A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (10 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

One of the driving forces behind Palmerston’s enmity toward the United States was its refusal to agree to a slave trade treaty. To his mind, the acts abolishing the slave trade in 1807 and then slavery throughout the British Empire in 1833 had joined such other events as the Glorious Revolution and Waterloo in the pantheon of great moments in the nation’s history. For many Britons, the eradication of slavery around the globe was not simply an ideal but an inescapable moral duty, since no other country had the navy or the wealth to see it through. At the beginning of 1841, Palmerston had almost concluded the Quintuple Treaty, which would allow the Royal Navy to search the merchant ships of the Great Powers. “If we succeed,” Palmerston told the House of Commons on April 15, 1841, “we shall have enlisted in this league … every state in Christendom which has a flag that sails on the ocean, with the single exception of the United States of North America.”

9

The Quintuple Treaty was signed, but without the signature of the United States. As a consequence, the slave trade continued exclusively under the American flag. The one concession Britain did obtain—and this was not accomplished by Palmerston, who was out of government between 1841 and 1846—was the formation of joint patrols with the U.S. Navy off the West African coast.

Whether Palmerston was foreign secretary, however, made no difference to the constant wrangling or the relentless expansion of the Union over the lands of Native Americans as well as British-held territories. Three years later, in 1844, the presidential candidate of the Democratic Party, James Polk, ran on a platform that all of Britain’s Oregon territories right up to Russian America should be annexed by the United States. “The only way to treat John Bull is to look him in the eye,” Polk wrote in his diary. “If Congress falters or hesitates in their course, John Bull will immediately become arrogant and more grasping in his demands.”

10

Polk’s claim for all the land as far as what is now southern Alaska resulted in the popular slogan “Fifty-four Forty or Fight!” (meaning that the new boundary line should be drawn along the 54°40’ parallel). But the expected fight never occurred; Texas joined the Union as a slave state in 1845, and a year later President Polk declared war on Mexico, a far less dangerous opponent. The British foreign secretary, Lord Aberdeen, who shied away from gunboat diplomacy, was willing to negotiate, and the Oregon Treaty was signed in June 1846, giving all of present-day Washington, Oregon, and Idaho to the United States.

11

Victory in the Mexican-American War in 1848 resulted in the United States acquiring a further 600 million acres, most of them below the Mason-Dixon Line. There were now thirty states in the Union, once again in an even split between slave and free.

In 1848, the discovery of gold in California led to a rush of settlers—more than eighty thousand of them in a matter of months—and the urgent need to accept the newly acquired territory as the thirty-first state so that law and order could be imposed. But the Southern states would not agree to the addition (since the Californians were demanding to be admitted as a free state) until they had secured a series of concessions. The most bitterly contested of these was the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which allowed “owners” to pursue and recapture their escaped “property” in whatever state he or she happened to be hiding. Graphic newspaper reports—of families torn apart, of law-abiding blacks dragged in chains back to their erstwhile masters—raised an outcry in the North. Several Northern states passed personal liberty laws to try to circumvent the act; in some towns, there was violent resistance to the federal agents who arrived in search of fugitive slaves; and the “underground railroad,” with its vast network of safe houses from Louisiana to the Canadian border, received many more volunteers.

—

The domestic and political turbulence during 1850 was one of the reasons why the United States’ pavilion at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 displayed so few objects compared to those of other nations. The suspicion among Americans that Britain had put on the exhibition simply to show off its status as the richest country in the world had also diminished enthusiasm for taking part. Yet even with a fraction of the exhibits presented by the Great Powers, the American pavilion still won 5 of the 170 Council medals (admittedly, France won 56). The American photography contingent, led by Mathew Brady, won first, second, and third prize.

1.5

The great number of American tourists and businessmen who visited the exhibition brought more contact between the citizens of the two countries than at any other time during the century. Britons now realized the extent to which the United States had developed separately from the mother country. Americans not only had different accents and wore different fashions; their choice of words and phrases sounded quite foreign. They said “I guess” instead of “I suppose,” and “Let’s skedaddle” instead of “Shall we go,” and they called con men “shysters,” an epithet entirely new to English ears.

12

It was their strange and different mannerisms that inspired Tom Taylor to compose

Our American Cousin.

Taylor also wrote the popular 1852 stage version of the novel

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

by Harriet Beecher Stowe. The English took to heart the story of the saintly slave whose goodness and humanity upstage a succession of masters until his murder by the evil Simon Legree. In 1852, its first year of publication, the book sold a million copies in Britain—compared to 300,000 in the United States.

13

Every respectable British household owned a copy.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

was allegedly the first novel Lord Palmerston had read in thirty years, and whether it was the effects of the long abstinence or the allure of the book, he read it from cover to cover three times.

14

The depressing and grisly portrayal of slavery in

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

articulated what the British had long suspected was the truth—despite the South’s self-depiction as an agrarian paradise of courtly manners, charming plantations, and contented slaves. Few Britons had ever seen how slaves really lived, unlike the celebrated British actress Fanny Kemble, whose marriage to Pierce Butler, a Southern slave owner, fell apart after they moved to his Georgia plantation in 1838. They divorced acrimoniously in 1849, with Butler holding Fanny’s daughters hostage until they turned twenty-one.

The publication of

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

led to a renaissance of antislavery clubs in Britain, after they had tottered along in a state of earnest torpor since 1833. The public agitated for Britain “to do something.” In November 1852, Harriet, Duchess of Sutherland, and the Earl of Shaftesbury drafted a petition to “the Women of the United States of America,” urging them to “raise your voices” against slavery. More than half a million British women signed their names to the public letter, which was known as the Stafford House Address. Predictably, the American response was one of outrage.

15

Julia Tyler, the wife of former president John Tyler, led the barrage of scathing replies to “The Duchess of Sutherland and the Ladies of England.” British labor conditions, rigid class structure, and lack of opportunity for self-betterment all came under attack. But it could not be denied that Britain possessed the moral high ground on the issue of slavery. American abolitionists who visited England were amazed to discover that British blacks enjoyed the same rights as their white peers. “We found none of that prejudice against color in England which is so inveterate among the American people,” Elizabeth Cady Stanton had written about her honeymoon in Britain during the summer of 1840. “At my first dinner in England I found myself beside a gentleman from Jamaica, as black as the ace of spades.”

16

Similarly, a former slave, the author Harriet Jacobs, recalled how her self-esteem had changed after visiting England. “For the first time in my life,” she wrote, “I was in a place where I was treated according to my deportment, without reference to my complexion. I felt as if a great millstone had been lifted from my breast.”

17

The Stafford House Address had been doomed to fail no matter how good and sincere its intentions. The Anglophobia that was so often articulated in the U.S. Congress was no more than a reflection of public opinion. Alexis de Tocqueville commented in

Democracy in America

in 1835 that he had never encountered hatred more poisonous than that which Americans felt for England.

18

There were notable exceptions, of course. In the early 1840s the American minister in London told a wildly receptive audience that “the roots of our history run into the soil of England.… For every purpose but that of political jurisdiction we are one people.”

19

But there had existed a deep-rooted prejudice since the War of Independence. The influx of a million Irish refugees during the potato famine merely added more venom to the mix. “Why,” wrote a nineteenth-century American journalist, “does America hate England?” He answered: “Americans believe that England dreads their growing power, and is envious of their prosperity. They detest and hate England accordingly. They have ‘licked’ her twice and can ‘lick’ her again.”

20

Tocqueville attributed the hostility to fifty years of self-congratulatory propaganda. He thought Americans were convinced that their country was a beacon of light to the world; “that they are the only religious, enlightened, and free people … hence they conceive a high opinion of their superiority and are not very remote from believing themselves to be a distinct species of mankind.” The more the English scoffed at this view, the more furious and resentful Americans became toward Britain. The most memorable attack on American exceptionalism was Sydney Smith’s scornful comparison of the two cultures in 1820. “Who reads an American book?” he wrote in the

Edinburgh Review:

Or goes to an American play? Or looks at an American picture or statue? What does the world yet owe to American physicians or surgeons? Who drinks out of American glasses? Or eats from American plates? Or wears American coats or gowns? Or sleeps in American blankets? Finally, under which of the old tyrannical governments of Europe is every sixth man a slave whom his fellow-creatures may buy and sell and torture?

21

A decade later, Fanny Trollope, the novelist and mother of Anthony Trollope, rekindled the impression that all Britons looked down their noses at the former colonists with her book

Domestic Manners of the Americans.

Mrs. Trollope had spent a brief and unhappy period in Ohio in the late 1820s, trying to build a commercial business, which had ended with the family becoming bankrupt and homeless. Her book was not meant to be a serious study of America, but a piece of entertainment to help solve her family’s financial difficulties. While not condemning all Americans in all areas of life, she portrayed the majority as too vulgar, violent, and vainglorious to be really likable. Her view of America inspired hundreds of English imitators, further souring cultural relations between the two countries.

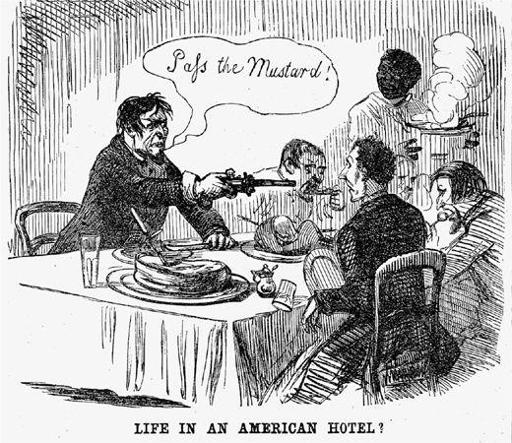

Ill.3

Punch’s view of American manners, 1856.

Other British writers sneered that the self-styled “superior” United States was militarily weak, politically corrupt, and financially unsound.

22

America’s markets were prone to panics; its people preached equality but practiced “mobocracy.” English travelers who saw American democracy in action either condemned it outright or praised it halfheartedly as an evolving system. The greatest blow to American pride came from Charles Dickens. Until his visit to the country in 1842, Americans had considered the world’s bestselling novelist to be almost an adopted son. His humble beginnings and liberal politics had fostered their assumption that the United States would be far more congenial to him than class-ridden England. Dickens had indeed wanted to admire America during his triumphant lecture tour. “Still it is of no use,” he wrote dolefully to a friend during the tour. “I

am

disappointed. This is not the republic I came to see; this is not the republic of my imagination.” He warmed to the friendliness and generosity of its people, and he admired the emphasis on education and public philanthropy. But he found American society as a whole utterly intolerant of dissenting views. “Freedom of opinion! Where is it?” he asked rhetorically after being warned not to discuss the slave mutiny on board the

Creole

outside abolitionist circles, even though the subject was dominating British-American relations.

1.6

If American democracy was simply a vehicle for majority rule, then, asserted Dickens, “I infinitely prefer a liberal monarchy.”

23

He gave vent to his disenchantment in

American Notes,

published in 1842, and

Martin Chuzzlewit,

which followed the year after.