A Dance with Death: Soviet Airwomen in World War II (41 page)

Read A Dance with Death: Soviet Airwomen in World War II Online

Authors: Anne Noggle

The last of my war experience is that I have more than one hundred sisters. We regularly meet twice a year in front of the Bolshoi

Theater on the second of May and the eighth of November. Outsiders

look, and they can't understand old ladies that sing and make noise.

Of course this war was a just war, and that is why we are proud of our

participation.

Introduction

Women not only flew in the three regiments organized by Marina

Raskova but in other diverse units of the Red Air Force. Anna

Timofeyeva-Yegorova, deputy commander of the 805th Ground Attack Regiment, was the only woman pilot in that organization. She

flew the powerful Illyushin Sturmovik.

Anna Popova flew with the Toth Guard Air Transport Division as a

flight radio operator on an Li-2 twin-engine transport aircraft.

Pilot Olga Lisikova, also in the Transport Division, later flew in

the Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff in C-47, lend-lease,

American transport aircraft.

A number of other women who were later transferred to one of the

women's regiments began the war in male units. Marina Raskova

attempted to gather all the women serving in the air force into her

regiments but was not entirely successful.

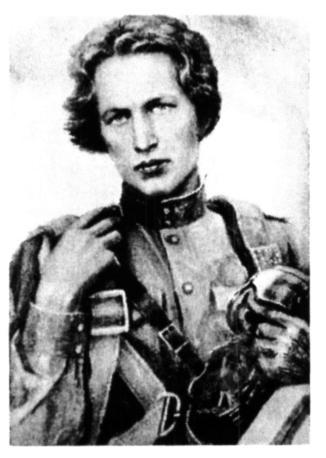

Senior Lieutenant Anna Timofeyeva-Yegorova,

pilot, deputy commander and navigator of the regiment

Hero of the Soviet Union

Xo5th Ground Attack Regiment

When the war ended I returned to college for a master's degree in

history and, later, another master of technical science degree at an

aviation technical college. My husband was a pilot and our division

commander during the war. He died ten years ago. I have two sons, and

one of them is an air force pilot. I never sleep when I know he is flying.

I was horn in 1918 in the town of Torzhok, between Moscow and

Leningrad. When my father died, my brother brought me here to

Moscow where he was working. I finished secondary school in Moscow, entered a trade school to become a locksmith, and then worked

on the metro construction. In those days either you quit the Kom somol or you went to work building the metro. The metro was considered to be the most gorgeous and fabulous creation of the century,

and all the young Komsomol members were expected to work on it.

While I was working, I also managed to complete some courses

called Rubfuk, or workers' faculty, a four-year course. I also attended

a glider school. When I finished that program I was transferred to the

powered-aircraft pilot school in Kherson, where I trained to became a

flight instructor, and then I taught cadets to fly. When the war broke

out in 1941 I volunteered to go to the front.

It was September, 1941, the month of my first combat mission. I

began flying the Po-2 aircraft with a male air regiment, making reconnaissance flights in the daytime. It was very dangerous to fly the Po-2

in daylight, because it was a slow, defenseless aircraft made of fabric,

which made it very vulnerable to enemy fire. The German fighters

often shot it down. My only armament was a pistol. The Germans

were given the highest order for shooting down and capturing Russian pilots if they remained alive.

In the spring of 1942 my plane was set on fire by the Germans,

and I managed to land the burning aircraft. We were given no parachutes at all. When I landed I jumped out of the cockpit and ran for

the woods, luckily in Soviet territory. While I was running the German fighters were firing at me from the air. I fell down several times

and again ran. There was a cornfield, and the stalks were still there

from the previous year. When I fell, I dug my head into the heap of

corn and lay there while they fired at me. The plane burned

completely.

I was on a mission to bring a secret, urgent message to the staff of

our Air Army. I had it with me and knew I had to somehow deliver

that message, so I started out on foot and ran. Our troops were

retreating, and the Germans were rapidly advancing. Here and there

I could see fascist tanks and infantry from a distance. Then I was

picked up by our troops and made my way toward headquarters. It

was difficult with all the troops and traffic on the road, so I combined walking and riding. I had burns on my hands and feet, especially on the knees, because I was dressed in a skirt and had suffered

the burns before I could land. Finally I delivered the message to

headquarters, and they bandaged my burns there and sent me back

to my squadron by truck.

I served in a squadron with staff headquarters on the southern

front. The dream of all the pilots in my squadron was to fly combat

and not to carry messages. We all wanted to fight back. Finally I was allowed to join a male regiment

where I could be trained as a

combat pilot. Later, I heard that

Raskova wanted me to join her

regiment. She sent six messages

requesting that I join, but the

staff did not even let me know

about it. Only after the war did I

find out.

Anna Timofeyeva-Yegorova,

805th Ground Attack Regiment

When I first started flying

the Illyushin Sturmovik 11-2

aircraft, it had one cockpit only.

Because we were shot down

very regularly, they added the

second cockpit in the fuselage

with a gunner facing to the rear

armed with a large-caliber machine gun. We usually flew at

an altitude of about eight hundred meters to drop bombs and

at a lower altitude of about four

hundred meters for attacking and strafing. Every pilot wanted to fly

the 11-2, because it was a heavy plane carrying 6oo kilos of bombs and

two machine guns and rockets. It was used as a close ground support

aircraft at the front lines against tanks, airdromes, railways, shipseverything.

I had a very strange reaction when I was flying over the target: my

lips would bleed. They were very dry and would bleed, but not from

biting them. In the summer of 1943, a third of the flying personnel in

the regiment were killed over the Black Sea. Over the sea we flew

very low, and even though the aircraft was well protected we suffered

heavy losses. During the war my heart sank when I was flying combat

missions over the sea; even now I am afraid of the sea. My regiment

was stationed on the coast, the coast of the Sea of Azov, and these

awful, frightful storms would develop over the sea.

The so-called Blue Line was a fortified area made by the Germans,

and it had been impossible to break through it. So they decided that

we should make a smoke screen to cover our troops while they

moved forward to penetrate these defenses. Before this operation, the

commander of our regiment lined us up and said that he needed

nineteen volunteers. Everyone volunteered. He selected commanders and deputy commanders of the squadrons, and he called my name.

This mission was by order of the commander of the front.

In the morning before the mission we lined up and handed in all

our documents to the staff. The planes were disarmed, and balloons

filled with gas were affixed instead. We were not to deviate from our

course, not to take any evasive action, and fly one after another. We

flew down the Blue Line, a distance of eleven kilometers. I was told to

count three seconds and then release the gas. We were fired on constantly; the front line was completely on fire. I wanted to look behind

to see what was happening but I couldn't, for I would then perhaps

have deviated from the course.

When we had fulfilled our mission and were returning to base, our

commander radioed that, thanks to God, we all were here and were

returning to the airdrome. Meanwhile, anyone who had damage to

their aircraft should land first. It was transmitted to us that all the

pilots who had completed the mission successfully had already been

awarded the Order of Red Banner. When we landed, got out of our

cockpits, and lined up, the commander of the army awarded us the

decoration right there.

Once, in the Taman region, I was to make a reconnaissance flight.

Our attack planes were usually protected by the fighter aircraft. The

fighters were stationed closer to the front line, and as I flew past the

airdrome I saw the two fighters that were to protect my plane taking

off. I transmitted to them that I was going to reconnoiter the ground

and photograph it and to please protect me. After my transmission I

heard, "Why are you speaking in such a tiny voice?" and "You are

called a fighter? You're not a fighter!" and several bad expressions

after that. I realized they didn't know I was a woman.

The flight was very successful; I managed to photograph the

front line even though they made some holes in the plane. I visually

reconnoitered the landscape; then I turned back with the two

fighters still protecting me. I reported from the air to my airdrome,

and the fighter pilots could hear the conversation. After I had reported, the person on the ground said, "Thank you, Anechka," and

only then did they realize I was a woman. They began circling

around and wagging their wings at me. We arrived over their airfield, and I told them, "Thank you, brothers; land, please." They did

not land at their airdrome but escorted me to my field, wagged their

wings again, and flew away. When I landed and came into the headquarters, they were all laughing and smiling at me, saying, "See,

Lieutenant Yegorova has found bridegrooms!" When at last we liber ated the Taman Peninsula in 1943, our regiment was transferred to

the First Belorussian Front.

It all happened on August 20, 1944, Aviation Day. The commander

promised to throw a party after we returned from our combat mission

(this was in Poland). By that time I was already the regimental navigator. Our troops had crossed the Vistula River; the Germans wanted to

eliminate this bridgehead, and they had sent in reinforcements of

tanks, artillery, and guns. Our mission was to stop this force. Half the

attack planes were led by the commander of the regiment, a force of

fifteen aircraft, and the other half were led by me, as deputy commander. The first group took off, and after an interval of ten minutes

my group followed. Ten fighters protected our fifteen planes. We proceeded to the area of the bridgehead. When I was making my first

pass, the antiaircraft guns started firing at my plane and hit it. The

pilots in my group saw that my plane was hit and that I did not have

complete control. They asked and even begged me on the radio to

turn back, but I didn't listen to reason. Now, so many years have

passed and I still don't know why I didn't listen to them, but I went

on and made the second pass over the target.

It was very difficult to be the leader of a male squadron. They trust

you-not because you are a woman, but because you are a skillful and

trained pilot. The Germans always fired at the lead plane, because if

the leader could be shot down, the formation would disperse and

leave without a commander. My aircraft became more uncontrollable; it was continuously going nose up. They fired at my plane with

great intensity, and my gunner-a woman-was killed. I saw the glass

dividing the two cockpits covered with her blood. The instrument

panel was smashed, and the engine was burning. The radio was damaged, and I had no communication. By then I had no vision of the

ground or the planes. I tried to open the canopy but it wouldn't open. I

became choked with the smoke and fire. The plane exploded; I was

blown out of the cockpit and lost consciousness.

When I opened my eyes, I was free of the aircraft and falling

through the air. I pulled the ring and the parachute opened, but not

completely. When I hit the ground I was falling very fast. I don't know

if I lost consciousness, but when I opened my eyes there was a fascist

standing over me with his boot on my chest. I was seriously injured: I

had a broken spine, head injuries, broken arms, and a broken leg. I

was burned on my knees, legs, and feet, and the skin was torn on my

neck. I remember the face of the fascist; I was very afraid that I would

be tortured or raped.

I remember very little of how I was carried to the fascist barracks,

but I was very much afraid of the Germans and the atrocities they

could inflict on me. My only wish was that I be shot, and the sooner

the better. I was brought initially to a fascist camp in Poland. I lay

motionless, and I was given water through a straw by the prisoners.

The Germans tore off the ribbons from my uniform. I heard Polish

speech but very little else. I recall that two Germans dressed in rubber aprons came up to me in the barracks, and they poured some

powder over my burns. I shouted and cried and screamed so loud that

the Polish imprisoned there thought I was being tortured. But it was

my injuries that made me cry out. I couldn't breathe because all my

ribs were broken.