1492: The Year Our World Began (32 page)

Read 1492: The Year Our World Began Online

Authors: Felipe Fernandez-Armesto

His acknowledged masterpiece was his immensely long last poem,

Yusuf and Zulaikha,

a searing love story that encodes a religion of Jami’s devising, which, without any overt tampering with Islam, is utterly personal, and takes stunning liberties with the Quran. He takes the Quranic story of Yusuf—the biblical Joseph—and the seductress he encountered in his flight from his abusive brethren, and turns it into a treatise on love as a sort of ladder of Bethel—a means of ascent to personal union with God. The author begins by addressing readers who seek mystical experience. “Go away and fall in love,” he counsels. “Then come back and ask me.” Loving union is a way of connecting with God, “who quickens the heart and fills the soul with rapture.” Zulaikha first sees her future lover in a vision so powerful that lust impedes her from loving him truly. While the world goggles at his splendor and beauty, his wife tortures herself with reproaches and longs for death. If she had grasped the inward form instead of embracing the body that conceals it, she would have found that conjugal love can be a means of ascent to God.

She begins to glimpse the truths of mysticism—the possibilities of self-realization through self-immersion in love, but carnality obstructs

her. Jami says, “As long as love has not attained perfection, lovers’ sole preoccupation is to satisfy desire…. They willingly prick the beloved with a hundred thorns.” Zulaikha has to go through a series of terrible purgations, which are like the classic stages of mystical ascent: despair, renunciation, blindness, oblivion. She endures repeated rejection by Yusuf and loses everything that once mattered to her—her wealth, her beauty, and her sight—before the lovers can be united. Zulaikha perceives the mystic truth:

In solitude, where Being signless dwelt,

And all the universe still dormant lay

Concealed in selflessness, One Being was

Exempt from “I” or “Thou”-ness, and apart

From all duality; Beauty Supreme,

Unmanifest, except unto Itself

By Its own light, yet fraught with power to charm

The souls of all; concealed in the Unseen,

An Essence pure, unstained by aught of ill.

41

Carnal love shatters like a graven idol. Yusuf’s real beauty strikes his inamorata afresh, like a light so dazzling that he seems lost in it.

From Everlasting Beauty, which emerged

From realms of purity to shine upon

The worlds, and all the souls which dwell therein.

One gleam fell from It on the universe

And on the angels, and this single ray

Dazzled the angels, till their senses whirled

Like the revolving sky. In diverse forms

Each mirror showed it forth, and everywhere

Its praise was chanted in new harmonies.

The cherubim, enraptured, sought for songs

Of praise. The spirits who explore the depths

Of boundless seas, wherein the heavens swim

Like some small boat, cried with one mighty voice,

“Praise to the Lord of all the universe!”

42

Nowadays, most people, I suspect, will find it hard to think of mysticism as modern. It was, at least, a gateway to one of the great mansions of modernity: the enhanced sense of self—the individualism, sometimes edging narcissism or egotism, that elbows community to the edge of our priorities. Without the rise of individualism, it would be hard to imagine a world organized economically for “enlightened self-interest” or politically along lines of “one person, one vote.” Modern novels of self-discovery, modern psychology, feel-good values, existential angst, and the self-obsessions of the “me generation” would all be unthinkable. Liberation from self-abnegation had to begin—or at least have one of its starting points—in religious minds, because godly institutions, in the Middle Ages, were the major obstacles to self-realization. The watchfulness of fellow congregants disciplined desire. The collective pursuit of salvation diminished individuals’ power. The authority of godly establishments overrode individual judgment. Mysticism was a way out of these constraints. For worshippers with a hotline to God, institutional religion is unnecessary. Sufis, Catholic and Orthodox mystics, and Protestant reformers were all, therefore, engaged, in one sense, in the same project: firing the synapses that linked them to divine energy; freeing themselves to make up their own minds; putting clerisy in its place. Whatever modernity is, the high valuation of the individual is part of it. The mystics’ role in making modernity has been overlooked, but by teaching us to be aware of our individual selves, they helped to make us modern.

March 6: A young Montezuma celebrates

tlacaxipehualiztli,

the spring fertility festival, and

witnesses the sacrifice of human captives—their hearts

ripped out, their bodies rolled down the high temple steps.

I

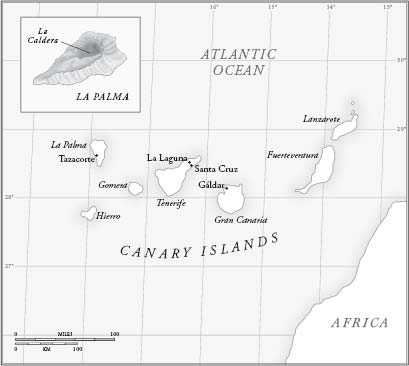

n 1493, when Columbus got back from his first voyage, no one—least of all the explorer himself—knew where he had been. In the received picture of the planet, the earth was an island, divided between three continents: Europe, Asia, and Africa. For most European scholars, it was hard to believe that what they called “a fourth part of the world” existed. (Some Native American peoples, by coincidence, called the earth they trod “the fourth world”—to distinguish it from the heavens, the waters, and the underground darkness.) Humanist geographers, who knew ancient writers’ speculations that an “antipodean” continent awaited discovery, groped toward the right conclusion about what Columbus had found. Others assumed—more consistently with the evidence—that he had simply stumbled on “another Canary

Island”: another bit of an archipelago that Spanish conquistadores were already struggling to incorporate into the dominions of the crown of Castile. This was a pardonable error: Columbus’s newfound lands were on the latitude of the Canaries. Their inhabitants, by Columbus’s own account, were “like the Canary Islanders” in color and culture. Despite Columbus’s urgent search for valuable trade goods, the new lands seemed, even to the discoverer, more likely to be viable as sources of slaves and locations for sugar-planting—just as the Canaries had been.

Guamán Poma’s early-seventeenth-century drawing of work on a rope bridge under the supervision of the Inca inspector of bridges, whose ear-spools denote his elite status.

F. Guamán Poma de Ayala,

Nueva coró nica y buen gobierno (codex pé ruvien illustré)

(Paris: Institut d’Ethnologie, 1936).

The conquest of the Canary Islands was a vital part of the context of Columbus. The archipelago was a laboratory for conquests in the Americas: an Atlantic frontier, inhabited by culturally baffling strangers, who seemed “savage” to European beholders; a new environment, uneasily adaptable to European ways of life; a land that could be planted

with new crops, exploited with a new, plantation-style economy, settled with colonists, and wrenched into new, widening patterns of trade.

In the Canaries, the conquest of the Atlantic world was already under way when Columbus set sail. The core of the financial circle that paid for his first transatlantic voyage formed when a consortium of Sevillan bankers and royal treasury officials combined to meet the costs of conquering Grand Canary in 1478–83. Columbus’s point of departure was the westernmost port of the archipelago, San Sebastián de la Gomera, which became fully secure only when a Spanish army uprooted the last native resistance on that island in 1489. The Spaniards did not reckon the conquest of the most intractable islands as complete until 1496.

The natives—all of whom disappeared in the colonial era owing to conquest, enslavement, disease, and assimilation—were among the last descendants of the pre-Berber inhabitants of North Africa. For a sense of what they were like, the nearest surviving parallels are the Imraguen and Znaga—the poor, marginal fishing folk who cling to the coastal rim of the Sahara today, surviving only by occupying places no one else wants. Along with the advantages of isolation, the islanders enjoyed—before Europeans arrived—a mixed economy, based on pastoralism supplemented by farming cereals in small plots, from which they made

gofio

—slops of powdered, toasted grain mixed with milk or soup or water that are still eaten everywhere in the islands but appreciated, as far as I know, nowhere else. They made a virtue of isolation, abandoning navigation and barely communicating from island to island, even though some islands lie within sight of one another—rather like the ancient Tasmanians or Chatham Islanders or Easter Islanders, who imposed isolation on themselves. They forswore the technology that took them to their homes, as if they were consciously withdrawing from the world, like dropouts of a bygone era. Insulation from the rest of the world, however, has disadvantages. Contact with other cultures stimulates what we call development, whereas isolation leads to stagnation. The material culture of the Canarians was rudimentary. They lived in

caves or crudely extemporized huts. They were armed, when they had to face European invaders, only with sticks and stones.

The ferocity and long-sustained success of their resistance gives the lie to the notion that superior European technology guaranteed rapid success against “primitives” and “savages.” Adventurous European individuals and ambitious European states launched expeditions at intervals from the 1330s. They depleted some islands by enslaving captives, but they could not establish any enduring presence until a systematic effort in the early fifteenth century, launched by adventurers from Normandy, secured control of the poorest and least-populated islands of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, and Hierro. The conquerors installed precarious but lasting colonies, which, after some hesitation and oscillation between the crowns of France, Portugal, and Aragon, ended owing allegiance to Castile.

After that, the conquest stalled again. The remaining islands repelled many expeditions from Portugal and Castile. In the mid–fifteenth century, the Peraza family—minor noblemen of Seville who had acquired the lordship of some islands, and claimed the right of conquest over the rest—gained a footing in Gomera, where they built a fort and exacted tribute from the natives, without introducing European colonists. Repeated rebellions culminated in 1488, when the natives put the incumbent lord, Hernán Peraza, to death, and the Spanish crown had to send an army to restore order. In revenge, the insurgents were executed or enslaved in droves, with dubious legality, as “rebels against their natural lord.” The Spaniards put a permanent garrison on the island. The treatment of the natives, meanwhile, touched tender consciences in Castile. The monarchs commissioned jurists and theologians to inquire into the case. The inquiry recommended the release of the slaves, and many of them eventually returned to the archipelago to help colonize other islands. Their native land, however, was now ripe for transformation. In the next decade, European investors turned it over to sugar production.

Ferdinand and Isabella, who were not yet committed to the exhausting effort of conquering Granada, thought intervention worthwhile be

cause of Castile’s rivalry with Portugal, which made the Canaries seem important. Castilian interlopers in the African Atlantic had long attracted Portuguese complaints, but the war of 1474–79, in which Afonso V of Portugal challenged Ferdinand and Isabella for the Castilian throne, intensified Castilian activity. The monarchs were openhanded with licenses for voyages of piracy or carriage of contraband. Genoese merchant houses with branches in Seville and Cadiz and an eye on the potential sugar business were keen to invest in these enterprises. The main action of the war took place on land, in northern Castile, but a “small war” at sea in the latitude of the Canaries accompanied it. Castilian privateers broke into Portugal’s monopoly of trade and slaving on the Guinea coast. Portuguese attacks menaced Castilian outposts in the Canary Islands. The value of the unconquered islands of

the archipelago—Grand Canary, Tenerife, and La Palma, which were the largest and most promising economically—became obvious. When Ferdinand and Isabella sent a force to resume the conquest in 1478, a Portuguese expedition in seven caravels was already on its way. The Castilian intervention was a preemptive strike.

The Canary Islands.

Other, longer-maturing reasons also influenced the royal decision. First, the monarchs had other rivals than the Portuguese to keep in mind. The Perazas’ lordship had descended by marriage to Diego de Herrera, a minor nobleman of Seville, who fancied himself as a conquistador. His claim to have made vassals of nine native “kings” or chiefs of Tenerife and two on Grand Canary was, to say the least, exaggerated. He raided the islands in the hope of extracting tribute by terror, and attempted, in the manner of previous would-be conquistadores, to dominate them by erecting intimidating turrets. Such large, populous, and indomitable islands, however, would not succumb to the private enterprise of a provincial hidalgo. Effective conquest and systematic exploitation demanded concentrated resources and heavy investment. These were more readily available at the royal court.

Even had Herrera been able to complete the conquest, it would have been unwise for the monarchs to let him do so. He was not above intrigue with the Portuguese, and he was typical of the truculent paladins whose power in peripheral regions was an affront to the crown. Almost since the first conquerors seized power in the Canaries, lords and kings had been in dispute over the limits of royal authority in the islands. Profiting from a local rebellion against seigneurial authority in 1475–76—one of a series of such rebellions—Ferdinand and Isabella decided to enforce their suzerainty and, in particular, the most important element in it: the right to be the ultimate court of appeal throughout the colonies of the archipelago. In November 1476 they launched an inquiry into the legal basis of lordship in the Canaries. The results were enshrined in an agreement between seigneur and suzerain in October 1477: Herrera’s rights were unimpeachable, saving the superior lord

ship of the crown; but “for certain just and reasonable causes,” which were never specified, the right of conquest should revert to Ferdinand and Isabella.

Beyond the political reasons for intervening in the islands, there were economic motives. As always in the history of European meddling in the African Atlantic, gold was the spur. According to a privileged chronicler, King Ferdinand was interested in the Canaries because he wanted to open communications with “the mines of Ethiopia”

1

—a general name, at the time, for Africa. The Portuguese denied him access to the new gold sources on the underside of the African bulge, where the trading post of São Jorge da Mina opened in 1482. Their refusal must have stimulated the search for alternative sources and helps explain the emphasis Columbus’s journals placed on the need for gold. Meanwhile, the growth of demand for sugar and dyes in Europe made the Canaries worth conquering for their own sake: dyes were among the natural products of the archipelago; sugar was the boom industry European colonists introduced.

The conquest was almost as hard under royal auspices as under those of Diego de Herrera. Native resistance was partly responsible. Finance and manpower proved elusive. One of Ferdinand’s and Isabella’s chroniclers could hardly bring himself to mention the campaigns in the Canaries without complaining about the expense. Gradually, although the monarchs’ aims in arrogating the right of conquest included the desire to exclude private power from the islands and keep it in the “public” domain, they had to allow what would now be called “public-private partnerships” to play a role. Formerly the monarchs had financed the war by selling indulgences—documents bishops issued to penitents remitting the penalties their sins incurred in this world. Ferdinand and Isabella claimed and exercised the right to sell these to pay for wars against non-Christian enemies. But as the war dragged on and revenues fell, they made would-be conquerors find their own funds. Increasingly, instead of wages, conquistadores received pledges of conquered land. Instead of reinvesting the crown’s share of booty in further campaigns,

the monarchs granted away uncollected booty to conquerors who could raise finance elsewhere. By the end of the process, ad hoc companies financed the conquests of La Palma and Tenerife, with conquerors and their backers sharing the proceeds.

The islands—as a royal secretary remarked of Grand Canary—might have proved insuperable, but for internal divisions the Spaniards were able to exploit. For the first three years of the conquest of Grand Canary, the Castilians, undermanned and irregularly provisioned, contented themselves with making raids on native villages. Working for wages, and therefore with little incentive to acquire territory, the recruits from urban militia units did not touch the mountain fastnesses on which the Canarians used to fall back for defense. Rather, they concentrated on places in the low plains and hills, where food, not fighting, could be found—the plains where the natives grew their cereals, the hillsides up and down which they shunted their goats. It was a strategy of mere survival, not of victory. Between raids, the invaders remained in their stockade at Las Palmas, where inactivity bred insurrection.