A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (37 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

During the hotly contested struggle for the Solomon Islands during World War II, when Japanese and American Soldiers and Marines were engaged in heavy fighting on Guadalcanal and some of the other islands in the chain, the Imperial Japanese Navy supported their forces ashore by making frequent sorties down a water passage among the many islands that soon became known as “The Slot.” These sortiesâdubbed the “Tokyo Express” by the Americansâled to frequent engagements with U.S. ships in the area and resulted in a number of major naval engagements that proved to be key components in the ongoing campaign.

On the night of 1 August 1943, fifteen U.S. torpedo boats engaged four of these Tokyo Express destroyers. Unlike many other nights, neither side suffered any losses in the fighting. Later, in another part of the passage, one of the U.S. boatsâ

PT 109

âwas unfortunate enough to be lying in the path of

Amagiri,

one of the marauding enemy destroyers. It was a pitch-black night, and neither vessel's captain was aware of the other's presence in the darkened Slot.

A U.S. PT boat, similar to the one on patrol in The Slot on the night of 1 August 1943.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

The fast-moving Japanese ship crashed into the PT boat with great force. The smaller vessel never stood a chance; she was cut in two and her fuel tanks exploded. Two of the American Sailors were killed in the collision and resulting explosion, and several others were badly injured.

The Japanese destroyer continued on down The Slot, and the survivors were left in the dark waters to fend for themselves. Fend they did. With the fitter men helping the more seriously injured, these PT Sailors swam to one of the many islands that make up the Solomons archipelago.

They guessed correctly that no one knew they were there. The crews of the other boats out in The Slot that night had seen the explosion and assumed all hands had been lost. Knowing that theyâparticularly the injuredâcould survive for just a limited time in the inhospitable jungle on the island,

PT 109

's captain devised several plans to try to get them rescued, including swimming out into The Slot in hopes of getting the attention of U.S. vessels on patrol.

The plan that ultimately worked, causing them to be rescued after a week, was a message carved on a coconut shell and delivered to the U.S. forces by friendly natives in the area.

The captain, a young lieutenant from a wealthy family in Boston, was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for heroism, and little more than fifteen years later he was elected president of the United States. On his desk in the Oval Office, he kept a small plaque that quoted a Breton fisherman's prayer: “O God, thy sea is so great, and my boat is so small.”

John F. Kennedy and ten of his crew escaped death that dark night in the Solomons, but he could not escape it in the glaring daylight in Dallas when he was assassinated on 22 November 1963.

To honor the felled president and former Sailor, an aircraft carrier was named USS

John F. Kennedy

and commissioned on 7 September 1968. Seven years later, in an ironic event similar to the collision of the PT boat and the destroyer, the aircraft carrier bearing Kennedy's name was involved in a terrible collision with the cruiser

Belknap.

Reminiscent of the ensuing conflagration in The Slot in 1943, aviation fuel poured down from the carrier's flight-deck refueling stations into the cruiser's superstructure, causing a horrific fire that burned most of the night and melted

Belknap

's superstructure. Heroic efforts saved the ship, but six

Belknap

Sailors and one from

Kennedy

died, and many others were seriously injured.

The coincidence of collision was bizarre in its own right, but even more amazing was that out of 365 possible days in a year that the collision between USS

Belknap

and USS

John F. Kennedy

could have occurred, this disaster took place on the night of 22 November 1975â

the twelfth anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Strange, but true.

USS

Belknap

after her collision with USS

John F. Kennedy. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

There is an area of the Atlantic Ocean off the southeastern United States popularly known as the “Bermuda Triangle,” or sometimes the “Devil's Triangle.” These waters have a long-standing reputation for mysterious happenings, not the least of which are unexplained disasters. No nautical charts show this area under either popular name, and the U.S. Board of Geographic Names does not officially recognize it, but the apexes of this triangle are generally accepted to be Bermuda, Florida, and Puerto Rico. The U.S. Coast Guard is “not impressed with supernatural explanations of disasters at sea,” explaining that “the combined forces of nature and unpredictability of mankind outdo even the most far-fetched science fiction many times each year.” Yet “strange but true” is an apt description for this part of the world, where many vessels and aircraft have been lost without explanation and often without a trace.

While no one has ever been able to prove any direct correlation, some characteristics of the Bermuda Triangle may be worth noting. The unpredictable Caribbean-Atlantic weather pattern in this area might well play a role; sudden local thunderstorms and waterspouts frequently occur in this area. The topography of the ocean floor varies from extensive shoals around the islands to some of the deepest marine trenches in the world. With the interaction of strong currents over the triangle's many reefs, the topography is in a state of constant flux, and new navigational hazards can develop rather quickly.

One of the most interesting facts about this triangle is that it is one of only two places on Earth where there is no compass variationâboth gyro and magnetic compasses are perfectly aligned in this area. The other region where this occurs is just off the east coast of Japan. Japanese and Filipino seamen call it the “Devil's Sea” because it too is known for the mysterious disappearances in its waters. As most mariners know, compass variation in the rest of the world is a factor that must be reckoned with constantly and can sometimes amount to as much as 20 degrees' difference between true and

magnetic north. What, if anything, this lack of variationâa seemingly good thingâmight have to do with the strange occurrences in the area is anyone's guess, but it is a fact that adds to the region's mysteriousness.

Whether there are scientific explanations for these strange events or they are merely the kind of coincidence that myths are made of, the Bermuda Triangle was the scene of two incidents involving the U.S. Navy that have served to enhance the legendary stature of this area.

One of those incidents occurred during World War I and involved a Navy ship with the mythological name

Cyclops.

The U.S. Navy played a number of important roles in that conflict, known at the time as the “Great War.” Escorted by destroyers, the Cruiser Transportation Force and the Naval Overseas Transportation Service carried more than two million Soldiers and 6.5 million tons of cargo to Europe, dramatically reducing the number of Allied ships lost to German submarines in the process. Naval aircraft, flying from European bases, aided U.S. destroyers in the antisubmarine effort, including the bombing of German bases at Zeebrugge and Ostend. Large U.S. Navy minelayers sowed some sixty thousand mines in the great North Sea mine barrier, which was designed to deny German submarines access to open waters. A division of U.S. battleships joined the British Grand Fleet in the North Sea to contain the German High Seas Fleet; in the Mediterranean, U.S. subchasers distinguished themselves by protecting Allied ships from submarine attack. And, in an unusual development, U.S. naval elements fought ashore in France using huge 14-inch guns that were mounted on railroad cars and served by seaman gunners. In the final analysis, control of the sea approaches to Europe made victory for the Allies possible. Sailors in the U.S. Navy, together with their allies in the Royal Navy, were the instruments of that control.

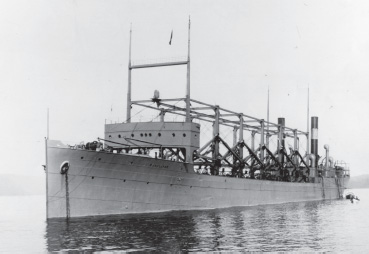

Because this was the age when many ships were coal-fired, Navy colliers (coal carriersâforerunners to today's oilers) played an essential role by ensuring that adequate supplies of coal were available where needed. USS

Cyclops

was one such collier and, soon after the United States entered the war in 1917, she was tasked with fueling British ships operating in South American waters.

Returning to U.S. waters early in 1918,

Cyclops

was in Norfolk, Virginia, when she received orders to carry coal to Brazil and then return to Baltimore with a load of manganese ore. Having safely delivered her coal to Rio de Janiero, she departed Brazil for the return trip on 16 February. After a short stop at Barbados on 3 and 4 March, she was under way again, headed through the Bermuda Triangle en route to a scheduled arrival in Baltimore on 13 March. On board were 306 people, including her crew, an

American consul general, and 72 other passengers, mostly Sailors on leave, changing duty stations, or headed home to muster out of the Navy.

Cyclops

never arrived. In those days of limited communications and rather primitive tracking systems, it took a while before anyone realized the ship was overdue. On 23 March, the Navy launched a search operation to find the missing ship. All the ships that could be spared fanned out over the Bermuda Triangle looking for the missing collier. The search continued until 1 June, when Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt at last declared

Cyclops

officially lost and all embarked personnel legally deceased.

Not a single trace of the 542-foot long, more than twenty-thousand-ton ship and her 306 passengers and crew was ever found. The Navy followed up with an investigation that spanned a decade and is recorded in some fifteen hundred pages of interviews and testimony in the National Archives. Because the nation was at war at the time, an obvious possible explanation for the ship's disappearance was that a German submarine sank her, but after the war, German records were searched and nothing was found that indicated any such attack took place. Many other theories were officially investigated and many more have been offered, but to this day, the mystery of the disappearance of USS

Cyclops

has never been solved.

The Navy again found itself faced with a mysterious disappearance in the infamous Bermuda Triangle shortly after the end of World War II. At about 1400 on the afternoon of 5 December 1945, Flight 19âconsisting of five Avenger torpedo bombersâdeparted from the U.S. Naval Air Station, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, on an advanced overwater navigational training flight. The pilots and their crews were to execute “Navigation Problem No. 1,” which was described thus: “(1) depart 26 degrees 03 minutes north and 80 degrees 07 minutes west and fly 091°T, distance 56 miles, to Hen and Chickens Shoals to conduct low level bombing; after bombing, continue on course 091°T for 67 miles; (2) fly course 346°T, distance 73 miles, and (3) fly course 241°T, distance 120 miles; then return to U.S. Naval Air Station, Fort Lauderdale, Florida.”