A Singular Woman (19 page)

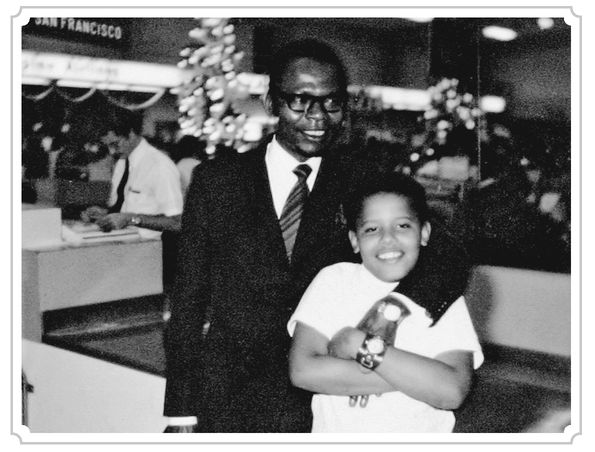

With Barack Obama Sr., Christmas 1971

Ann returned to Indonesia in early 1972, after the Christmas visit, and negotiated a leave of absence from her job in Jakarta in order to enter graduate school at the University of Hawaiâi. She even managed to line up some financial support through a foundation grant to the management school where she had been working. Taking Maya with herâand for a time, Loloâshe returned to Hawaii and found her way that fall into the master's-degree program in anthropology, the field that had been her undergraduate major. In an application to the East-West Center in December 1972, she described her academic specialization as economic anthropology and culture change. “But I'm more interested in the human and psychological factors that accompany change than purely technological factors,” she wrote. She said she was planning “a possible joint project” with Lolo, who was involved in a population-studies program under the department of geography. But Lolo did not stay long. He remained enrolled only for the spring semester of 1973, according to university records. By the time of the cross-country bus trip in July, he was gone.

Barack Obama Sr. and the young Barack, Christmas 1971

By that summer, Ann had landed a grant from the East-West Center to cover her university tuition and field research. Married students with children were exempt from the East-West Center requirement that students live together as a community in the center's dorms, but the housing allowance was too low to permit students to live above the poverty level in Hawaii, said Benji Bennington, who had become an administrator at the center. So Ann found an apartment in a low-slung, cinder-block building reminiscent of a budget motel, with hot water heaters on the balconies and utility meters bolted to the outside wall. The apartment, on Poki Street, was a mile and a half from the university and a short walk from both the Dunhams' apartment and Barry's school. She furnished it with the help of a furniture pool run by the off-campus housing specialist for the East-West Center, who also helped many of the students qualify for food stamps. When Ann overheard Barry's school friends commenting on the limited refrigerator inventory and his mother's unimpressive housekeeping, he says, she would take him aside and let him know that as a single mother back in school, baking cookies was not at the top of her priority list. She was not, she made it clear, putting up with “any snotty attitudes” from him or anyone else.

The status of Ann's marriage was ambiguous, it seems. According to Obama's account, Ann had separated from Lolo. But that was less clear to her friends. “She certainly considered herself married,” said Kadi Warner, who was also a graduate student in anthropology on an East-West Center grant when she met Ann in the early 1970s. “But she had a different sense, perhaps than he did, of what that meant.” Lolo, calling from Jakarta to speak with Maya, would be in tears. “Ann thought it was cute and amusing but nothing like, âI have to pick her up and go back,'” Warner said. “Her thing was, âYou just have to do this to finish school, that's how it is. This is what we have to do.'” Her attitude seemed to be that she and Lolo were married, they would see each other occasionally, and that was what adults did when they had other obligations. She intended to work, to make a living, and to at least contribute to, if not fully underwrite, the education of her children. She had returned to Hawaii because she knew she would need an advanced degree, her friend Kay Ikranagara told me. That required that she live apart from Lolo, at least for a time. “Clearly, Ann put her children's education above all,” Ikranagara said.

Ann was unlike the other graduate students in her department. She was older than most and, in effect, a single mother. It was unusual for women to go back to school, especially with young children, or to start a family while preparing to do fieldwork. “When I showed up wearing maternity clothes, my professor came up to me and said, âYou're kidding, right?'” said Warner, who became pregnant several years later. (She promised her professor, she told me, that she would not give birth in class.) Ann was not simply a mother, she was raising two biracial children with different fathers. “It struck me that she was doing something unusual and dangerous and difficult, raising multicultural children on her own,” said Jean Kennedy, another graduate student. Kennedy, who had grown up in what she described as a racially stratified university town in New Zealand, had become intrigued with Southeast Asia after a group of Indonesian, Malaysian, and Thai students arrived on the campus where she was an undergraduate. She had gotten interested in how people would “sort themselves,” as she put it, in the future. “Somebody like Ann, who was cutting across all of this with such strong-minded determination to cut the bullshit and get on with what needed to be doneâI admired her,” Kennedy said. “I could barely make it as a graduate student, and could not even think about getting myself into these sorts of conflicts and responsibilities.”

There was something almost matronly about her. By the time she reached her early thirties, Ann had been an adult for a long time. Other students went out drinking, lay on the beach, flirted, gossiped, threw parties, shied away from commitments, toyed with trendy academic ideas. They lived in what Kennedy called “capsules of theoretical, highfalutin nonsense, very far from the real world.” Ann kept her distance from the chitchat, both theoretical and social. She seemed to be looking for a way to pursue her interestsâin anthropology, in Indonesiaâwhile also making a living. Ben Finney, a professor who had grown up in Southern California and had written an ethno-history of surfing, was put off initially by what he took to be Ann's well-bred manner. Her fastidious diction reminded him of WASPs he had encountered as a graduate student at Harvard. “We did things much more informally than she seemed to,” he said. “After I got to know her, I said, âWell, Ann is just this upright person. That's her, no problem.'” She had an inquiring mind, and she was endlessly curious. She was absorbed by handicrafts, a topic that was not trendy but that interested Finney, too. He had done fieldwork in Tahiti, where, he said, traditional craft industries had all but disappeared, supplanted by the production of whatever tourists would buy. He had seen the strength of the handicraft sector of the Indonesian economy, where craftspeople still made textiles, tools, ceramics, and other items for everyday life. It was one of the reasons, he said, why anthropologists loved Indonesia: the persistence of a recognizably Indonesian way of life. But some had ruled out working there because of the difficulties inherent in getting the government's permission. Ann, however, had already lived there and was going back. Between the fall of 1972 and the fall of 1974, she completed sixty-three credits and all the coursework required for her Ph.D. When I asked Alice Dewey, the chairman of Ann's dissertation committee, what Ann was like as a student, she answered, “Ah! All business.”

Ann's application had caught the attention of Dewey, a professor of anthropology who had gone to Java herself in the early 1950s as a twenty-three-year-old graduate student on a field team from Harvard. Settling in a town in east Central Java that they called Modjokuto, the members of the team did pioneering work on subjects ranging from the Javanese family to the rural economy. Their work became the basis of a series of seminal books, the best known of which was

The Religion of Java

by Clifford Geertz, who went on to become the most celebrated anthropologist of his generation. Dewey studied peasant markets, which are run by women in Java. She lived for more than a year in a rural village north of Modjokuto, bicycling every morning into the main Modjokuto market, spending afternoons visiting the homes of the market people, and passing the evenings on visits to her neighbors. Her most important market informants were two middle-aged half sisters, one of whom sold coffee and hot snacks “and provided me not only with information about her own business affairs but also with the current gossip of the marketplace, of which she had extensive knowledge because coffee stands are important social centers,” Dewey wrote later. “Her half sister, who dealt first in dried corn and later in onions, was the most important informant for my study of wholesaling. She, her husband, a married daughter, and a son, married while I was there, were all experienced traders; between them, with great patience, they managed to teach me the workings of the market.” Dewey's 1962 book

Peasant Marketing in Java

covered, among other things, bargaining, the division of labor, trade discounts, loans and interest rates, moneylenders, pooled savings plans, traders' rights and privileges, interpersonal relationships in the marketplace, small-scale cash crops, mountain crops, prepared-food vendors, and door-to-door peddlers. It also touched on the role of craftsmen, including metalworkers, leatherworkers, tailors, and bicycle repairmen. The book was, Jean Kennedy told me, not fashionable but brilliantâ“a piece of pioneering work that seemed to have been bypassed.” Koentjaraningrat, an Indonesian anthropologist and the author of

Javanese Culture,

a sweeping survey of scholarly work on the subject, called Dewey's book “the best and most comprehensive study on the Javanese market system.”

The Religion of Java

by Clifford Geertz, who went on to become the most celebrated anthropologist of his generation. Dewey studied peasant markets, which are run by women in Java. She lived for more than a year in a rural village north of Modjokuto, bicycling every morning into the main Modjokuto market, spending afternoons visiting the homes of the market people, and passing the evenings on visits to her neighbors. Her most important market informants were two middle-aged half sisters, one of whom sold coffee and hot snacks “and provided me not only with information about her own business affairs but also with the current gossip of the marketplace, of which she had extensive knowledge because coffee stands are important social centers,” Dewey wrote later. “Her half sister, who dealt first in dried corn and later in onions, was the most important informant for my study of wholesaling. She, her husband, a married daughter, and a son, married while I was there, were all experienced traders; between them, with great patience, they managed to teach me the workings of the market.” Dewey's 1962 book

Peasant Marketing in Java

covered, among other things, bargaining, the division of labor, trade discounts, loans and interest rates, moneylenders, pooled savings plans, traders' rights and privileges, interpersonal relationships in the marketplace, small-scale cash crops, mountain crops, prepared-food vendors, and door-to-door peddlers. It also touched on the role of craftsmen, including metalworkers, leatherworkers, tailors, and bicycle repairmen. The book was, Jean Kennedy told me, not fashionable but brilliantâ“a piece of pioneering work that seemed to have been bypassed.” Koentjaraningrat, an Indonesian anthropologist and the author of

Javanese Culture,

a sweeping survey of scholarly work on the subject, called Dewey's book “the best and most comprehensive study on the Javanese market system.”

Dewey, hired by the University of Hawaiâi in 1962, had arrived on campus shortly after the elder Obama graduated and headed for Harvard. Over the years, she would become a mentor and friend to generations of graduate students, serving on countless doctoral committees and dispatching dozens of young anthropologists into the field, armed with what she considered to be four essentials: a flashlight, a penknife, heavy string, and a few mystery stories. (Dewey, who received

The Complete Sherlock Holmes

for her thirteenth birthday, once explained to me in some detail the uses of the first three. Then she added, “The reason for the mystery stories is self-evident.”) The year Ann applied to the anthropology department to do graduate work, Dewey was on the committee that reviewed applications. “She obviously knew her way around Indonesia,” Dewey told me. Ann spoke Indonesian fluently, she was knowledgeable about all things Indonesian, and her interest in handicrafts intersected with Dewey's interest in markets.

The Complete Sherlock Holmes

for her thirteenth birthday, once explained to me in some detail the uses of the first three. Then she added, “The reason for the mystery stories is self-evident.”) The year Ann applied to the anthropology department to do graduate work, Dewey was on the committee that reviewed applications. “She obviously knew her way around Indonesia,” Dewey told me. Ann spoke Indonesian fluently, she was knowledgeable about all things Indonesian, and her interest in handicrafts intersected with Dewey's interest in markets.

“I said, âI want this one,'” Dewey recalled.

Dewey was charmingly unconventional herself. A granddaughter of John Dewey, the American philosopher and educator, and a descendant of Horace Greeley, the crusading newspaper editor, Alice Greeley Dewey had grown up in Huntington, Long Island, with a certain amount of parental license to be fearless. In games of cowboys and Indians, her sympathies did not incline toward the cowboys. As a high school student, she worked in what is now the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, where James D. Watson would deliver his first public lecture on his discovery, with Francis Crick, of the double-helix structure of DNA. At Radcliffe College, she was lured into cultural anthropology by the enticing prospect of field research. Fieldwork, she once told me, comes as close as any experience to being somebody else: “Because they don't know who you are.” She wanted to go to China, where her grandfather had lived, but Mao Zedong had proclaimed the People's Republic of China two years earlier, and the United States and China were fighting on opposite sides in the Korean War. So when her professor suggested Java, Dewey jumped at the chance. Arriving in Indonesia in 1952, she and the other members of the field team were introduced to a cousin of the sultan of Yogyakarta, and his wife, who was affiliated with the junior court. The couple took the students under their wing, getting them in to performances of shadow-puppet theater, gamelan music, and Javanese dance at the palace. Men in batik and turbans wandered barefoot through the lantern-lit halls, speaking high Javanese. “If I had walked into the court of King Arthur, I couldn't have been in more of a fairyland,” Dewey remembered. She became captivated by Java, returning again and again over many decades. In 1989, at the investiture of Sultan Hamengku Buwono X in Yogyakarta, Dewey was in attendance.

Generous and tolerant, Dewey had a reputation for accepting the world on its own terms. “She felt that things work the way they do because they make sense that way, and that people are ultimately rational,” said John Raintree, a former student of Dewey's. “If you don't understand why somebody is saying or doing something the way they are, then you don't understand their point of view. This is the article of faith for those of us who've worked in developmentâtrying to explain that. Alice communicated that to her students.”

In 1970, two years before Ann resurfaced on the University of Hawaiâi campus, Dewey acquired a handsome old house in MÄnoa, a short bicycle commute away from the campus. One of the attractions, as she told me, was a tree in the garden that produced avocados the size of footballs. The house also had four bedrooms, solving Dewey's dilemma, being a globetrotting anthropologist with a fondness for big dogs. Dewey recruited graduate students as housemates, along with, at various times, two German shepherd mixes, a Newfoundland, a gray cat, a Great Dane that matched the cat, and a kitten that matched the Newfoundland. There were also zebra finches, Java ricebirds, a waxbill, and other birds. By the time I saw the place in 2008, the house had settled into a state of advanced dilapidation. A botanical census of the garden would have included jacaranda, breadfruit, miniature mangosteen, lychee, Surinam cherry, rose apple, macadamia nut, cashew nut, yellow shower, tangerine, lemon, banana. Avocado pits, lobbed out a side door, had given birth to an avocado grove. An abandoned car had been reborn as a planter. “Trespassers will be eaten,” read one of several plaques by the door. Jean Kennedy recalled arriving at the house for the first time in 1970 and finding every door wide open. Making her way to the kitchen, she called out and waited for a response.

Other books

Riding on Air by Maggie Gilbert

Anything Can Be Dangerous by Matt Hults

A Girl's Best Friend: An Erotic Shapeshifter Paranormal Romance by Connor, Cara B.

Sister's Revenge: Action Adventure Assassin Pulp Thriller Book #1 (Michelle Angelique Avenging Angel Assassin) by Lori Jean Grace, S. Jay Jackson

Open Country by Warner, Kaki

The Cost of Hope by Bennett, Amanda

Masterpiece by Juliette Jones

Naomi & Bradley, Reality Shows... (Vodka & Vice, the Series Book 3) by Angela Conrad, Kathleen Hesser Skrzypczak

The Lost Star Episode One by Odette C. Bell

Blind Run by Patricia Lewin