A Needle in the Heart (27 page)

Read A Needle in the Heart Online

Authors: Fiona Kidman

‘D’you mean, get over him?’

‘There wasn’t much to get over, was there?’ he says, which as near as he gets to being nasty. She hates him for this niceness, this unfailing kindness about all the silly ruinous things she’s done.

When the barman said, ‘What’re you drinking?’ /I said marriage on the rocks

. Damn song. Over and over.

She does what he says, goes back to study, but she’s slow. It feels as if she’ll never finish her degree. She does some work at the bookshop, and reconnects, as they all say.

Surprise, surprise. One day she comes home and there’s an atmosphere in the house she can’t make out straight away. It’s as if the place has been burgled, but everything is orderly and in place. She opens the wardrobe to put away her coat and all his clothes have gone. The boys have got home from school ahead of her.

‘Have you seen your father?’ she asks.

None of them have. She doesn’t tell them immediately that he’s removed all trace of himself from the bedroom and the bathroom. This happens two years after the night she and Fraser were caught. David is in love with a woman called Marina. She is a thin tanned woman with electric frizzy hair and startling blue eyes, that make her and David look more like siblings than lovers.

‘You bitch,’ James says. ‘It’s your fault.’ He is fourteen at the time. That is the hardest part, the very worst moment. Why James? she has wondered aloud to her friends. It’s the old thing of the first born, they say, offering comfort. You know, the one who is there in the

beginning

, the one who knows everything and never lets you go. But he was always outside, playing in the garden, she will say.

Liese’s pad is scribbled with hieroglyphics from her note-taking at the

play. Coincidences are not a great way to resolve a play, or anything in literature for that matter, but perhaps, she thinks, it’s the way life often resolves itself. Here she is, wondering how to review Hare’s play, and here she is, trapped in the circle of her own past. Her deadline is upon her. The young are afraid of the dark, she writes. They know what’s out there waiting for them, more than we did when we were young. You could say

The Blue Room

is a touchingly moral play, or a very scary one, depending on whether you’ve touched bottom yet, or are still treading water.

When Liese and Ned were still students, eking out and making do, up there at the university, he’d asked her a question she’s never answered. It was one night when there was a party at the end of term (no, not a party — come round for drinks, was what they said now), at one of her lecturer’s houses. She’d just finished her degree and was thinking about going on to a masters. ‘You write so well,’ the lecturer said, a woman she liked, about her own age, with a lean face and owlish spectacles. Later, her lecturer is less impressed with her career as a journo, thinks she could have tried something more literary, but Liese tells her she’s not given to haiku or sonnets. She remembers being a bit tipsy, and not wanting it to show, thinking her transformation complete.

She was standing outside on a balcony, overlooking the harbour, and Ned had come out and stood beside her. ‘Did your marriage break up because of anyone else?’ he’d asked, as if it was something he must know.

She could have brought up the obvious matter of Marina, but this seemed like a lie she didn’t want to tell. Sometimes, to this day, she looks up at family occasions, and sees David looking across at her with a startled puzzled look, as if reaching for something just beyond his grasp, before he sighs and settles back into his new life, the one he took up after he left her, with his new wife and their daughters. She could have told Ned, David left me for Marina; instead, she said nothing, kissed him on the mouth, and found herself being kissed in return. Somewhere, in that still space, she has held on to the truth which so far she hasn’t shared with anyone.

If she hurries, she’ll just make the supermarket, plus a task that she’s set herself at home, before she goes to the concert. She checks her list, making sure it’s current. All these lists drive her crazy, sometimes she finds she’s shopping from last week’s, and she doesn’t need what she finds herself buying. What would anyone make of her list for the weekend, she wonders. How would one be judged by such a list? That she keeps stocked up, stays prepared? That she nests, perhaps, and is content. That she will come home at the end of the day. She and Ned have given each other constancy.

This is her list:

| | toothpaste | olive oil | mushrooms |

| | tom. paste | chicken stock(Tetrapak) | 3 tins whole tomatoes |

| | limes | wine | 2 coconut milk |

| | spinach | basil | eggs |

| | Mex. chili powder | new potatoes | |

| | chicken thigh cutlets (check whether Si and Keith are coming for dinner 6 or 8?) | ||

| | cereal | granny smiths | cheese |

| | 6 pack yoghurt | jar pasta sauce | macaroni |

Not much to be gleaned except, perhaps, a particular culinary domestic trail of a working woman somewhere early in the 21st century. She adds

12 lbs tomatoes, 7 onions

to the list. It’s not the best time of year to lay hands on a case of beefsteaks but she thinks the tomatoes she buys will do. She has the rest of the makings for soup at home. Liese makes Prue’s soup every year, choosing a weekend late in summer. This weekend has chosen itself. The warm homeliness of the finished jars is her annual bow to domesticity.

‘I don’t see why,’ Ned says, shaking his head, as she toils away at churning the pulp through a mouli, ‘you can buy stuff that’s as good these days.’

But it’s not true. This is the best soup, with its rich unparalleled flavour. He knows this; when he eats it he agrees. Just sometimes when she’s making it, she blinks away a thought about how her life

might have been. She thinks she had a lucky escape.

Not that she didn’t see Fraser again.

She went back again, even then, after everything that had happened, and saw him once more. She sees herself, sitting in a battered Prefect, waiting for Fraser to walk down the street to meet her. In the afternoon she has rung him at work and said she would be driving up. She will be there at nine o’clock. She has something she must tell him. His voice, when he registers this, is cool and unfriendly.

‘That’s not a good idea,’ he says. ‘I’d rather you didn’t come.’

‘I’m already on my way,’ she tells him, and hangs up.

It’s cold in the car, a hint of frost, though it’s supposed to be spring. Her limbs feel weighted down. The neighbours wouldn’t recognise the car, but if they see a woman sitting alone as the hours pass, they will come and look, thinking either that she is up to no good, or that she’s in trouble and will have to be helped. Around her, the lights begin to go off. The day before she had sat in the office of a lawyer specialising in divorce. He took snuff, carefully holding one nostril while he listened to her talk, inhaling with noisy snorts while she wept and helped herself to the box of tissues he kept on his desk. A line of peppery mucus dribbled down to his lip. ‘Your husband’s taking you for a ride, woman. What’s the matter with you? I can get you a better settlement than this.’

But she isn’t prepared to argue. In her heart, she believes she’s being served her own rough justice.

It is eleven o’ clock when at last she sees a figure outlined against the street light at the end of the cul de sac. She sees how his head turns, as if listening for something, perhaps the sound of her voice, the way his shoulders hunch as he heads towards her.

‘Why are you here?’ he asks, when he comes alongside her, and the rolled down window of the car. ‘What do you want?’

She wishes she knew. It was just that when she walked out of the lawyer’s office, she wondered if she might have been mistaken.

‘I’m divorced,’ she says.

‘I don’t want to hear this.’

‘I didn’t think you would.’

‘Then why come? What’s the point?’

‘I needed to be sure. Something you said. It’s been quite a high price.’

‘Oh, come on,’ he says, his voice rough, ‘you’re not telling me it was my fault. That was years ago.’

‘You asked me to go away with you,’ she says. They are both whispering but their voices seem loud.

‘You can’t imagine what it’s like to lose a son,’ he says. ‘I thought you’d understand that.’

‘Of course, we talked about that,’ she says, distractedly. ‘No, I don’t really know. But it’s not what you said.’ Their voices, hers anyway, have risen. People will start appearing, looking for strangers in the street. They will see, instead, that it is Liese who is supposed to be hundreds of kilometres away, and that it is Fraser whose had trouble in his home and should be there, comforting his wife. They have known all along, they will say to each other. Although, really, you can tell that Prue is the strong one; she went to pieces for a while but then she snapped out of it, got herself sorted. (Liese has heard this from Brenda who insists on annual visits on the way to the South Island for her holidays. She had been noncommittal when Brenda told her, although she did say, ‘Have you any idea when it was she came right?’ Brenda had looked at her quizzically. ‘It was her faith,’ Brenda said, ‘she’s strong in that, you know.’ Liese didn’t, but she accepts that it might be so.)

‘Unfinished business,’ she says to Fraser. ‘Never mind. I always knew it was Prue you really loved.’ This isn’t true, but as soon as the words are out, she feels as if it is. How could she not have known that Fraser loved beautiful wicked Prue, with her dallying ways, the way she drove him to his crazy acts of defiance. Like being with her.

‘I don’t want to set eyes on you again.’ He turns to walk away, but suddenly she’s angrier than she’s ever been in her life. As he begins to walk down the street, Liese presses the horn. Once. Twice. He stops and comes back.

‘I can’t,’ he says. ‘Don’t you see, I can’t. Besides,’ he says, ‘Prue’s not well.’

For years she lives with the cleanness of her anger. Her life, she thinks, is an old-fashioned morality play: a woman laid low by bad behaviour. Then she meets Ned, and eventually it matters less. Not a well-structured play, but there it is — a bunch of flawed characters, lurching from one thing to another, and it hasn’t turned out so badly.

And now Fraser is dead, and Prue seems remarkably alive, and she is making soup. While she blinks away real and onion tears, she imagines the conversations Prue and Fraser must have had about her, how their own bad times together will have become tragic and romantic and full of nostalgia. He will have told her, it is clear that he must, about the day when they walked on the seafront and talked about dying.

‘I thought you were coming to the concert?’ Ned says, when he comes in.

‘I am,’ she says. The soup is a sexy brilliant red, softly plopping away in the pot. The jars are lined up, hot and gleaming, on the bench, waiting to be filled. ‘This won’t take long.’

‘I don’t get it,’ he says shaking his head.

‘You’re not supposed to,’ she says.

He puts his hand out and touches her arm. ‘Liese. What is it?’

She turns the heat down beneath the soup, turns round and folds her arms, leaning against the bench. The thing is, she tells herself, it’s songs and a poem or two, a box of photographs, recipes and lists, stories and fictions, especially the ones that leave out the worst bits (for there is more to this story, but that’s enough) that get them all through. After all, Prue has listened and remembered. She has asked Liese to come. ‘Once, a long time ago, I had an affair with a married man,’ she says. ‘I was still married to David.’

‘Oh. This is the secret?’

‘Yes,’ she says, ‘this is the secret.’

‘It’s not an unusual story.’

‘But it’s one I haven’t told you.

‘And now you’re going to tell me all about it?’

‘Not really,’ she says. ‘He’s died and his wife wants me to go to the funeral, that’s all.’

‘Ah, now that’s less usual. That’s masochism. So are you going?’

‘No,’ she says, after a moment, because she’s only just decided. ‘I’m not going.’

‘If it’s important to you, you should,’ he says.

‘I think it’s better left. I’ll write her a note.’

‘What will you say?’ he asks.

Liese looks at the soup she’s made; there’s something about its rich dark saucy centre that reminds her of herself, her old self,

carefully

put away for so long, wearing its disguise. A gift from Prue. She’s not glad Fraser is dead; she’s not anything, at last, not even regretful, and that’s the best part of all.

‘I’ll tell her I made it,’ she says. ‘Soup.’ She is thinking about Ned’s music and how she can start listening to it properly, the high notes and the low notes, and savour the still pauses between movements. Like the split second before applause at the end of the play.

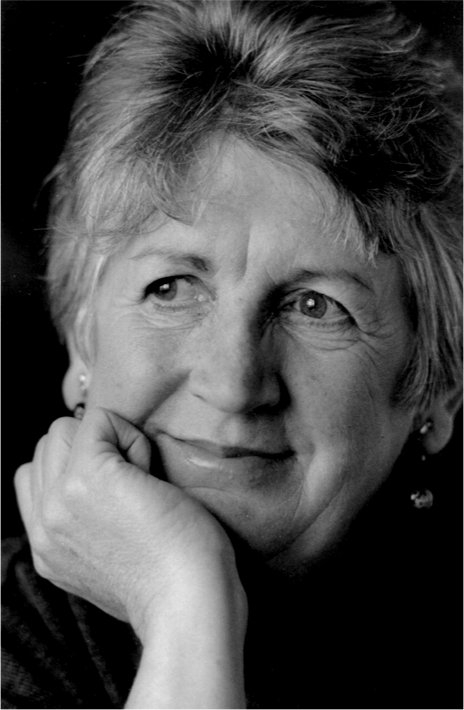

Fiona Kidman was born in 1940. She has worked as a librarian, creative writing teacher, radio producer and critic, but primarily as a writer. To date, she has published 19 other books, including novels, poetry, short story collections, non-fiction and a play. She has been the recipient of numerous awards and

fellowships

, and was created a Dame (DNZM) in 1998 in recognition of her contribution to literature.