A House Divided (47 page)

Authors: Pearl S. Buck

And Yuan promised, doubting, too, it ever could be done. For who could say what days lay ahead? There was no more surety in these days—not even surety of the earth in which the Tiger must soon lie beside his father.

At this moment they heard a voice cry out, and it was the Tiger’s voice, and Yuan ran in and Mei-ling after him, and the old Tiger looked at them wildly and awake, and he said clearly, “Where is my sword?”

But he did not wait for answer. Before Yuan could say his promise over, the Tiger dropped his two eyes shut and slept again and spoke no more.

In the night Yuan rose from his chair where he watched and he felt very restless. He went first and laid his hand upon his father’s throat as he did every little while. Still the faint breath came and went weakly. It was a stout old heart, indeed. The souls were gone, but still the heart beat on, and it might beat so for hours more.

And then Yuan felt so restless he must go out for a little while, shut as he had been these three days within the earthen house. He would, he thought, steal out upon the threshing floor and breathe in the good cool air for a few minutes.

So he did, and in spite of every trouble pressing on him the air was good. He looked about upon the fields. These nearest fields were his by law, this house his when his father died, for so it had been apportioned in the old times after his grandfather died. Then he thought of what the old tenant had told him, how fierce the men upon the land were grown, and he remembered how even in those earlier days they had been hostile to him and held him foreign though he did not feel it then so sharp. There was nothing sure these days. He was afraid. In these new times who could say what was his own? He had nothing surely of his own except his own two hands, his brain, his heart to love—and that one whom he loved he could not call his own.

Even while he so thought, he heard his name called softly and he looked and there stood Mei-ling in the doorway. He went near her quickly and she said, “I thought he might be worse?”

“The pulse in his throat is weaker every time I feel it. I dread the dawn,” Yuan answered.

“I will not sleep now,” she said. “We will wait together.”

When she said this Yuan’s heart beat very hard once or twice, for it seemed to him he had never heard that word “together” so sweetly used. But he found nothing he could say. Instead he leaned against the earthen wall, while Mei-ling stood in the door, and they looked gravely across the moonlit fields. It was near the middle of the month, and the moon was very clear and round. Between them while they watched the silence gathered and grew too full to bear. At last Yuan felt his heart so hot and thick and drawn to this woman that he must say something usual and hear his voice speak and hers answer, lest he be foolish and put forth his hand to touch her who hated him. So he said, half stammering, “I am glad you came—you have so eased my old father.” To which she answered calmly, “I am glad to help. I wanted to come,” and she was as quiet as before. Then Yuan must speak again and now he said, keeping his voice low to suit the night, “Do you—would you be afraid to live in a lonely place like this? I used to think I would like it—when I was a boy, I mean—Now I don’t know—”

She looked about upon the shining fields and on the silvery thatch of the little hamlet and she said, thoughtfully, “I can live anywhere, I think, but it is better for such people as we are to live in the new city. I keep thinking about that new city. I want to see it. I want to work there—perhaps I’ll make a hospital there one day—add my life to its new life. We belong there—we new ones—we—”

She stopped, tangled in her speech, and then suddenly she laughed a little and Yuan heard the laughter and looked at her. In that one look they two forgot where they were and they forgot the old dying man and that the land was no more sure and they forgot everything except the look they shared. Then Yuan whispered, his eyes still caught to hers, “You said you hated me!”

And she said breathlessly, “I did hate you, Yuan—only for that moment—”

Her lips parted while she looked at him and still their eyes sank deeper into each other’s. Indeed, Yuan could not move his eyes until he saw her little tongue slip out delicately and touch her parted lips, and then his eyes did move to those lips. Suddenly he felt his own lips burn. Once a woman’s lips had touched his and made his heart sick. … But he wanted to touch this woman’s lips! Suddenly and clearly as he had never wanted anything, he wanted this one thing. He could think of nothing else except he must do this one thing. He bent forward quickly and put his lips on hers.

She stood straight and still and let him try her lips. This flesh was his—his own kind. … He drew away at last and looked at her. She looked back at him, smiling, but even in the moonlight he could see her cheeks flushed and her eyes shining.

Then she said, striving to be usual, “You are different in that long cotton robe. I am not used to see you so.”

For a moment he could not answer. He wondered that she could speak so like herself after the touch upon her, could stand so composed, her hands still clasped behind her as she stood. He said unsteadily, “You do not like it? I look a farmer—”

“I like it,” she said simply, and then considering him thoughtfully she said, “It becomes you—it looks more natural on you than the foreign clothes.”

“If you like,” he said fervently, “I will wear robes always.”

She shook her head, smiling again, and answered, “Not always—sometimes one, sometimes the other, as the occasion is—one cannot always be the same—”

Again somehow they fell to looking at each other, speechless. They had forgotten death wholly; for them there was no more death. But now he must speak, else how could he longer bear this full united look?

“That—that which I just did—it is a foreign custom—if you disliked—” he said, still looking at her, and he would have gone on to beg her forgiveness if she disliked it, and then he wondered if she knew he meant the kiss. But he could not say the word, and there he stopped, still looking at her.

Then quietly she said, “Not all foreign things are bad!” and suddenly she would not look at him. She hung her head down and looked at the ground, and now she was as shy as any old-fashioned maid could ever be. He saw her eyelids flutter once or twice upon her cheeks and for a moment she seemed wavering and about to turn away and leave him alone again.

Then she would not. She held herself bravely and she straightened her shoulders square and sure, and she lifted up her head and looked back to him steadfastly, smiling, waiting, and Yuan saw her so.

His heart began to mount and mount until his body was full of all his beating heart. He laughed into the night. What was it he had feared a little while ago?

“We two,” he said—“we two—we need not be afraid of anything.”

Pearl S. Buck (1892–1973) was a bestselling and Nobel Prize-winning author of fiction and nonfiction, celebrated by critics and readers alike for her groundbreaking depictions of rural life in China. Her renowned novel

The Good Earth

(1931) received the Pulitzer Prize and the William Dean Howells Medal. For her body of work, Buck was awarded the 1938 Nobel Prize in Literature—the first American woman to have won this honor.

Born in 1892 in Hillsboro, West Virginia, Buck spent much of the first forty years of her life in China. The daughter of Presbyterian missionaries based in Zhenjiang, she grew up speaking both English and the local Chinese dialect, and was sometimes referred to by her Chinese name, Sai Zhenzhju. Though she moved to the United States to attend Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, she returned to China afterwards to care for her ill mother. In 1917 she married her first husband, John Lossing Buck. The couple moved to a small town in Anhui Province, later relocating to Nanking, where they lived for thirteen years.

Buck began writing in the 1920s, and published her first novel,

East Wind: West Wind

in 1930. The next year she published her second book,

The Good Earth

, a multimillion-copy bestseller later made into a feature film. The book was the first of the Good Earth trilogy, followed by

Sons

(1933) and

A House Divided

(1935). These landmark works have been credited with arousing Western sympathies for China—and antagonism toward Japan—on the eve of World War II.

Buck published several other novels in the following years, including many that dealt with the Chinese Cultural Revolution and other aspects of the rapidly changing country. As an American who had been raised in China, and who had been affected by both the Boxer Rebellion and the 1927 Nanking Incident, she was welcomed as a sympathetic and knowledgeable voice of a culture that was much misunderstood in the West at the time. Her works did not treat China alone, however; she also set her stories in Korea (

Living Reed

), Burma (

The Promise

), and Japan (

The Big Wave

). Buck’s fiction explored the many differences between East and West, tradition and modernity, and frequently centered on the hardships of impoverished people during times of social upheaval.

In 1934 Buck left China for the United States in order to escape political instability and also to be near her daughter, Carol, who had been institutionalized in New Jersey with a rare and severe type of mental retardation. Buck divorced in 1935, and then married her publisher at the John Day Company, Richard Walsh. Their relationship is thought to have helped foster Buck’s volume of work, which was prodigious by any standard.

Buck also supported various humanitarian causes throughout her life. These included women’s and civil rights, as well as the treatment of the disabled. In 1950, she published a memoir,

The Child Who Never Grew

, about her life with Carol; this candid account helped break the social taboo on discussing learning disabilities. In response to the practices that rendered mixed-raced children unadoptable—in particular, orphans who had already been victimized by war—she founded Welcome House in 1949, the first international, interracial adoption agency in the United States. Pearl S. Buck International, the overseeing nonprofit organization, addresses children’s issues in Asia.

Buck died of lung cancer in Vermont in 1973. Though

The Good Earth

was a massive success in America, the Chinese government objected to Buck’s stark portrayal of the country’s rural poverty and, in 1972, banned Buck from returning to the country. Despite this, she is still greatly considered to have been “a friend of the Chinese people,” in the words of China’s first premier, Zhou Enlai. Her former house in Zhenjiang is now a museum in honor of her legacy.

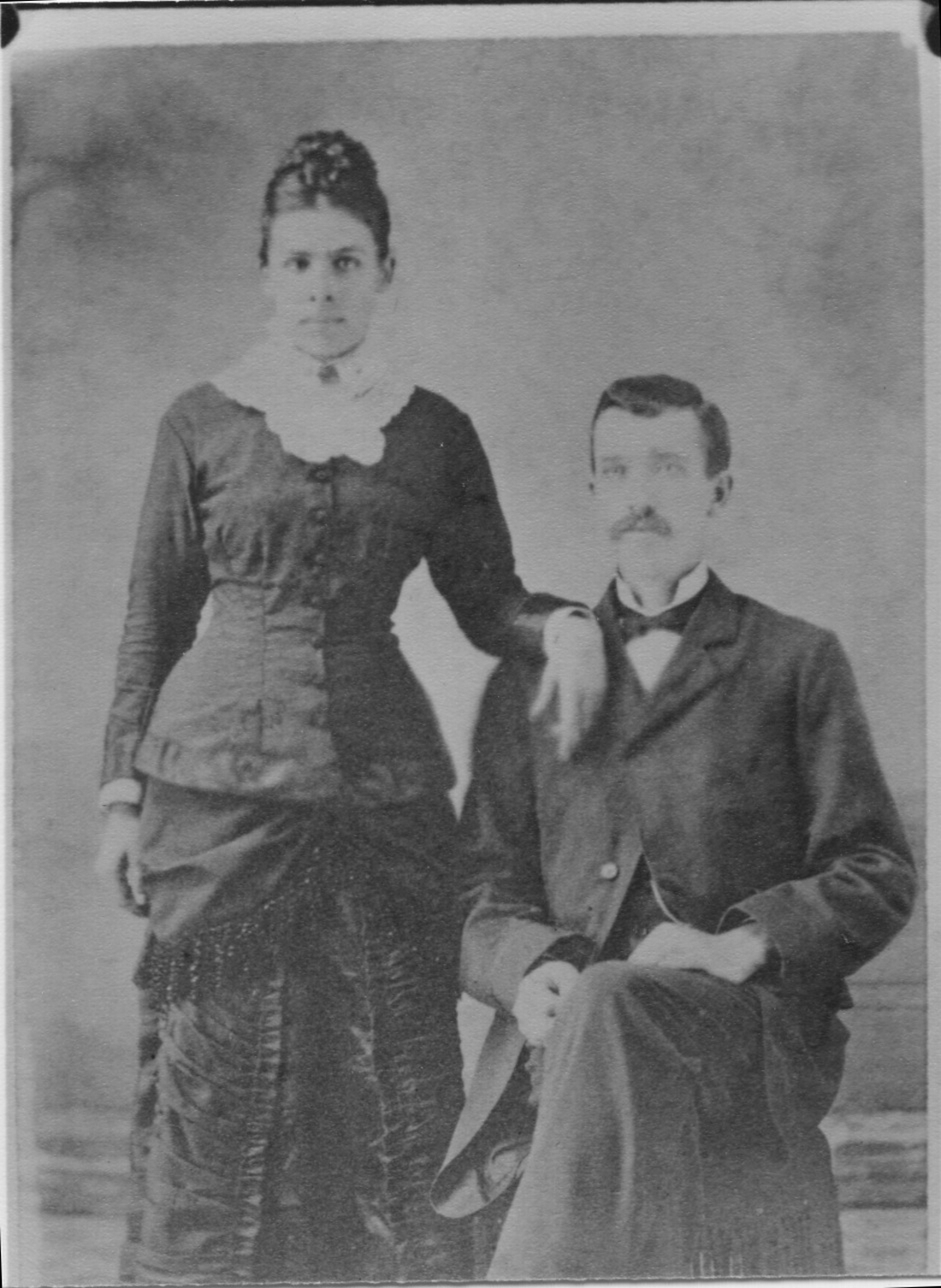

Buck’s parents, Caroline Stulting and Absalom Sydenstricker, were Southern Presbyterian missionaries.

Buck was born Pearl Comfort Sydenstricker in Hillsboro, West Virginia, on June 26, 1892. This was the family’s home when she was born, though her parents returned to China with the infant Pearl three months after her birth.

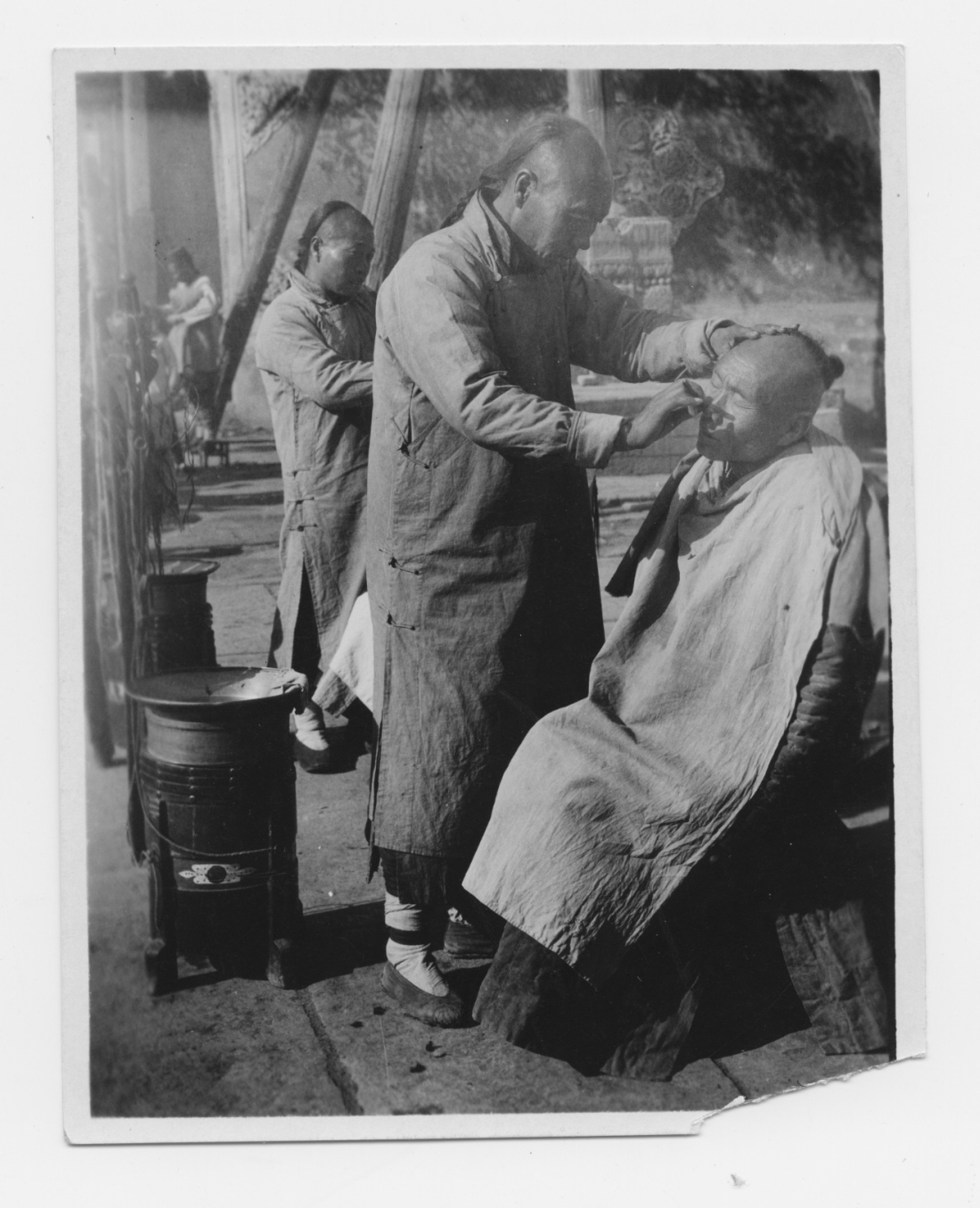

Buck lived in Zhenjiang, China, until 1911. This photograph was found in her archives with the following caption typed on the reverse: “One of the favorite locations for the street barber of China is a temple court or the open space just outside the gate. Here the swinging shop strung on a shoulder pole may be set up, and business briskly carried on. A shave costs five cents, and if you wish to have your queue combed and braided you will be out at least a dime. The implements, needless to say, are primitive. No safety razor has yet become popular in China. Old horseshoes and scrap iron form one of China’s significant importations, and these are melted up and made over into scissors and razors, and similar articles. Neither is sanitation a feature of a shave in China. But then, cleanliness is not a feature of anything in the ex-Celestial Empire.”