A Thursday Next Digital Collection: Novels 1-5 (138 page)

Read A Thursday Next Digital Collection: Novels 1-5 Online

Authors: Jasper Fforde

BOOK: A Thursday Next Digital Collection: Novels 1-5

5.31Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

“But you said . . . ?”

“Yes, Mother, that was an excuse to stop you barging in on Emma and Hamlet.”

“Oh,” she said, realization dawning. “Well, let's have a cup of tea anyway.”

I breathed a sigh of relief, and Mother walked into the kitchenâto find Hamlet and Emma talking as they did the washing up. Mother stopped dead and stared at them.

“It's disgusting!” she said at last.

“Excuse me?” inquired Hamlet.

“What you're doing in the living roomâon

my

sofa.”

my

sofa.”

“What are we doing, Mrs. Next?” asked Emma.

“What are you doing?” flustered my mother, her voice rising. “I'll tell you what you're doing. Well, I won't because it's tooâHere, have a look for yourself.”

And before I could stop her, she opened the door to the living room to revealâFriday, alone, asleep on the sofa.

My mother looked confused and stared at me.

“Thursday, just what is going on?”

“I can't even begin to explain it,” I replied, wondering where Melanie had gone. It's a big room, but not nearly large enough to hide a gorilla. I leaned in and saw that the French windows were ajar. “Must have been a trick of the light.”

“Trick of the light?”

“Yes. May I?”

I closed the door and froze as I noticed Melanie tiptoeing across the lawn, fully visible through the kitchen windows.

“How can it be a trick of the light?”

“I'm . . . not really sure,” I stammered. “Have you changed the curtains in here? They look kind of different.”

“No. Why didn't you want me to look in the living room?”

“Because . . . because . . . I asked Mrs. Beatty to look after Friday, and I knew you didn't approve, but now she's gone and everything is okay.”

“Ah!” said my mother, satisfied at last. I breathed a sigh of relief. I'd got away with it.

“Goodness!” said Hamlet, pointing. “Isn't that a gorilla in the garden?”

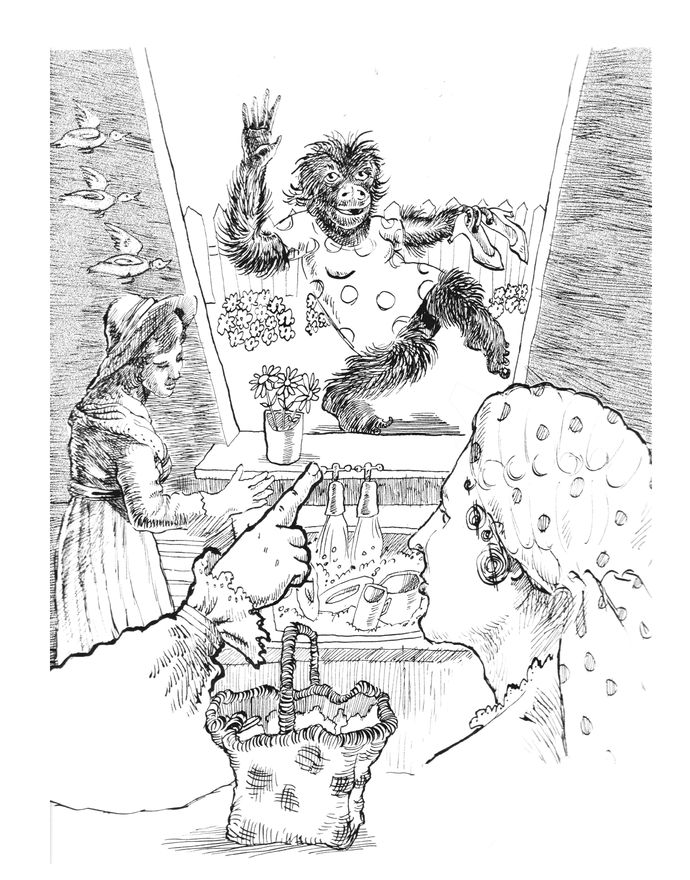

All eyes swiveled outside, where Melanie stopped in midstride over the sweet williams. She paused for a moment, gave an embarrassed smile and waved her hand in greeting.

“Where?” said my mother. “All I can see is an unusually hairy woman tiptoeing through my sweet williams.”

“That's Mrs. Bradshaw,” I murmured, casting an angry glance at Hamlet. “She's been doing some child care for me.”

“Well, don't be so rude and let her wander around the garden, Thursdayâask her in!”

Mum put down her shopping and filled the kettle. “Poor Mrs. Bradshaw must think us dreadfully inhospitable. Do you suppose she'd fancy a slice of Battenberg?”

Hamlet and Emma stared at me, and I shrugged. I beckoned Melanie into the house and introduced her to my mother.

“Pleased to meet you,” said Melanie. “You have a very lovely grandchild.”

“Thank you,” Mum replied, as though the effort had been entirely hers. “I do my best.”

“I've just come back from Trafalgar,” I said, turning to Lady Hamilton. “Dad's restored your husband, and he said he'd pick you up at eight-thirty tomorrow.”

“Oh!” she said, with not quite as much enthusiasm as I had hoped. “That's . . . that's wonderful news.”

“Yes,” added Hamlet more sullenly, “wonderful news.”

They looked at one another.

“I'd better go and pack,” said Emma.

“Yes,” replied Hamlet, “I'll help you.”

And they both left the kitchen.

“What's wrong with them?” asked Melanie, helping herself to a slice of the proffered cake and sitting down on one of the chairs, which creaked ominously.

“Lovesick,” I replied. And I think they genuinely were.

“So, Mrs. Bradshaw,” began my mother, settling into business mode, “I have recently become an agent for some beauty products, many of which are

completely unsuitable

for people who are baldâif you get my meaning.”

completely unsuitable

for people who are baldâif you get my meaning.”

“Ooooh!” exclaimed Melanie, leaning closer. She

did

have a problem with facial hairâhard not to, being a gorillaâand had never had the benefit of talking to a cosmetics consultant. Mum would probably end up trying to sell her some Tupperware, too.

did

have a problem with facial hairâhard not to, being a gorillaâand had never had the benefit of talking to a cosmetics consultant. Mum would probably end up trying to sell her some Tupperware, too.

I went upstairs, where Hamlet and Emma were arguing. She seemed to be saying that her “dear Admiral” needed her more than anything, and Hamlet said that she should come and live with him at Elsinore and “to hell with Ophelia.” Emma replied that this really wasn't practical and then Hamlet made an extremely long and intractable speech which I

think

meant that nothing in the real world was simple or slick and he lamented the day he ever left his play, and that he was sure Ophelia had discussed country matters with Horatio when his back was turned. Then Emma got confused and thought he was impugning

her

Horatio, and when he explained that it was

his

friend Horatio she changed her mind and said she would come with him to Elsinore, but then Hamlet thought perhaps this wasn't such a good idea after all and he made

another

long speech until even Emma got bored and she crept downstairs for a beer and returned before he'd even noticed she had gone. After a while he just talked himself to a standstill without having made any decisionâwhich was just as well as there wasn't a play for him to return to.

think

meant that nothing in the real world was simple or slick and he lamented the day he ever left his play, and that he was sure Ophelia had discussed country matters with Horatio when his back was turned. Then Emma got confused and thought he was impugning

her

Horatio, and when he explained that it was

his

friend Horatio she changed her mind and said she would come with him to Elsinore, but then Hamlet thought perhaps this wasn't such a good idea after all and he made

another

long speech until even Emma got bored and she crept downstairs for a beer and returned before he'd even noticed she had gone. After a while he just talked himself to a standstill without having made any decisionâwhich was just as well as there wasn't a play for him to return to.

. . . Melanie stopped in midstride over the sweet williams. She paused for a moment, gave an embarrassed smile and waved her hand in greeting.

I was just pondering whether finding a cloned Shakespeare was actually going to be possible when I heard a tiny wail. I went back downstairs to find Friday blinking at me from the door to the living room, looking tousled and a little sleepy.

“Sleep well, little man?”

“Sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit,” he replied, which I took to mean, “I have slept very well and now require a snack to see me through the next two hours.”

I walked back into the kitchen, something niggling away at my mind. Something that Mum had said. Something that Stiggins had said. Or maybe Emma? I made Friday a Nutella sandwich, which he proceeded to smear about his face.

“I think you'll find I have just the color for you,” said my mother, picking out a shade of gray varnish that suited Melanie's black fur. “Goodnessâwhat strong nails!”

“I don't dig as much as I used to,” replied Melanie with an air of nostalgia. “Trafford doesn't like it. He thinks it makes the neighbors talk.”

My heart missed a beat, and I shouted out, quite spontaneously, “AHHHHHHHHH!”

My mother jumped and painted a line of nail varnish up Melanie's hand and upset the bottle onto her polka-dot dress.

“Look what you've made me do!” she scolded. Melanie didn't look very happy either.

“Posh, Murray Posh, Daisy Posh, Daisy MutlarâWhy did you . . . mention Daisy Mutlar a few minutes ago?”

“Well, because I thought you'd be annoyed she was still around.”

Daisy Mutlar, it must be understood, was someone whom Landen nearly married during our ten-year enforced separation. But that wasn't important. What

was

important is that without Landen there had never been any Daisy. And if Daisy was around, then Landen must be, tooâ

was

important is that without Landen there had never been any Daisy. And if Daisy was around, then Landen must be, tooâ

I looked down at my hand. On my ring finger was . . . a ring. A

wedding

ring. I pulled it forward to the knuckle to reveal a white ridge. It looked as though it had always been there. And if it had . . .

wedding

ring. I pulled it forward to the knuckle to reveal a white ridge. It looked as though it had always been there. And if it had . . .

“Where's Landen now?”

“At his house, I should imagine,” said my mother. “Are you staying here for supper?”

“Then . . . he's

not

eradicated?”

not

eradicated?”

She looked confused. “Good Lord, no!”

I narrowed my eyes. “Then I didn't ever go to Eradications Anonymous?”

“Of course not, darling. You know that myself and Mrs. Beatty are the only people who ever attendâand Mrs. Beatty is just there to comfort me. What on earth are you talking about? And come back! Where do youâ”

Â

I opened the door and was two paces down the garden path when I remembered I had left Friday behind, so went back to get him, found he had got chocolate all over his front despite the bib, put on his sweatshirt over his T-shirt, found he had glibbed down the front of it, got a clean one, changed his nappy, andâno socks.

“What are you doing, darling?” asked my mother as I rummaged in the laundry basket.

“It's Landen,” I babbled excitedly. “He was eradicated, and now he's back, and it's as though he'd never gone, and I want him to meet Friday, but Friday is way way too sticky right now to meet his father.”

“Eradicated? Landen? When?” asked my mother incredulously. “Are you sure?”

“Isn't that the point about eradication?” I replied, having found six socks, none of them matching. “No one

ever

knows. It might surprise

you

to know that Eradications Anonymous once had forty or more attendees. When I came, there were fewer than ten. You did a wonderful job, Mother. They'd all be really gratefulâif only they could remember.”

ever

knows. It might surprise

you

to know that Eradications Anonymous once had forty or more attendees. When I came, there were fewer than ten. You did a wonderful job, Mother. They'd all be really gratefulâif only they could remember.”

“Oh!” said my mother in a rare moment of complete clarity. “Then . . . when eradicatees are brought back, it was as if they had never gone. Ergo: the past automatically rewrites itself to take into account the noneradication.”

“Well, yesâmore or less.”

I slipped some odd socks on Friday's feetâhe didn't help matters by splaying his toesâthen found his shoes, one of which was under the sofa and the other right on top of the bookcaseâMelanie

had

been climbing on the furniture after all. I found a brush and tidied his hair, trying desperately to get an annoying crusty bit that smelt suspiciously of baked beans to lie flat. It didn't and I gave up, then washed his face, which he didn't like one bit. I eventually managed to make it out of the door when I saw myself in the mirror and dashed back upstairs. I plonked Friday onto the bed, put on a clean pair of jeans and T-shirt and tried to do somethingâ

anything

âwith my short hair.

had

been climbing on the furniture after all. I found a brush and tidied his hair, trying desperately to get an annoying crusty bit that smelt suspiciously of baked beans to lie flat. It didn't and I gave up, then washed his face, which he didn't like one bit. I eventually managed to make it out of the door when I saw myself in the mirror and dashed back upstairs. I plonked Friday onto the bed, put on a clean pair of jeans and T-shirt and tried to do somethingâ

anything

âwith my short hair.

“What do you think?” I asked Friday, who was sitting on the dressing table staring at me.

“Aliquippa ex consequat.”

“I hope that means â You look adorable, Mum.' ”

“Mollit anim est laborum.”

I pulled on my jacket, walked out of my room, came back to brush my teeth and fetch Friday's polar bear, then was out the door again, telling Mum that I might not be back tonight. My heart was still racing as I walked outside, ignored the journalists and popped Friday into the passenger seat of the Speedster, put down the hoodâmight as well arrive in styleâand strapped him in. I put the key in the ignition and thenâ

“Don't drive, Mum.”

Friday

spoke.

I was speechless for a second, hand poised on the ignition.

spoke.

I was speechless for a second, hand poised on the ignition.

“Friday?” I said. “You're talking . . . ?”

And then my heart grew cold. He was looking at me with the most serious look I have ever seen on a two-year-old, before or since. And I knew the reason why. Cindy. It was the day of the second assassination attempt. In all the excitement, I had completely forgotten. I slowly and very carefully took my hands off the key and left it where it was, turn signal blinking, oil and generator warning lights burning. I carefully unstrapped Friday, and then, not wanting to open any of the doors, I climbed carefully out of the open top and took him with me. It was a close call.

“Thanks, baby, I owe youâbut why did you wait until now to say anything?”

He didn't answer, just put his fingers in his mouth and sucked them innocently.

“Strong silent type, eh? Come on, wonder boy, let's call SO-14.”

The police closed the road and the bomb squad arrived twenty minutes later, much to the excitement of the journalists and TV crews. They went live to the networks almost immediately, linking the bomb squad with my new job as the Mallets' manager, filling up any gaps in the story with speculation or, in one case, colorful invention.

The four pounds of explosives had been connected to the starter-motor relay. One more second and Friday and I would have been knocking on the pearly gates. I was jumping up and down with impatience by the time I had given a statement. I didn't tell them this was the second of three assassination attempts, nor did I tell them there would be another attempt at the end of the week. But I wrote it on

my

hand so I wouldn't forget.

my

hand so I wouldn't forget.

“Windowmaker,”

I told them. “Yes, with an

n

âI don't know why. Well, yesâbut sixty-eight if you count Samuel Pring. Reason? Who knows? I was the Thursday Next who changed the ending of

Jane Eyre

. Never read it? Preferred

The Professor

? Never mind. It'll be in my files. No, I'm with SO-27. Victor Analogy. His name's Friday. Two years old. Yes, he's very cute, isn't he? You do? Congratulations. No, I'd love to see the pictures. His aunt? Really? Can I go now?”

I told them. “Yes, with an

n

âI don't know why. Well, yesâbut sixty-eight if you count Samuel Pring. Reason? Who knows? I was the Thursday Next who changed the ending of

Jane Eyre

. Never read it? Preferred

The Professor

? Never mind. It'll be in my files. No, I'm with SO-27. Victor Analogy. His name's Friday. Two years old. Yes, he's very cute, isn't he? You do? Congratulations. No, I'd love to see the pictures. His aunt? Really? Can I go now?”

Other books

City of the Sun by Juliana Maio

New Boy by Julian Houston

The Familiars: Secrets of the Crown by Adam Jay Epstein, Andrew Jacobson

Resilience (Warner's World Book 6) by Dave O'Connor

Tipping Point in the Alliance War by Lefler, Terry

Murder So Sweet: A Frosted Love Cozy Mystery (Frosted Love Mysteries Book 3) by Carol Durand, Summer Prescott

(1964) The Man by Irving Wallace

Privy to the Dead by Sheila Connolly

Kaleidoscope Summer (Samantha's Story) by Garcia, Rita

The Body on the Beach (The Weymouth Trilogy) by Church, Lizzie