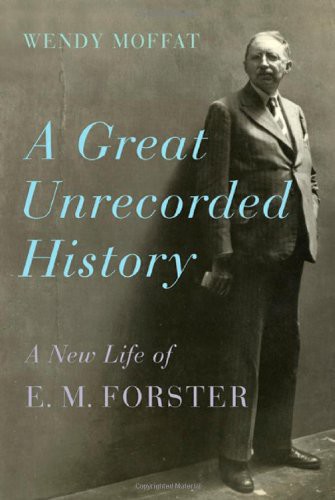

A Great Unrecorded History: A New Life of E. M. Forster

Read A Great Unrecorded History: A New Life of E. M. Forster Online

Authors: Wendy Moffat

Tags: #Biography, #British, #Literary

A Great Unrecorded History

A NEW LIFE OF E. M. FORSTER

Wendy Moffat

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

18 West 18th Street, New York 10011

Copyright © 2010 by Wendy Moffat

All rights reserved

Distributed in Canada by D&M Publishers, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2010

Owing to limitations of space, all acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published material appear on pages 405–408.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Moffat, Wendy, 1955–

A great unrecorded history : a new life of E. M. Forster / Wendy Moffat.—1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-374-16678-6

1. Forster, E. M. (Edward Morgan), 1879–1970. 2. Forster, E. M. (Edward Morgan), 1879–1970—Relations with men. 3. Forster, E. M. (Edward Morgan), 1879–1970—Friends and associates. 4. Authors, English—20th century—Biography. 5. Gay authors—Great Britain—Biography. I. Title.

PR6011.O58Z8228 2010

823'.912—dc22

[B]

2009029504

Designed by Jonathan D. Lippincott

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Donald,

who listened

,

and for Lucy and Emma

A Great Unrecorded History

That He Was Homosexual”

The wooden gate snapped shut behind him, and John Lehmann descended the steps carved into the canyon wall. Twenty feet below the road a small modern house nestled in the hillside. Entering the living room gave an uncanny feeling of going outdoors—the small house was bright and expansive, even on a misty November morning. Here at the north end of Santa Monica it was still possible to believe in the wildness and innocence of California. The room offered an extravagant, improbable view. Hardtop twisting below, a little house with a peaked Tudor roof almost hidden among the green of eucalyptus, live oak and pines, flat boxy roofs, down down down a cascade of curves and rectangles like a Cezanne landscape. Far off, a mirror image in the steep face of the opposite canyon. Over Lehmann’s left shoulder the gray glint of the Pacific Ocean shimmered in the mist. It was just before Thanksgiving 1970.

Christopher Isherwood had summoned him. He and Lehmann had been friends for almost forty years. They first met in the early 1930s, in the damp Bloomsbury office of Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press. Lehmann, then the Woolfs’ assistant, had persuaded them to publish Isherwood’s novel

The Memorial

. Isherwood and Lehmann made a striking pair—two gay British expatriates of distinctly opposite types. Small and still boyish though he was over sixty, Isherwood retained the seductive, irreverent charm that made it “impossible not to be drawn to him.” He had bright blue sparkling eyes, a flop of brown hair raked across his forehead, and a shelf of eyebrow that had grown wild and white with age. Lehmann was a different kind of attractive, a full head taller, leonine. He was three years younger than Isherwood, but seemed a generation older. Since his youth, he had projected an air of authority verging

on pomposity. His mane had gone gray before he was thirty, and he spoke slowly in a commanding, precise baritone that “might have belonged to a Foreign Office expert.”

Lehmann’s “pale narrowed quizzing eyes” had discovered most of the crop of young political writers who revolutionized writing in the thirties. He brought Brecht and García Lorca to British audiences. Stephen Spender and C. Day Lewis became household names because of Lehmann’s promotion of their work. Auden’s poem “Lay Your Sleeping Head My Love” and George Orwell’s essay “Shooting an Elephant” debuted in Lehmann’s anthology

New Writing

. And he nurtured Isherwood’s Berlin stories from

I Am a Camera

to

Cabaret

. He had done more than anyone alive to capture the vitality and range of the British writers born in the first years of the twentieth century.

But his sway had diminished. Lehmann had been a major force in publishing fiction and poetry, but the newest generation of angry writers were playwrights. Osborne, Pinter, and Orton owed nothing to Lehmann. Eventually even his eponymous imprint—once the arbiter of the best of the new—lost its cachet and the backing of the moneymen. When his publishing career collapsed, Lehmann turned to America by necessity. He began an itinerant life lecturing on campuses where he could hold forth on his long-lived and impressive literary connections. Each term, he embarked on a new tragic romance with a much younger American man who adored him for the few months it took for the patina to wear off. Despite living in Austin, San Diego, and Berkeley, he remained British to the core.

Christopher Isherwood had given up on England long ago. With his friend and sometime lover W. H. Auden he emigrated to America in January 1939. Isherwood, the man who held “the future of the English novel in his hands,” was excoriated for abandoning his country in time of war. Auden stayed in New York but Isherwood pressed westward, settling in Los Angeles, his “sexual homeland.” He became a U.S. citizen in 1946. For three decades he had been happily ensconced in Southern California. On the beach below—within sight of the canyon house—he had met the great love of his life, the young artist Don Bachardy. He and Bachardy had lived together for almost twenty years. But this afternoon he consulted the old friend who had known him forever, a friend from the old world. Though sometimes he found Lehmann’s self-importance boring, Christopher valued his editorial instinct. He had a secret, and he wanted John’s advice.

A packet had arrived from King’s College, Cambridge. In death, Morgan Forster had brought them together again. The great architect of narrative surprise had unveiled a final turn of plot.

E. M. Forster, the “master” whom they called by his intimate name, Morgan, was the only writer of the previous generation they admired without reservation. On the face of it, he seemed like an odd literary mentor. Born in 1879, Forster was more than twenty years their senior. He made his name before the First World War. By the time he was thirty, he had published a collection of short stories and four well-received novels:

Where Angels Fear to Tread

,

The Longest Journey

,

A Room with a View

, and

Howards End

. Compared to the great experimenters Joyce or Woolf, Forster’s early novels seemed sedate. But to John and Christopher, these subtle satires of buttoned-up English life were revelatory and unpredictable. Christopher admired Morgan’s light touch, his razor balance of humor and wryness, insight and idealism. “Instead of trying to screw all his scenes up to the highest possible pitch, he tones them down until they sound like mothers’-meeting gossip . . . There’s actually

less

emphasis laid on the big scenes than on the unimportant ones.” The novels looked at life from a complicated position—finding a dark vein of social comedy in the tragic blindness of British self-satisfaction. In spite of their sensitivity, they had a sinewy wit.