A Dance with Death: Soviet Airwomen in World War II (45 page)

Read A Dance with Death: Soviet Airwomen in World War II Online

Authors: Anne Noggle

I was totally trusting of my crew with the exception of the mechanic; he had failed me once by not checking the fuel tanks, and

another time he didn't warm up the engines in the winter. Besides, he

was so dirty-mouthed I couldn't stand it. I was brought up with real

Russian intelligentsia who survived the socialist revolution in

Leningrad. My family lived in a roomy house, with six families and

eleven children in one apartment. Our parents treated us carefully. In

our big flat lived a novelist who read us poems and stories, and we

children sat near the fire and absorbed all those wonderful pieces of

literature. Her elder daughter played the piano and sang for us. All the

tenants of our flat added much to our upbringing. We never heard

rude words, shouts, or swearing. So back to the crew: no matter how

much the mechanic pleaded to be left in the crew, I replaced him. The

crew comprised a pilot, copilot, tail gunner, navigator, mechanic, and

radio operator.

We were transferred to a division of the long-distance flights,

closer to the front. After this redeployment, the commanding staff of

the division invited me to a division dinner with their major-general

at the head of table. As the dinner came to an end, I noticed that the

general's staff were quietly sneaking out of the room. I tried to follow

their example, but I was stopped by the commander of the division. I

understood that the general wanted to bed me down. Yes, I was only a

lieutenant, but apart from that I was Olga Lisikova, and it was impossible to bed me down. His pressure was persistent. I had to think very

fast, because he was in all respects stronger than me, and I knew well

that nobody would dare to come to my rescue. In desperation I said, "I

fly with my husband in my crew!" and he was taken aback. He didn't

expect to hear that. He released me; I immediately rushed out and

found the radio operator and mechanic of my crew. I didn't make

explanations. I, as commander of the crew, ordered that one of them

was to be my fictitious husband and gave them my word of honor that

nobody would ever learn the truth! Then I released them.

I couldn't sleep all night; I couldn't believe any commander would

behave like that. I thought, Were generals allowed to do anything that

came to mind? I couldn't justify his behavior. The only explanation

that seemed appropriate was that I was really very attractive in my

youth. Thank God we flew away early the next morning.

I already had 120 combat missions when our division began receiving the C-47 aircraft. It was a most sophisticated plane, beyond any

expectations. We pilots didn't even have to master it-it was perfect

and flew itself! Before I was assigned a mission in it, I made one check

flight. My next flight was a combat mission, to drop paratroopers to

liberate Kiev. Later, when Kiev had been liberated, I flew there again.

There were few planes on the landing strip, and in the distance I saw

an aircraft of unusual shape, like a cigar. I realized at once that it was

an American B-29. I taxied and parked next to it. My radio operator,

tail-gunner, and I were invited aboard by the American crew. We

spoke different languages, but my mechanic knew German and an

American spoke it also; thus, the communication took place. The

outside of the aircraft was no surprise, but when you got into it,

touched it, and saw the most sophisticated equipment, you realized

that it was the most perfect aircraft design. The Americans received

us very warmly. The news that we flew the American C-47 made

them respect us more. The most astonishing news for them was that

I, a woman, was commander of the plane. They couldn't believe it. It

was an instant reaction-I suggested that I would fly them in my plane to prove it! I put the crew in the navigator compartment and

placed the copilot in the right seat beside me. The flight was short,

six or seven minutes, but it was hilarious. After that I was strictly

reprimanded by my commander.

By the time I had made 200 combat missions, I was entrusted at

last to fly in the Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff of the

Red Army. I will tell you about one of those flights. I was assigned a

mission to drop six paratroopers into the deep rear of the enemy.

When we ascended to the altitude of 3,000 meters the tail-gunner

reported a Focke Wulf 19o on our tail, but not attacking. I couldn't

understand why; then decided that it was a reconnaissance aircraft,

and the pilot was interested in what cargo we carried. I knew if I

changed course or dove, he would start firing. I climbed up a little and

hid the aircraft in the clouds. The fascist instantly began attacking us

but made another mistake by firing while he was facing the moon,

which blinded him. There were bullets bouncing against the fuselage

but so far no serious damage. He attacked once more but with no

success, because we were by then deep in the clouds.

We had changed course, so now we corrected it and crossed the

front line. In the enemy rear we usually flew at a very low altitude,

because the Germans had detectors sensitive to flights above 300

meters. Our path to the enemy rear was a crooked route, because we

avoided flying over towns and other places where we might be detected. It happened that we flew directly over an enemy airfieldbombers were circling around it. I knew that these fields were surrounded by antiaircraft guns and sound detectors that could easily

tell we were Russian. More experienced pilots had told me to quickly

change the engine sound if this happened to me, so I ordered the

mechanic to change the synchronization of the engines so we might

sound like a German Junkers aircraft. It worked; we flew through the

area without an attack.

At last we arrived at the appointed spot, and my passengers bailed

out. We held to that course so the Germans couldn't identify the

place where the men jumped; then we took a course back to our base.

After about forty minutes at low altitude, the mechanic inquired if I

had touched the fuel-tank switch. I was angry, because in my crew we

had a strict rule: never interfere with other crew members' work. But

then he showed me the fuel-tank switch circling of its own accord. I

understood what had happened: the German fighter had shot the fuel

lines, and now we had fuel only in one tank, only enough for one and

one-half hours. The other fuel tanks had been cut off.

We chose the shortest route to the front line, but when the red

light began signaling that we were running out of fuel, goosebumps

ran back and forth over my body. I even felt dizzy at the very thought

that in a few moments we would crash. I continued flying in a desperate hope to cross back over the front line-and we did! At night the

terrain is clearly perceivable, and I decided to land the plane. At any

moment the engines could quit. I ordered the crew to go back to the

tail of the aircraft, but nobody moved. I throttled back and began

gliding down. I did not lower the landing gear, having decided to

belly-land. But at this moment, the lights of a landing strip lit up. The

mechanic managed to lower the gear, and we touched down. It turned

out to be a front-line airdrome for small planes. When the aircraft

stopped and we were to deplane, we saw that we were surrounded by

military carrying guns. I ordered the mechanic to open the door and

say a few phrases in both German and Russian. Then the misunderstanding was cleared up. The day before, a German bomber had

landed at that airdrome, and when he found that he had landed on

Russian territory, he very quickly took off again.

In another episode I was assigned a mission to fly to the enemy

rear and drop supplies to the partisans. I crossed the front line at

4,000 meters, and at the appointed place began a dive. The altimeter

showed me to be lower and lower, but I could see nothing through the

clouds. Finally the altitude read zero and then less than that. Judging

by the meter I was to be deep in the soil, but still I held the dive. I

couldn't return to base without completing my mission: I didn't want

to he reproached after the flight that I hadn't fulfilled the risky mission only because I was a coward, because I was a woman. Then I

glimpsed the ground, and below me was the target where we were to

drop the cargo. The area was covered with dense, patchy fog. We

dropped the supplies to the partisans and returned to base.

When we arrived we learned that all the crews had turned back,

not having managed to fulfill the mission. Everyone was astonished.

How could I, a woman, do what other male pilots hadn't managed to

accomplish? The division commander said he would promote me to

be awarded the Gold Star of Hero of the Soviet Union, but I never

received that award, because my crew consisted of males. If the crew

had been female, it would have been awarded.

I flew with that division almost the whole war and completed 280

combat missions, but I was never awarded a single order. Although I

was promoted for awards, it was always denied. The deputy commander of the division staff told me that it was totally his fault and responsibility that I had never been given an order. He had decided

that I might get a swelled head in the purely male division if I had

been given a high award. Instead, he thought it quite healthy for

stories about me to be published in the press. Twenty years later,

when I met him at the reunion of our division, I saw that his breast

was pinned with high awards. I told him that during the whole war I

had made more than 28o combat flights as commander of the aircraft,

while he had all the traces of distinction on his body although he

hadn't made a single combat flight.

I had a funny episode in 1945 when Kiev was liberated. I was assigned to pick up football players from Kiev and bring them to Moscow. I was sitting in the cockpit watching them approach the aircraft,

swaying and hardly moving their feet. No doubt they were drunk.

Their looks made me laugh until I heard dirty words-it enraged me.

They didn't know that the commander of the crew was a woman. I

decided to teach them a lesson. I climbed to 4,000 meters and totally

disconnected the passenger compartment from the heating system.

Some time later their coach entered the cockpit. I demanded an apology for their swearing; otherwise, I would freeze them to death. All

together they cried out, "Olga, forgive us." When we landed and I

passed by them, they stood with their heads bowed. I smiled, and

thus our friendship started.

Later, in 1945, I flew the same team to play a match with another

football team. In the airport where we landed they asked me to be

their guest and gave me a seat at the commentator's booth. I was

hurrying to my seat when I met a friend, a press correspondent, who

introduced me to a young man, Volf Plaksin by name. It was my fate; I

have lived in love with my second husband for forty-five happiest

years. Then, two years ago, he died.

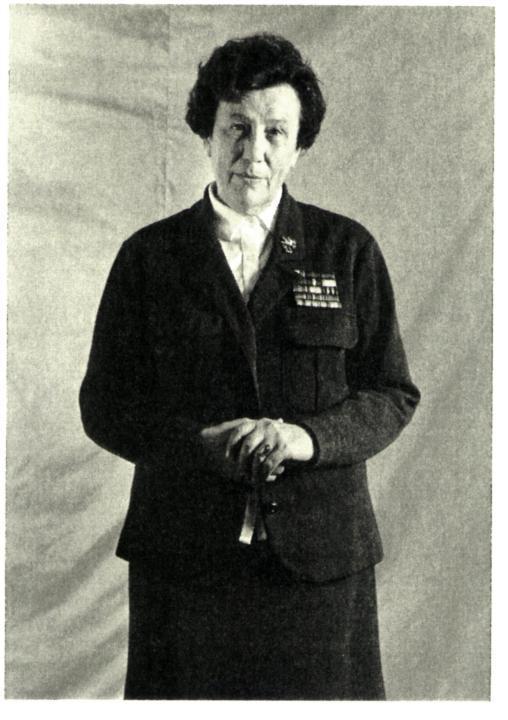

NOTE: Olga Lisikova, who lives in St. Petersburg, was not available

for an interview, and her reminiscences were obtained by correspondence. There is no present-day photograph of her.

I always keep in touch with my friends-it is

for the last day of my life.

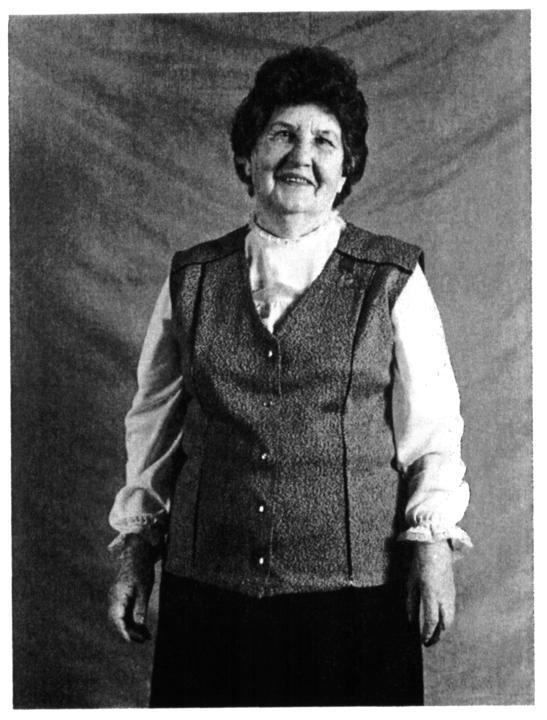

Nina Slovokhotova

586th Fighter Regiment

Nina Raspopova