order among the rival gangs who infested the city and the rival armies of warlords who often invested it. After the warlords’ armies withdrew from the wreckage in 1477, marauders took over. Full-scale warfare continued in the east of the country.

As war intensified, Japan dissolved into warring states. A self-made, self-appointed leader who came to be known as Hoso Soun demonstrated the opportunities. Having made his reputation in the service of other warlords, he struck out on his own, attracting followers by his prowess. In 1492 he conquered the peninsula of Izu and turned it into a base from which he proposed to extend his rule over the entire country. In 1494 he secured control of the peninsula by capturing the fortress of Odiwara, which commanded the approach to Izu, by posing as the leader of a party of deer hunters. He was never strong enough to get much farther than the neighboring province of Sagami, but his career was typical of the era, in which scores of new warlords burst onto the scene, established new dynasties, and set up what were in effect small independent states. At the same time, peasant communities organized their own armed forces, sometimes in collaboration with warlords.

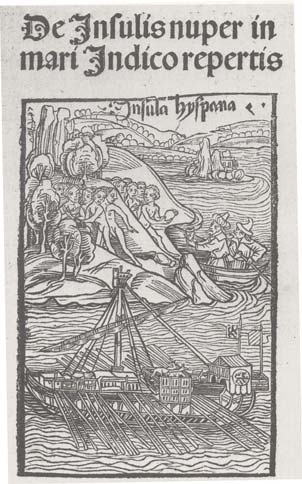

One of the earliest editions of Columbus’s first report shows the oriental merchants he expected to find trading with the natives of Hispaniola.

De Insulis Nuper in Mari Indico Repertis

(Basle, 1494).

Though China withdrew from imperial ambitions, and Japan, crumbling into political ineffectiveness, had not yet embarked on them, the underlying strength of those countries’ economies remained robust, and the vibrancy and dynamism of cultural life were spectacular.

Elsewhere, in widely separated parts of the world, to which we must now turn, expansion unrolled like springs uncoiling. An age of expansion really did begin, but the phenomenon was of an expanding world, not, as some historians say, of European expansion. The world did not simply wait passively for European outreach to transform it as if touched by a magic wand. Other societies were already working magic of their own, turning states into empires and cultures into civilizations. Some of the most dynamic and rapidly expanding societies of the fifteenth century were in the Americas, southwest and northern Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. Indeed, in terms of territorial expansion and military effectiveness against opponents, some African and American empires outclassed any state in western Europe.

The Indian Ocean, which China forbore to control—“the seas of milk and butter,” as ancient Indian legends called the seas that lapped maritime Asia—linked the world’s richest economies and carried the world’s richest commerce. It constituted a self-contained zone, united by monsoonal winds and isolated from the rest of the world by zones of storms and untraversable distances. For the future of the history of the planet, the big question was who—if anyone—would control the routes of commerce now that the Chinese had withdrawn. In the 1490s, that issue was unresolved. But the Indian Ocean was also an arena of intense, transmutative cultural exchange, with consequences that the world is still experiencing, and to which we must now turn.

January 19: Nur ad-Din Abd ar-Rahman Jami dies

at Herat.

C

onventional historiography suffers from too much hot air and not enough wind. For the whole of the age of sail—that is, almost the whole of the recorded past—winds and currents set the limits of what was possible in long-range communications and cultural exchange. Most would-be explorers have preferred to sail into the wind, presumably because, whether or not they made any discoveries, they wanted to get home. Phoenicians and Greeks, for instance—dwellers at the eastern end of the Mediterranean—explored the length of that sea, working against the prevailing wind. In the Pacific, Polynesians colonized the archipelagoes of the South Seas, from Fiji to Easter Island, by the same method.

Generally, however, fixed wind systems inhibit exploration. Where winds are constant, there is no incentive to try to exploit them as causeways to new worlds. Either they blow into one’s face, in which case

seafarers will never get far under sail, or they sing at one’s back—in which case they will prevent venturers from ever returning home. Monsoon systems, by contrast, where prevailing winds are seasonal, encourage long-range seafaring and speculative voyages, because navigators know that the wind, wherever it bears them, will eventually turn and take them home.

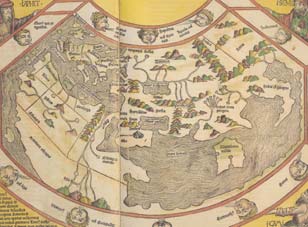

The world map of the Nuremberg Chronicle illustrates the suspicion, derived from Ptolemy, that the Indian Ocean was landlocked.

Nuremberg Chronicle.

It depresses me to think of my own ancestors, in my family’s homeland in northwestern Spain, staring out unenterprisingly at the Atlantic for hundreds, perhaps thousands of years, and never troubling to go far out to sea—dabbling, at most, in fishery and coastal cabotage. But the winds pinioned them, like butterflies in a collector’s case. They could scarcely have imagined what it feels like, sensing the wind, year in, year out, alternately in one’s face and at one’s back. That is what happens on the shores of maritime Asia, where the monsoon dominates the environment. Above the equator, northeasterlies prevail in winter. When winter ends, the direction of the winds is reversed. For most of the rest

of the year they blow steadily from the south and west, sucked in toward the Asian landmass as air warms and rises over the continent.

By timing voyages to take advantage of the predictable changes in the direction of the wind, navigators could set sail, confident of a fair wind out and a fair wind home. In the Indian Ocean, moreover, compared with other navigable seas, the reliability of the monsoon season offered the advantage of a speedy passage in both directions. To judge from such ancient and medieval records as survive, a trans-Mediterranean journey from east to west, against the wind, would take fifty to seventy days. With the monsoon, a ship could cross the entire Indian Ocean, between Palembang in Sumatra and the Persian Gulf, in less time. Three to four weeks in either direction sufficed to get between India and a Persian Gulf port.

In 1417 a Persian ambassador heading for India did it in even less time. Abd er-Razzaq was bound for the southern Indian realm of Vijayanagar. There were too many hostile states in the way for him to go by land. His ship sailed late, in the terrifying, tempestuous spell of weather toward the end of summer, when the caustic heat of the Asian interior drags the ocean air inward with ferocious urgency. The merchants who were to have accompanied the ambassador abandoned the voyage, crying “with one voice that the time for navigation was past, and that everyone who put to sea at this season was alone responsible for his death.” Fright and seasickness incapacitated Abd er-Razzaq for three days. “My heart was crushed like glass,” he complained, “and my soul became weary of life.” But his sufferings were rewarded. His ship reached Calicut, the famed pepper emporium on the Malabar coast, after only eighteen days’ sailing from Ormuz.

1

The Indian Ocean has many hazards. Storms rend it, especially in the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and the deadly belt of habitually bad weather that stretches across the ocean below about ten degrees south. The ancient tales of Sinbad are full of shipwrecks. But the predictability of a homebound wind made this the world’s most benign environment for long-range voyaging for centuries—perhaps millennia—before the

continuous history of Atlantic or Pacific crossings began. The monsoon liberated navigators in the Indian Ocean and made maritime Asia the home of the world’s richest economies and most spectacular states. That is what attracted Europeans—Asia’s poor neighbors—eastward, and why Columbus and so many of his predecessors, contemporaries, and successors sought a navigable route to what they called the Indies.

In the fifteenth century, the biggest single source of influence for change in the region was the growing global demand for, and therefore supply of, spices and aromatics—especially pepper. No one has ever satisfactorily explained the reasons for this increase. China dominated the market and accounted for well over half the global consumption, but Europe, Persia, and the Ottoman world were all absorbing ever greater amounts. Population growth contributed—but the increase in demand for spices seems greatly to have exceeded it. As we saw in chapter 1, the idea that cooks used spices to mask the flavor of bad meat is nonsense. Produce was far fresher in the medieval world, on average, than in modern urbanized and industrialized societies, and reliable preserving methods were available for what was not consumed fresh. Changing taste has been alleged, but there is no evidence of that: it was the abiding taste for powerful flavors—a taste now being revived as Mexican, Indian, and Szechuan cuisines go global—that made spices desirable. The spice boom was part of an ill-understood upturn in economic conditions across Eurasia. In China, especially, increased prosperity made expensive condiments more widely accessible as the turbulence that brought the Ming to power subsided and the empire settled down to a long period of relative peace and internal stability.

In partial consequence, spice production expanded into new areas. Pepper, traditionally produced on India’s Malabar coast, and cinnamon, once largely confined to Sri Lanka, spread around Southeast Asia. Pepper became a major product of Malaya and Sumatra in the fifteenth century. Camphor, sappanwood and sandalwood, benzoin and cloves all

overspilled their traditional places of supply. Nonetheless, enough local specialization remained within the region to ensure huge profits for traders and shippers; and the main markets outside Southeast Asia continued to grow.

For that brief spell early in the fifteenth century, in the reign of the Yongle emperor, when Chinese navies patrolled the Indian ocean, it looked as if China might try to control trade and even production in spices by force. The emperor exhibited an impressive appetite for conquest. Perhaps because he was a usurper with a lot to prove, he was willing to pay almost any price for glory. From the time he seized the throne in 1402 until his death twenty-two years later, he waged almost incessant war on China’s borders, especially on the Mongol and Annamese fronts. He scattered at least seventy-two missions to every accessible land beyond China’s borders. He sent silver to the shogun in Japan (who already had plenty of silver), and statues of Buddha and gifts of gems and silks to Tibet and Nepal. He exchanged ill-tempered embassies with Muslim potentates in central Asia. He invested kings in Korea, Melaka, Borneo, Sulu, Sumatra, and Ceylon. These far-flung contacts probably cost more in gifts than they raised in what the Chinese called “tribute”: live okapis from Bengal, white elephants from Cambodia, horses and concubines from Korea, turtles and white monkeys from Siam, paintings from Afghanistan, sulfur and spears and samurai armor from Japan. But they were magnificent occasions of display, which gave Yongle prestige in his own court and perhaps some sense of security.

2

The grandest and most expensive of the missions went by sea. Between 1405 and 1433 seven formidable flag-waving expeditions ranged the Indian Ocean under Admiral Zheng He. As we have seen, the scale of his efforts was massive, but their cultural consequences were, in many ways, more pervasive than their political impact. The voyages lasted, on average, two years each. They visited at least thirty-two countries around the rim of the ocean. The first three voyages, between 1405 and 1411, went only as far as the Malabar coast, the principal source of the world’s pepper supply, with excursions along the coasts of

Siam, Malaya, Java, Sumatra, and Sri Lanka. On the fourth voyage, from 1413 to 1415, ships visited the Maldives, Ormuz, and Jiddah, and collected envoys from nineteen countries.

Even more than the arrival of the ambassadors, the inclusion of a giraffe among the tribute Zheng He gathered caused a sensation when the fleet returned home. No one in China had ever seen such a creature. Zheng He acquired his in Bengal, where it had arrived as a curiosity for a princely collection as a result of trading links across the Indian Ocean. Chinese courtiers instantly identified the creature as divine in origin. According to an eyewitness, it had “the body of a deer and the tail of an ox and a fleshy boneless horn, with luminous spots like a red or purple mist. It walks in stately fashion and in its every motion it observes a rhythm.” Carried away by confusion with the mythical

qilin

or unicorn, the same observer declared, “Its harmonious voice sounds like a bell or musical tube.”

The giraffe brought assurances of divine benevolence. Shen Du, an artist who made a living drawing from life, wrote verses to describe the giraffe’s reception at court:

The ministers and the people all gathered to gaze at it and their joy knows no end. I, your servant, have heard that when a sage possesses the virtue of the utmost benevolence, so that he illuminates the darkest places, then a qilin appears. This shows that your Majesty’s virtue equals that of heaven. Its merciful blessings have spread far and wide, so that its harmonious vapours have emanated a ch’ilin, as an endless blessing to the state for myriad years.

3

Accompanying the visiting envoys home on a fifth voyage, which lasted from 1416 to 1419, Zheng He collected a prodigious array of exotic beasts for the imperial menagerie: lions, leopards, camels, ostriches, zebras, rhinoceroses, antelopes, and giraffes, as well as a mysterious beast, the

Touou-yu

. Drawings made this last creature resemble a white tiger with black spots, while written accounts describe a “righteous

beast” who would not tread on growing grass, was strictly vegetarian, and appeared “only under a prince of perfect benevolence and sincerity.” There were also many “strange birds.” An inscription recorded: “All of them craned their necks and looked on with pleasure, stamping their feet, scared and startled.” That was a description not of the birds but of the enraptured courtiers. Truly, it seemed to Shen Du, “all the creatures that spell good fortune arrive.”

4

In 1421, a sixth voyage departed with the reconnaissance of the east coast of Africa as its main objective, visiting, among other destinations, Mogadishu, Mombasa, Malindi, Zanzibar, and Kilwa. After an interval, probably caused by changes in the balance of court factions after the death of the Yongle emperor in 1424, the seventh voyage, from 1431 to 1433, renewed contacts with the Arabian and African states Zheng He had already visited.

5

Mutual astonishment was the result of contacts on a previously unimagined scale. In the preface to his own book about the voyages, Ma Huan, an interpreter aboard Zheng He’s fleet, recalled that as a young man, when he had contemplated the seasons, climates, landscapes, and people of distant lands, he had asked himself in great surprise, “How can such dissimilarities exist in the world?”

6

His own travels with the eunuch-admiral convinced him that the reality was even stranger. The arrival of Chinese junks at Middle Eastern ports with cargoes of precious exotica caused a sensation. A chronicler at the Egyptian court described the excitement provoked by news of the arrival of the junks off Aden and of the Chinese fleet’s intention to reach the nearest permitted anchorage to Mecca.

After that, there were no more such voyages. Part, at least, of the context of the decision to abort Zheng He’s missions is clear. The examination system and the gradual discontinuation of other forms of recruitment for public service had serious implications. Scholars and gentlemen reestablished their monopoly of government, with their indifference toward expansion and their contempt for trade. In the 1420s and 1430s the balance of power at court shifted in the bureaucrats’ favor, away from the Buddhists, eunuchs, Muslims, and merchants who

had supported Zheng He. When the Hongxi emperor ascended the throne in 1424, one of his first acts was to cancel Zheng He’s next voyage. He restored Confucian officeholders, whom his predecessor had dismissed, and curtailed the power of other factions. In 1429 the shipbuilding budget was cut almost to extinction. China’s land frontiers were becoming insecure as Mongol power revived. China needed to turn away from the sea and toward the new threat.

7

The consequences for the history of the world were profound. Chinese overseas expansion was confined to unofficial migration and, in large part, to clandestine trade, with little or no imperial encouragement or protection. This did not stifle Chinese colonization or commerce. On the contrary, China remained the world’s most dynamic trading economy and the world’s most prolific source of overseas settlers. Officially, “not a plank floated” overseas from China. In practice, prohibitions had only a modest effect. From the fifteenth century onward, Chinese colonists in Southeast Asia made vital contributions to the economies of every place they settled; their remittances home played a big part in the enrichment of China. The tonnage of shipping frequenting Chinese ports in the same period probably equaled or exceeded that of the rest of the world put together. But, except in respect of islands close to China, the state’s hostility to maritime expansion never abated for as long as the empire lasted. China never built up the sort of wide-ranging global empire that Atlantic seaboard nations acquired. An observer of the world in the fifteenth century would surely have forecast that the Chinese would precede all other peoples in the discovery of world-girdling, transoceanic routes and the inauguration of far-flung seaborne imperialism. Yet nothing of the sort materialized, and the field remained open for the far less promising explorers of Europe to open up the ways around the world.