A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (35 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

“Monday morning quarterbacks” later pointed out that Dewey gave away a significant tactical advantage by moving his squadron in close to the Spanish fleet. His largest caliber guns had a greater range than any of the opponent's and, by remaining outside his enemy's reach, he could have fired upon the Spanish ships without any risk to his own. But Dewey felt that “in view of my limited ammunition supply, it was my plan not to open fire until we were within effective range, and then to fire as rapidly as possible with

all

of our guns.”

The Asiatic Squadron moved in ever closer to their adversary. Even when the Spanish opened fire, Dewey withheld the order to commence firing. Like so many others, Landsman Tisdale found the tension of waiting, under fire, excruciating. “Our hearts threatened to burst from desire to respond. I sat upon the gun-seat repeating to the rhythm of the engine's throb, âHold your fire . . . hold your fire . . . hold your fire until the bugle sounds,' while my fingers grew numb upon the spark.”

Tisdale, waiting at his station in

Olympia

's after turret, was certainly justified in his anxiety, but there were even more difficult jobs to be accomplished under the circumstances. Because the ships were moving in so close to shore and in danger of running aground, a leadsman was required to stand at the ship's rail, far forward on the open deck, casting his line down into the water to measure the depth. This Sailor had to cast his line, let it hit bottom, retrieve it, and report both the depth and the type of bottomâwhile enemy shells roared through the air and crashed into the nearby water, lifting great geysers of water skyward!

When at last the U.S. ships had closed to within five thousand yards, Commodore Dewey calmly uttered the words to

Olympia

's captain that would be remembered for all time: “You may fire when you are ready, Gridley.”

According to

Olympia

's official log, she commenced firing at 0535. Two-hundred-and-fifty-pound shells erupted from her forward battery and the cruiser shuddered from the eruption. Still in column, only

Olympia

's forward guns were “unmasked” to allow firing at the enemy, and Tisdale still “chafed for the opportunity to fight back.” Dewey's tactics soon remedied the problem. The commodore turned the column to starboard until it was steaming nearly parallel to the Spanish line of ships. Now Tisdale's after turret could be brought to bear on the enemy, as could every American gun that could be trained to port.

The American gunners did not hold back. Long before the phrase “shock and awe” would enter the American lexicon of war, the Asiatic Squadron let loose with all its fury, firing every available gun as quickly as possible to deluge the Spanish fleet with exploding shellfire. On his flagship

Reina Cristina,

Admiral Montojo watched as “the Americans fired most rapidly. There came upon us numberless projectiles.”

Olympia

led the way as the U.S. ships ran along the Spanish line, firing relentlessly as they passed. When they were beyond the enemy line, they executed a tactical “corpen” of 180 degrees, turning in column to preserve the order of ships for another run in the opposite direction. The guns were shifted to starboard for this run, and again a withering fire was brought to bear on the enemy. The Spanish fought back, even as their ships began to burn and splinter apart. They sortied several torpedo boat attacks, but these were driven back by the Americans' smaller guns; even the embarked Marines participated, firing their rifles at the charging boats.

The battle raged on for several passes. These tactical maneuvers ensured that the maximum force of the American guns was brought to bear on the stationary Spanish ships. By keeping his ships immobile, Montojo had traded maneuverability for stability and control. As the battle took shape it became evident that this decision also had made them easily identifiable targets. At last Montojo decided to go on the offensive. Whether he saw it as a tactical venture, designed to gain some military advantage, or as merely an act of defiance for honor's sake is not clear, but he ordered his flagship to get under way and to charge headlong at his tormentors. Apprentice Seaman Longnecher, peering out from his gun port in

Olympia,

could see the Spanish ship coming. “As the

Reina Cristina

came out from the yard to meet us, she planted a shell into the side right at my gun port. But it was spent and did not come all the way through before it burst.” John Tisdale was impressed by the Spanish tenacity. He witnessed one of his after turret's 8-inch shells rip “through and through” the charging Spanish ship, yet “like an enraged panther she came at us as though to lash sides and fight us hand to hand with battle axes, as in the olden Spanish wars.”

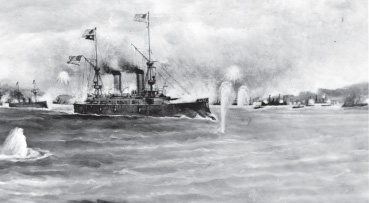

U.S. cruisers attack Spanish ships in Manila Bay in the first big battle of the Spanish-American War.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

But the charge was in vain. On fire and badly mauled,

Reina Cristina

was forced to come about and limp back to her mooring. She was so badly damaged that Montojo soon ordered her abandoned. As she sank, he shifted his flag to another ship.

Reina Cristina

's losses were catastrophic: 150 were killed and another 90 wounded. Five years later, she would be raised from the mud of Manila Bay; the skeletons of 80 men were discovered in her sick bay.

The battle raged on for another half hour, until the smoke became so thick that it was impossible to see what was happening. It was then that Dewey received a most unsettling report. Word came from Captain Gridley that

Olympia

had just fifteen rounds of her heavy-caliber munitions remainingâa mere five minutes' worth of fighting. With the battle undecided as far as he could tell, and in light of this alarming report, Dewey ordered the Asiatic Squadron to withdraw, much to the mixed relief and consternation of the crews. They could not help but be glad for the rest, yet they were “fired up for victory,” as one lieutenant observed.

Moving out of range, Dewey called his captains to

Olympia

for a meeting. He ordered a hot meal for the crews while these officers conferred. Word spread that Dewey had stopped the fight expressly for the purpose of having breakfast. Not a few of the men expressed their dismay and disapproval for that decision. One gunner was heard to say: “For God's sake, Captain, don't let us stop now. To hell with breakfast!”

While the many ate and passed scuttlebutt, the few conferred. Dewey soon learned that the report on low ammunition was in error. He also learned that there had been just six Americans wounded, all in

Baltimore,

and none killed in action.

The smoke eventually cleared substantially, and at 1116 the U.S. squadron headed back in to finish the fight with the enemy. They resumed the bombardment, and in less than an hour all of the Spanish ships were destroyed or put out of action. A white flag appeared over the naval station at Cavite, and the Battle of Manila Bay was over.

From

Olympia

's main deck that night, Wayne Longnecher watched the remnants of the Spanish fleet burning across the water. “It was a beautiful sight to see; besides about 12 or 13 ships all in flames, small magazines were going up all night.” He and his shipmates would never forget that night, nor the day's events that led up to it.

John Tisdale's hitch was up, and soon after the battle, he made his way halfway across the world to return home. He had left California as a young boy, still “wet behind the ears.” He came home a Sailor and combat veteran, with tattoos to tell parts of his story and a newfound confidence that comes to those who have faced great challenges and prevailed.

Upon his arrival in America, Tisdale found the country ecstatic over the U.S. Navy's victory at Manila Bay. Everywhere he went, he heard songs with lyrics praising the great triumph. Banners proclaimed Dewey and his men the “saviors of the Republic,” and newspaper stories spoke of a “new era of American dominance of the sea.”

When the smoke finally cleared, the Spanish fleet had been utterly destroyed, and 381 Spaniards had lost their lives. The Asiatic Squadron had lost not a single man, much less a ship. As in all battles, technology, logistics, and no small amount of courage were major factors in the outcome. But it should be apparent that American tactics were clearly superior to those of the Spanish, and this played no small role in the overwhelmingly favorable outcome of the battle.

Despite this impressive victory, the U.S. strategy for winning the war with Spain was not yet complete. Another Spanish fleet remained in the Atlantic, and until it could be defeated, the war was still undecided.

Commodore Dewey's execution of Mahan's “offensive defense” strategy was not going to work in the Atlantic. Since the outbreak of war, there had been a great deal of anxiety among the American public that the Spanish might send their Atlantic fleet under Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete to attack

cities along the East Coast of the United States. Because the U.S. Navy could not be certain of the location of Spanish forces, it could not risk going on the offensive and leaving the East Coast unguarded. There also was a logistical reason that Rear Admiral William T. Sampson, Commander of the Home Squadron, could not take his ships across the ocean in search of Cervera's fleet: his warships could not carry sufficient coal to make the voyage and then to fight a battle without replenishment. The only strategy available to Sampson was to wait for the Spanish to come to him.

Because Cuba was the root cause of the war, it seemed reasonable that Cervera would most likely take his fleet there. It made good strategic sense, therefore, for Sampson to set up his base of operations at Key West, Florida, just eighty nautical miles from Cuba. But to calm the anxieties of the nation, the Navy created the Flying Squadron under Commodore William S. Schley to remain at Hampton Roads, Virginia, in case Cervera did indeed attempt an attack somewhere along the eastern seaboard.

Cervera left Europe on 28 May 1898 with all the Spanish ships that could be sparedâfour cruisers and two destroyersâand headed for the Caribbean Sea. Sampson's ships had been patrolling the so-called Wind-ward Passage along the northern coast of Cuba in hopes of intercepting the Spanish fleet, but Cervera headed farther south to replenish his coal on the northern coast of South America before heading for Cuba. Successfully eluding the U.S. Navy, Cervera's ships eventually arrived unmolested at Santiago on the southeastern side of Cuba.

With the enemy's position at last fixed, the U.S. Navy could go on the offensive and carry the fight to him. Adhering to another of Mahan's maximsâthat of massing forcesâevery available U.S. ship now converged on the Caribbean. Schley's Flying Squadron was released from its defensive duties to join Sampson's force in the Caribbean, and even USS

Oregon

left her station in the Pacific to make a high-speed run around the treacherous Cape Horn to join the impending battle.

Because Santiago Bay was too small to allow much maneuveringâless than two nautical miles across at its widest pointâand because the narrow entrance was well-defended by gun batteries on either side, going in after the Spanish fleet did not make good tactical sense. Instead, the American ships set up a blockade outside the bay, keeping Cervera's force bottled up for more than a month.

At 0930 on Sunday, 3 July 1898, with the crews of the U.S. ships all preparing for personnel inspection, the battleship

Iowa

suddenly fired a gun to get the attention of all ships. From her yardarm flew the signal flags “two-five-zero.” No one needed to check the codebook. It was what everyone had been anticipating for weeks: “Enemy coming out.”

The Americans were all still clad in their finest white uniforms for the inspection as they dashed to their battle stations. Within minutes, the white duck cloth worn by the stokers in the boiler rooms had been transformed to black as they shoveled coal into the gaping furnaces to build up sufficient steam for the great steel giants to get under way.

The first ship to emerge from Santiago Bay was Cervera's flagship,

Maria Teresa,

leading a column of the other Spanish ships.

Maria Teresa

seemed to be headed straight for the cruiser

Brooklyn,

Schley's flagship. Assuming that the Spanish cruiser was trying to ram, Schley made a tactical decision he would come to regret: he ordered the helm put over to starboard. Cervera did not intend to ram but was attempting to evade instead. By putting his helm over to starboard as well, he caused the two ships to diverge. Schley continued to hold his rudder over so that

Brooklyn

turned through a complete circle, which gave Cervera time to open the distance and make a dash westward along the southern coast of Cuba.