A Singular Woman (15 page)

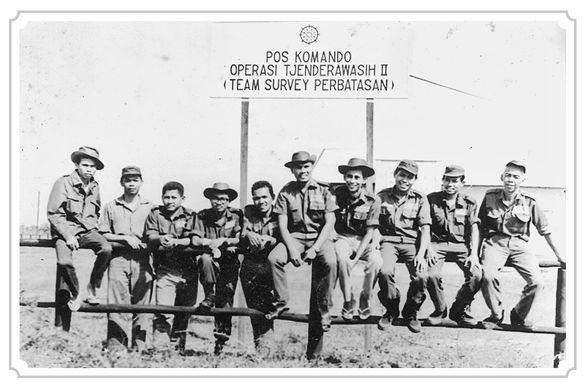

The households in which Ann and Lolo lived in Jakarta in the late 1960s and early 1970s were neither grand nor impoverished by Indonesian standards. When Ann arrived in 1967, Lolo was in the army, fulfilling the commitment he had made to the government in return for being sent abroad to study. He had been sent to Irian Barat, the contested area that would later become Papua, Indonesia's twenty-sixth province. He served as a member of a team assigned to map the border. (A photograph taken in Merauke, a former Dutch military post and one of the easternmost towns in Indonesia, dated July 30, 1967, shows Lolo and nine other men in uniform arrayed along a fence line beneath a sign that reads “Operasi Tjenderawasih II (Team Survey Perbatasan),” or “Operation Cenderawasih, Border Survey Team.”) As long as he was in the military, Lolo's salary was low. On her first night in Indonesia, Ann complained later to a colleague, Lolo served her white rice and

dendeng celeng

âdried, jerked wild boar, which Indonesians hunted in the forests when food was scarce. (“I said, âThat's delicious! I love it, Ann,'” the colleague, Felina Pramono, remembered. “She said, âIt was moldy, Felina.'”) Lolo's pay was so paltry, Ann later joked, it would not have covered the cost of cigarettes (which she did not smoke). But Lolo had a brother-in-law, Trisulo, who was a vice president for exploration and production at the Indonesian oil company Pertamina. When Lolo completed his military service, Trisulo, who was married to Lolo's sister, Soewardinah, used his contacts with foreign oil companies doing business in Indonesia, he told me, to help Lolo get a job in the Jakarta office of the Union Oil Company of California. By the early 1970s, Lolo and Ann had moved into a rented house in Matraman, a middle-class area of Central Jakarta near Menteng. The house was a

pavilyun,

an annex on the grounds of a bigger main house, according to a former houseboy named Saman who worked in those years for Lolo and Ann. It extended straight back from the street, perpendicular to the roadway, into a garden. It had three bedrooms, a kitchen, a bathroom, a library, and a terrace. Like the households of other Indonesians who could afford it, and of foreigners living in Indonesia, it had a sizable domestic staff. Two female servants shared a bedroom; two menâa cook and the houseboyâslept mostly on the floor of the house or outside in the garden, according to Saman. The staff freed Ann from domestic obligations to a degree that would have been almost impossible in the United States. There were people to clean the house, prepare meals, buy groceries, and look after her childrenâenabling her to work, pursue her interests, and come and go as she wanted. The domestic staff made it possible, too, for Ann and Lolo to cultivate their own professional and social circles, which did not necessarily overlap.

dendeng celeng

âdried, jerked wild boar, which Indonesians hunted in the forests when food was scarce. (“I said, âThat's delicious! I love it, Ann,'” the colleague, Felina Pramono, remembered. “She said, âIt was moldy, Felina.'”) Lolo's pay was so paltry, Ann later joked, it would not have covered the cost of cigarettes (which she did not smoke). But Lolo had a brother-in-law, Trisulo, who was a vice president for exploration and production at the Indonesian oil company Pertamina. When Lolo completed his military service, Trisulo, who was married to Lolo's sister, Soewardinah, used his contacts with foreign oil companies doing business in Indonesia, he told me, to help Lolo get a job in the Jakarta office of the Union Oil Company of California. By the early 1970s, Lolo and Ann had moved into a rented house in Matraman, a middle-class area of Central Jakarta near Menteng. The house was a

pavilyun,

an annex on the grounds of a bigger main house, according to a former houseboy named Saman who worked in those years for Lolo and Ann. It extended straight back from the street, perpendicular to the roadway, into a garden. It had three bedrooms, a kitchen, a bathroom, a library, and a terrace. Like the households of other Indonesians who could afford it, and of foreigners living in Indonesia, it had a sizable domestic staff. Two female servants shared a bedroom; two menâa cook and the houseboyâslept mostly on the floor of the house or outside in the garden, according to Saman. The staff freed Ann from domestic obligations to a degree that would have been almost impossible in the United States. There were people to clean the house, prepare meals, buy groceries, and look after her childrenâenabling her to work, pursue her interests, and come and go as she wanted. The domestic staff made it possible, too, for Ann and Lolo to cultivate their own professional and social circles, which did not necessarily overlap.

Lolo (third from left) with the Indonesian border-survey team in Merauke, Irian Barat, July 1967

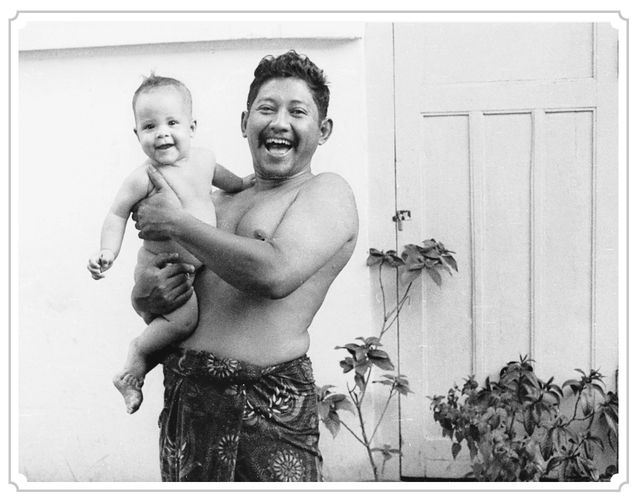

On August 15, 1970, shortly after Barry's ninth birthday and during what would turn out to be Madelyn Dunham's only visit to Indonesia, Ann gave birth to Maya at Saint Carolus Hospital, a Catholic hospital thought by Westerners at that time to be the best in Jakarta. When Halimah Brugger gave birth in the same hospital two years later, she told me, the doctor delivered her baby without the luxury of a stethoscope, gloves, or gown. The doctor, a woman, was wearing a pink suit. “When the baby was born, the doctor asked my husband for his handkerchief,” Brugger remembered. “Then she stuffed it in my mouth and gave me eleven stitches without any anesthesia.”

Lolo and Maya, about 1971

Ann tried out three different names for her new daughter, all of them Sanskrit, before settling on Maya Kassandra. The name was important to Ann, Maya told me; she wanted “beautiful names.” Stanley, it seems, was not on the list.

Ann had wasted no time finding a jobâboth to help support the family and to begin to figure out what she was going to do with her life. By January 1968, she had gone to work as assistant to the American director of Lembaga Indonesia-Amerika, a binational organization funded by the United States Information Service and housed at the U.S. Agency for International Development. Its mission, it said, was promoting cross-cultural friendship. Ann supervised a small group of Indonesians who taught English classes for Indonesian government employees and businessmen being sent by USAID to the United States for graduate studies, said Trusti Jarwadi, one of the teachers Ann supervised. Ann built a small library, stocked largely with textbooks on English grammar and writing, for use by the teachers and students. It would be an understatement to say she disliked the job. “I worked at the U.S. Embassy in Djakarta for 2 horrible years,” she wrote bluntly, with no further details, in a letter in 1973 to her friend from Mercer Island, Bill Byers. As Obama describes the job in his memoir, “The Indonesian businessmen weren't much interested in the niceties of the English language, and several made passes at her. The Americans were mostly older men, careerists in the State Department, the occasional economist or journalist who would mysteriously disappear for months at a time, their affiliation or function in the embassy never quite clear. Some of them were caricatures of the ugly American, prone to making jokes about Indonesians until they found out she was married to one.” Occasionally, she brought Barry to work. Joseph Sigit, an Indonesian who worked as office manager at the time, told me, “Our staff here sometimes made a joke of him because he looked differentâthe color of his skin.”

Joked with himâor about him? I asked.

“With and about him,” Sigit said, with no evident embarrassment.

Ann soon moved on. At age twenty-seven, she was hired to start an English-language, business-communications department in one of the few private nonprofit management-training schools in the country. The Suharto government was embarking on a five-year plan, but Indonesia had few managers with the training to put the new economic policies into practice. The school, called the Institute for Management Education and Development, or Lembaga Pendidikan den Pembinaan Manajemen, had been started several years earlier by a Dutch Jesuit priest, Father A. M. Kadarman, with the intention of helping build an Indonesian elite. It was small, and its courses were oversubscribed. In 1970, the Ford Foundation made the first in a series of grants to the institute to expand the faculty and send teachers abroad for training. At about the same time, Father Kadarman hired Ann, who had found a group of young Americans and Britons enrolled in an intensive course in Bahasa Indonesia, the national language, at the University of Indonesia. “I think she found out about us because she had some connection to the University of Indonesia,” recalled Irwan Holmes, a member of the original group. “She was looking for teachers.” A half-dozen of them accepted her invitation, many of them members of an international spiritual organization, Subud, with a residential compound in a suburb of Jakarta. Ann's new business-communications department offered intensive courses in business English for executives and government ministers. Ann, who may have begun to pick up Bahasa Indonesia from Lolo while she was still in Hawaii and acquired it rapidly once she was in Jakarta, trained the teachers, developed the curriculum, wrote course materials, and taught top executives. In return, she received not a simple paycheck but a share of the revenue from the program. Few Indonesians understood the department's potential, said Felina Pramono, an English teacher from central Java whom Father Kadarman hired as Ann's assistant and soon promoted to teaching. But the program took off. “She was a very clever woman,” Pramono told me. “Young as she was, she was quite mature intellectually.”

Ann became a popular teacher. For many of the students, the classes were at least as much a social activity as they were about serious learning, said Leonard Kibble, who taught part-time at the institute in the early 1970s. They took place in the late afternoon and evening, after the students got off work. Because there was just one miserable state television channel at that time, Kibble said, there was little else to do at that hour. “In such a situation, Indonesians can laugh and joke,” Kibble told me. “They love acting. The teachers had something called ârole simulation'âwhich the students called ârole stimulation.' Some students did very occasionally feel guilty about laughing so much at their fellow students, but that didn't stop them.” Ann's classes in particular “could be a riot of laughter from beginning to end. She had a great sense of humor,” Kibble said. “The laughter in class came not only from Indonesian students making all sorts of funny mistakes trying to speak English but also Ann making all sorts of funny mistakes trying to speak Indonesian.” In one classroom slip that Kibble said Ann delighted in recounting, she tried to tell a student that he would “get a promotion” if he learned English. Instead of using the phrase

naik pangkat

, she said

“naik pantat.”

The word

naik

means to “go up, rise, or mount”;

pangkat

means “rank” or “position.”

Pantat

means “buttocks.”

naik pangkat

, she said

“naik pantat.”

The word

naik

means to “go up, rise, or mount”;

pangkat

means “rank” or “position.”

Pantat

means “buttocks.”

Among the perks of working in the business-English department were the snacks, served in a crowded teachers' lounge during the half-hour break between afternoon and evening classes. In Indonesian, the term

jajan pasar

is used for the ubiquitous homemade snacks sold at food stands and markets.

Pasar

means “market”;

jajan

means “snack.” They include seafood chips, peanut chips, fried chips from the

mlinjo

tree, chips made from ground cowhide mixed with garlic, sweet-potato snacks, mashed cassava snacks, sweet flour dumplings made with sesame seeds, sticky rice flavored with pandanus leaves, sticky black rice sprinkled with grated coconut, and rice cakes wrapped in coconut leaves or banana leaves, to name a few. Some come wrapped in a banana-leaf envelope, ingeniously pinned shut with a wooden toothpick that doubles as a disposable (and biodegradable) utensil. Ann loved Indonesian snacksâat first perhaps simply for the undeniable pleasure of eating them, compounded later by admiration for the enterprising people who made them. At the school, there were sticky rice croquettes,

lemper,

with meat in the middle; rice-flour cookies called

klepon,

with sesame seeds on the outside and palm sugar in the center;

nagasari,

made with bananas, flour, and sugar steamed in a banana leaf; and Dutch cream cakes. The snacks in Ann's department were the envy of other departments. “I think most of us worked there for the really good snacks,” said Kay Ikranagara, an American who met Ann at the school in the early 1970s and became a close friend. Food accompanied every graduation. Felina Pramono and Ann would collaborate on the menu. On one occasion, Pramono ordered a personal favorite, fried brain. Ann instructed her never to order it again.

jajan pasar

is used for the ubiquitous homemade snacks sold at food stands and markets.

Pasar

means “market”;

jajan

means “snack.” They include seafood chips, peanut chips, fried chips from the

mlinjo

tree, chips made from ground cowhide mixed with garlic, sweet-potato snacks, mashed cassava snacks, sweet flour dumplings made with sesame seeds, sticky rice flavored with pandanus leaves, sticky black rice sprinkled with grated coconut, and rice cakes wrapped in coconut leaves or banana leaves, to name a few. Some come wrapped in a banana-leaf envelope, ingeniously pinned shut with a wooden toothpick that doubles as a disposable (and biodegradable) utensil. Ann loved Indonesian snacksâat first perhaps simply for the undeniable pleasure of eating them, compounded later by admiration for the enterprising people who made them. At the school, there were sticky rice croquettes,

lemper,

with meat in the middle; rice-flour cookies called

klepon,

with sesame seeds on the outside and palm sugar in the center;

nagasari,

made with bananas, flour, and sugar steamed in a banana leaf; and Dutch cream cakes. The snacks in Ann's department were the envy of other departments. “I think most of us worked there for the really good snacks,” said Kay Ikranagara, an American who met Ann at the school in the early 1970s and became a close friend. Food accompanied every graduation. Felina Pramono and Ann would collaborate on the menu. On one occasion, Pramono ordered a personal favorite, fried brain. Ann instructed her never to order it again.

Ann was a striking figure who did not go unnoticed. “Maybe just her presenceâthe way she carried herself,” said Halimah Bellows, whom Ann hired in the spring of 1971. She dressed simply, with little or no makeup, and wore her hair long, held back by a headband. By Javanese standards, she was, as Pramono put it, “a bit sturdy for a woman.” She had strong opinionsâand rarely softened them to please others. When she discovered that Irwan Holmes had organized a club in which students would pay to meet at a café and put their English to use in an informal setting, she fired him with no advance warning, he said. “She was obviously very concerned about her business being successful and didn't want anybody moving in on her,” he said. Pramono, a Catholic in a country in which one is asked to identify one's religion in the course of ordinary transactions, such as applying for jobs, felt she detected a mocking quality in Ann's attitude to her religion. “She would just smile and laugh, you know? And a sneer. I could feel it,” Pramono told me. She chose not to be offended, because she liked Ann and believed she would never intentionally hurt anyone. But Pramono made a practice of avoiding the topic of religion. When Kay Ikranagara complained that her students were not working hard enough, Ann told her to stop taking the lessons so seriously and let the students enjoy themselves. They would learn better that way. “She was absolutely right,” Ikranagara said. “But she was not sympathetic: âThis is your problem. . . .'”

Other books

Snow and Mistletoe by Riley, Alexa

The Djinn by Graham Masterton

The Edge of Light by Joan Wolf

Blood Cries Afar by Sean McGlynn

The Island by Bray, Michael

Love & Marry by Campbell, L.K.

Out of the Dark by Patrick Modiano

The Naked Detective by Laurence Shames

Rival Love by Natalie Decker

3013: MATED (3013: The Series) by Roma, Laurie