A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (38 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

The collier (coal ship) USS

Cyclops. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

In charge of the flight and piloting one of the aircraft was a senior qualified flight instructor. The other planes were piloted by qualified pilots with between 350 and 400 hours' flight time, at least 55 of which were in this type of aircraft. The weather conditions over the area covered by the track of the navigational problem were considered average for training flights of this nature, though there were a few thunderstorms in the area.

At about 1600, a shore-based radio station intercepted a radio message between the flight leader and another pilot. The message indicated that the aircraft were apparently experiencing some kind of compass malfunction and that the instructor was uncertain of his position and could not determine the direction of the Florida coast. Attempts to establish further communications on the training frequency were unsatisfactory because of interference from Cuban radio stations and a great deal of static caused by atmospheric conditions. All radio contact was lost before the exact nature of the trouble or the location of the flight could be determined.

All available facilities in the immediate area were called upon to locate the missing aircraft and help them return to base. These efforts were not successful. No trace of the missing airplanes or their crews was found even though an extensive search operation was launched and continued for five days. On the evening of 10 December weather conditions deteriorated to the point that further efforts became unduly hazardous.

To further compound the mysteriousness of the situation and add to the legend of the “Devil's Triangle,” a Navy patrol plane, which was launched at approximately 1930 on 5 December to search for the missing torpedo bombers, also was neither seen nor heard from after takeoff. No trace of that plane or its crew was ever found.

In a twist of fate, in 1991 a salvage ship found five Avengers in six hundred feet of water off the coast of Florida. It appeared that Flight 19 had at last been located. But examination of the planes showed that they were not the same aircraft that had taken off as Flight 19, so the final resting place of the planes and their crews is still one of the many secrets of the Bermuda Triangle.

In 1977, the now-classic movie

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

offered

an explanation for the disappearance of Flight 19 that is not likely to find its way into official Navy records. It is likely, however, that reasoned theories and fanciful explanations of the strange happenings in the Bermuda Triangle will continue as long as there are unanswered questions and odd coincidences. Such strange but true occurrences have always added to the mystery of the sea.

When the frigate USS

United States

was commissioned in 1797, she was the first American warship to be launched under the naval provisions of the Constitution of the new nation that had won its independence from Great Britain just a few years before. Built in time to participate in the Quasi-War with France, she captured a number of French privateers and recaptured several American ships that had been taken by the French.

In 1812, a new threat arose when Britain challenged the sovereignty of the new nation, and the United States again went to war for its independence and its honor. At the time, Britain's Royal Navy was unquestionably the most powerful one in the world; the fledgling U.S. Navy did not seem to have any chance against so formidable a force. Even though a fleet engagement between the two navies was out of the question, that did not stop courageous American Sailors from engaging the British in ship-to-ship actionsâand winning! A series of victoriesâUSS

Essex

captured HMS

Alert,

frigate

Constitution

defeated the British frigate

Guerrière,

and USS

Wasp

took HMS

Frolic

âstunned the British public and drove up insurance rates at Lloyd's of London. The next victory belonged to USS

United States

; she not only defeated the frigate HMS

Macedonian

but also actually brought her back to New York City to ultimately serve in the American Navy. The capture of a British warship created a huge sensation, raising American spirits at a time when the war was not going well on other fronts.

Such a celebrated beginning seemed to promise a glorious career for the ship bearing the name of her country. But her luck changed. Never again would she fight a major battle. No more would she be the subject of newspaper headlines and the talk of the social circuit. She was destined for an ignominious end.

After the damage from her glorious battle had been repaired,

United States

left New York to rejoin the war, accompanied by USS

Hornet

and her former adversaryâHMS

Macedonian

âwho had also been repaired and was now christened USS

Macedonian.

Within a week, however, the three ships were chased into New London, Connecticut, by a powerful British squadron, and there they were forced to remain until the end of the war.

The frigate USS

United States

battling the British frigate HMS

Macedonian. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

A chance to get back into action seemed imminent when America declared war on Algiers in February 1815 and

United States

was assigned to a squadron preparing to head for the Mediterranean to fight the so-called Barbary pirates of North Africa. But

United States

was in a state of bad repair from her long stay in New London under blockade, and she was unable to leave with the rest of the squadron. When she at last got to the Mediterranean, she remained there until 1819 but never participated in anything other than patrols. While her presence in North African waters was important, it was a bit of an inglorious comedown for the famous frigate that had once prevailed against the Royal Navy.

In the years that followed,

United States

would go into and out of service, periodically deploying to various parts of the world, participating in antislavery patrols, but never doing anything like the action of her early days. Herman Melvilleâlater the renowned author of

Moby Dick

and other classic novelsâsailed in her for a time. Whether it was more a reflection of him or the ship he served in is a matter of conjecture, but he had little of a positive nature to report when he chronicled his experiences in

White-Jacket.

From 1849 until 1861,

United States

rotted away in Norfolk, Virginia, and might well have ended her days that way except for the outbreak of the American Civil War. On 20 April 1861, the Navy Yard at Norfolk was captured by Confederate troops. Before leaving the yard, Union Sailors burned the ships that could not be gotten under way. But they failed to torch

United States,

believing it unnecessary to destroy the decayed relic. The Confederates, pressed for vessels in any kind of condition, repaired the ship and commissioned her CSS

United States.

“Confederate States Ship

United States

” seemed a bit odd to many, so she was often referred to as CSS

Confederate States.

Beyond her seaworthy days, she nonetheless was fitted out with a deck battery of nineteen guns for harbor defense and served as a receiving ship for newly reporting Sailors of the rebel navy.

In this role, she served her new owners well, but when the Confederates were forced to abandon the Navy Yard in May 1862, they decided to sink her in the middle of the Elizabeth River to form an obstruction to oncoming Union vessels. Surprisingly, the old girl did not give up without a fight. The ancient timbers of the frigate were found to be so strong and well preserved that the men trying to scuttle her ruined a whole box of axes in the attempt. Ultimately, they had to bore through her hull from inside before she would settle to the muddy bottom of the river.

Once Norfolk was again under Federal control, she was raised and towed to the Navy Yard. There she remained until December 1865, when the Bureau of Construction and Repair's earlier orderâthat she be broken up and her wood soldâwas at last carried out.

It was a sad ending for a ship whose beginnings had been so promising. It was also somehow unsettling for a ship with so important a name to have gone the way she had. But no one seemed to have given much thought to the matter at the time and for a long time after.

Then, on 25 September 1920, the keel was laid for a new

Lexington

-class battle cruiser in the Philadelphia Navy Yard, and the new ship was given the name

United States.

It seemed for a while that the old meaningful name was to be resurrected, and hopefully the glorious heritage of her predecessor would pass on to this new powerful ship now under construction.

But it was not to be. World politics intervened, and on 8 February 1922, with the ship barely 12 percent complete, construction was halted in compliance with the Treaty for the Limitation of Naval Armaments. This treaty had been signed by the United States and other world naval powers in an attempt at arms limitation with the hope of preventing future war. The unfinished hulk of the would-be

United States

was sold for scrap in October of the following year. (Ironically, the treaty also ultimately ended up as a

meaningless scrap of paper when some years later the world's greatest sea war was fought on all the seven seas.)

In the spring of 1949 the keel was laid for another

United States.

This one was to be a “super carrier,” designed to meet the challenges of the developing superpower confrontation with the Soviet Union by her ability to launch long-range aircraft equipped with atomic weapons.

This time internal politics intervened. Just five days after her keel-laying, work was terminated at the order of the secretary of defense, who had decided that aircraft carriers were no longer needed because U.S. Air Force bombers alone were capable of fighting the Soviet Union should war come. This tipped off a major battle between the two services, provoking Secretary of the Navy John L. Sullivan to resign in protest and causing what has come to be known as the “revolt of the admirals,” when senior officers in the Navy put their careers on the line to express their serious concerns before Congress. It was not a happy time for the nation or its defense establishment. Chief of Naval Operations Louis Denfield was relieved of his command as a result of the “revolt,” and the war of words between the Navy and Air Force continued for some time. The debate was finally ended when North Korea invaded South Korea, and U.S. aircraft carriers played a vital role in holding off the enemy onslaught until more forces could arrive to launch a successful counterstrike at Inchon.

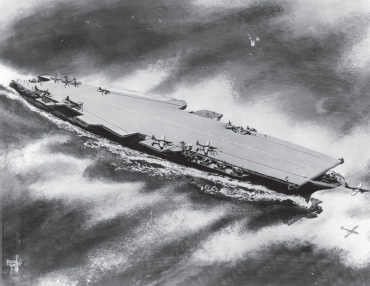

An artist's sketch of what was supposed to be the “super carrier” USS

United States. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

All of this started when the name

United States

was once again assigned to a Navy ship! Talk of a jinx began to circulate.

These superstitious rumblings had not yet quieted when again, in November 1993, another

United States

was laid down. This one was to be an even bigger, more capable shipâa

Nimitz

-class nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. But fourteen months after construction was begun, the decision was made to rename the ship USS

Harry S. Truman,

to honor the thirty-third president of the United States. While few debated the wisdom of naming a ship after the commander in chief who had first gone to war against Communismâand there was nothing sinister or deliberate in thwarting plans for another

United States

âfor those who subscribe to such things, it was not a great leap to imagine that a jinx was at work.

To this day, there has never been another ship in the U.S. Navy named USS

United States.

Blaming a jinx may not be logical, but it certainly seems to fit this situation.