A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal (35 page)

Read A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal Online

Authors: Michael Preston Diana Preston

Tags: #History, #India, #Architecture

At this early stage in his life Aurangzeb was in high favour. The year after his successful campaign against the Raja of Orchha, Shah Jahan appointed him Governor of the Deccan, a post he would hold for eight years. The presence of Aurangzeb with an enormous army in this still troublesome region was sufficiently threatening to persuade Bijapur’s ruler to sign a treaty with the Moghuls and to induce the ruler of Golconda to make a token submission. In the following years, Shah Jahan promoted Aurangzeb twice more, increasing his rank and his allowances.

In May 1644, learning of the accident that had befallen Jahanara, Aurangzeb had hastened from the Deccan to her bedside in Agra. However, something occurred during this visit that soured his relationship with his father and lost Aurangzeb both his rank and governorship. The historian Lahori says that the prince had fallen

‘under the influence of ill-advised and short-sighted companions’ and ‘had determined to withdraw from worldly occupations’

. However, more specific clues are offered in a bitter letter written by Aurangzeb ten years later to Jahanara in which he stated:

‘I knew my life was a target [of rivals] …’

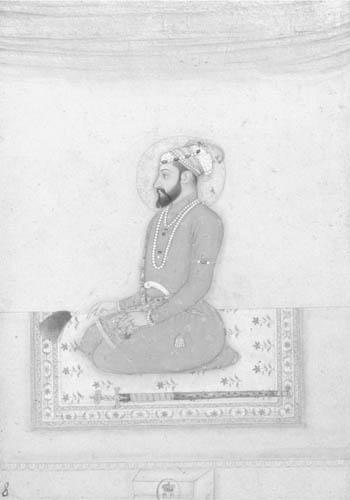

Aurangzeb at prayer

.

The rival Aurangzeb feared but did not name was his handsome, charismatic elder brother, the Sufi-following Dara Shukoh. Dara was frequently by his father’s side, the object of constant signs of his love and affection, and in 1633 Shah Jahan had marked him out as his chosen successor, conferring on him the district of Hissar Firoza, traditionally awarded to the heir apparent, together with the right to pitch a crimson tent. Aurangzeb resented these marks of favour to Dara. As he grew up he also came to disapprove thoroughly of Dara’s wideranging religious interests, which, though they mirrored the tolerance and curiosity of Jahangir and Akbar, smacked to him of heresy. Dara in return disparaged Aurangzeb as a narrow-minded fundamentalist.

According to a courtier the tensions between the two brothers were dramatically and publically exposed during Jahanara’s convalescence when Aurangzeb accompanied his father to inspect Dara’s new riverside mansion in Agra. While they were touring the building, Dara invited Aurangzeb to enter an underground chamber but he refused, convinced that Dara meant to kill him there. Instead, he remained obstinately in the doorway, defying even his father’s order to enter.

This story seems too melodramatic to be true but the suggestion of some kind of showdown is probably valid. Certainly Aurangzeb was jealous of Dara and felt neglected by his father. Unable to contain his feelings any longer he must have complained to his father, but instead of winning Shah Jahan’s sympathy he incurred his anger. In the ensuing row either Shah Jahan stripped him of his rank and office or, as some accounts suggest, Aurangzeb himself resigned his position out of pique.

Whatever the case, Aurangzeb soon regretted the breach, but it took him seven months to regain Shah Jahan’s favour. Even then, as a court historian recorded, this was only

‘due to the urging of his royal sister’

. Jahanara chose the celebrations for her recovery as the moment to make her plea and Shah Jahan indulged her, reinstating Aurangzeb in his former rank and a few months later, in February 1645, appointing him governor of wealthy Gujarat. All appeared well again, but the episode held disturbing echoes of past jealousies within the imperial family, in particular Shah Jahan’s own rivalry with Khusrau. Shah Jahan and Khusrau had, of course, been only half-brothers, while Dara Shukoh and Aurangzeb were full brothers, but over coming years this would count for nothing at all.

*

The

urs

was of course celebrated on the anniversary of Mumtaz’s death according to the Muslim lunar calendar and not the Western solar one.

*

The family weakness for alcohol had clearly been inherited by both Jahanara and her younger sister Raushanara and, as imperial princesses, they were free to indulge it within their private quarters.

13

‘The Sublime Throne’

I

n late 1645 news reached Shah Jahan from Lahore of the death of his ally turned adversary, the sixty-eight-year-old Nur Jahan. The bazaars hummed with lurid rumours of murder but it seems more likely that, as the official histories recorded, she had died of natural causes. Since the death of her husband she had lived the secluded life of a widow with little scope for intrigue, so that Shah Jahan had no cause to order her death. His policy towards Nur had been to ignore her personally and systematically to remove traces of her once pervasive influence, withdrawing from circulation all coins stamped with her name and purging his court of officials once loyal to her. Moghul historians would be divided in their view of her, depending, of course, on their political loyalties. Many deplored her power over Jahangir, but none could disguise her remarkable career, which owed as much to her abilities as Jahangir’s weaknesses.

*

Although the Taj Mahal was largely complete, Shah Jahan absorbed himself in other elaborate, expensive and ambitious building projects. In 1647 he began construction of the exquisite Moti Masjid – the Pearl Mosque – in the Red Fort at Agra. However, he reserved his grandest plans of all for Delhi, building an entire new metropolis – Shahjahanabad (the present city of Old Delhi) – on the west banks of the Jumna. His historian Inayat Khan described his quest for

‘some pleasant site, distinguished by its genial climate, where he might find a splendid fort and delightful edifices … through which streams of water should be made to flow, and the terraces of which should overlook the river’

. As well as desiring to found a city as an expression of his power, Shah Jahan, who found the heat of Hindustan just as oppressive as his forebears, wished to escape Agra’s hot, searing winds and, perhaps, also memories of Mumtaz.

Shah Jahan began work on Shahjahanabad in 1639 and, as with the Taj, progress was swift. An army of labourers, stonecutters, ornamental sculptors, masons and carpenters constructed a massive citadel, the Red Fort, encircled by high sandstone walls with twenty-seven towers and eleven great gates. This new fortress-city was twice the size of the Agra fort. Grand avenues connected the different sectors – the bazaars, administrative offices, courtiers’ residences, the imperial chambers of state and the harem with its pavilions decorated with gold and inlaid jewels.

Fountains and watercourses sparkled throughout. François Bernier marvelled at the urban planning:

‘Nearly every chamber has its reservoir of running water at the door; on every side are gardens, delightful alleys, shady retreats, streams, fountains, grottoes, deep excavations that afford shelter from the sun by day, lofty divans and terraces, on which to sleep coolly at night. Within the walls of this enchanting place no oppressive or inconvenient heat is felt.’

A water channel, the ‘River of Paradise’, flowed past the imperial quarters. As with nearly all Moghul watercourses, the gradient was as shallow as possible – just enough to keep the water moving but imperceptible to the human eye. The main harem building, the Rang Mahal, was a palace of shimmering white marble with, at its four corners, small chambers whose surfaces sparkled with tiny mirrors; but most elegant of all was Shah Jahan’s Hall of Private Audience – an open marble pavilion inlaid with precious stones in floral designs to create a jewelled garden beneath a ceiling of silver and gold.

Ten days of gorgeous ceremonial marked the inauguration of Shahjahanabad. Some 3,000 workers laboured for a month with powerful cranks and hoists to erect in the courtyard of the new fort a giant velvet canopy woven on the looms of Gujarat, embroidered in gold and large enough to shade 10,000 people. On 18 April 1648, at the exact moment deemed favourable by the court astrologers and to the beating of kettledrums, Shah Jahan arrived by royal barge and mounted his Peacock Throne.