A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (101 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

—

Henry Yates Thompson arrived at Bridgeport, Alabama, forty-seven miles downstream from Chattanooga, on Friday, November 20, carrying a letter of introduction from Edward Everett to Dr. John Newberry, the head of the Western Department of the Sanitary Commission. It was late, so instead of continuing his journey to the commission’s headquarters, Thompson bedded down in one of their tents at Bridgeport. “Before I went to sleep,” he wrote, “I heard a solemn thudding sound outside. I asked my companion what was it and he said: ‘Oh, the last of Sherman’s men crossing the pontoons.’ ”

25

Grant had been waiting for Sherman’s troops to arrive before he made his attack against General Bragg. By November 21 he had accumulated more than sixty thousand men. Staring down at them from Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge was a diminishing army of 33,000 Confederates. The “Cracker Line” had answered the Federal hunger pains, but no such relief had come to Bragg’s army. “Never in all my whole life do I remember of ever experiencing so much oppression and humiliation,” wrote the Confederate private Sam Watkins. “The soldiers were starved and almost naked, and covered all over with lice and camp itch and filth and dirt. The men looked sick, hollow-eyed, and heart-broken, living principally upon parched corn, which had been picked out of the mud and dirt under the feet of officers’ horses.”

26

Thompson and Dr. Newberry boarded a steamboat for the last leg of the journey. It was another two days of arduous travel before they reached Chattanooga on November 22. That day, Bragg stacked the cards against himself still higher by sending two more divisions to Knoxville. “I had a fine view of the whole Rebel position on Missionary Ridge about three miles distant across a wooded valley,” wrote Thompson on the twenty-third:

The pickets and the skirmishers of both sides were behind their respective rifle pits in the valley below us and the Rebel pickets were plainly visible from Fort Wood, about half a mile from where I stood. All those round me were expecting immediate fighting. Soon I saw a sight I shall never forget. The whole Union army in the town—about 25,000 men under General Thomas—left their tents and huts and marched out past Fort Wood in long winding columns creeping into the valley and into line of battle round the town. From Fort Wood it all looked like a great review. But it was in deadly earnest.

Thompson was observing Grant’s test of Bragg’s resolve, to see whether the Confederate general was prepared to fight over Chattanooga or was planning to withdraw. The Union line charged toward Orchard Knob, a fortified hillock at the base of Missionary Ridge. The Confederates in the rifle pits, as mesmerized as Thompson by the bright spectacle rushing toward them, fled. Federal private Robert Neve was surprised to take the hill so easily: “We kept rushing on until we got in sight of their works, which we took with little opposition, and captured a number of prisoners. I took two myself,” he added. Thompson watched as the prisoners were brought in and noticed that they were “rough and ragged men with no vestige of a uniform.” During the night, while Neve lay shivering on the ground listening to every rustle and snap, Thompson rolled bandages for the Sisters of Mercy. He had not expected so much noise or, perhaps, so much blood. “This is war with a vengeance,” he wrote.

27

The men had seemed universally brave and determined. Robert Neve could have enlightened him that nothing was ever uniform in battle: “I noticed in this fight that several officers and men got sheltered behind the trees, and kept waving their hats and cheering men up to a great degree, not even caring about firing a shot at the enemy.”

28

After breakfast on November 24, Thompson returned to Fort Wood to watch the second day of the Battle of Chattanooga. Bragg had managed to recall one of the two divisions sent to Knoxville—General Patrick Cleburne’s—and had placed it at the far end of Missionary Ridge to shore up his right. Grant’s overall plan for the day was simple: to capture the extreme ends of Bragg’s position and then take the middle. “Fighting Joe” Hooker’s day had come.

I began to think nothing was doing [wrote Thompson] when at about midday, when I was dividing my lunch with one of the gunners on the fort, heavy reports of cannon and musketry from Lookout Valley made all of us hurry to that side of Fort Wood. I joined two officers looking through telescopes towards Lookout Mountain and we soon saw Hooker attacking, his men plainly visible to us sweeping round the steep face of Lookout.

Close by me was General Grant in a black surtout with black braid on and quite loose, black trousers and a black wideawake hat and thin Wellington boots. He looked clean and gentlemanly but not military having a Stoop and a full reddish beard, the moustache much lighter than the ends which were trained to a peak.

We saw Hooker’s men fall back once—then they advanced again. After some little suspense we saw the Rebels run round the face of Lookout near the top and Hooker’s line advance after them, rifles popping all along the face of the mountain and guns shelling the retreating Rebels from Moccasin Point and Fort Negley. An officer beside me with a telescope cried out: “There they are and the Rebels are running.” His glass was pointed to the steep face of Lookout more than half way up—and there sure enough, just three miles from us along the sparsely wooded face of the mountain, we saw a running fight with the Rebels retreating before Hooker’s men.

When Hooker’s men planted that large U.S. flag near the top of the mountain, the whole of the troops, and the people in and around Chattanooga, who must number some 60,000 at least, seemed to hurrah together.

The only man who seemed unmoved was General Grant himself, the prime author of all this hurly burly. There he stood in his plain citizen’s clothes looking through his double field-glasses apparently totally unmoved. I stood within a few feet of him and I could hardly believe that here was this famous commander, the model, as it seemed to me, of a modest and homely but efficient Yankee general. I stood next to General Grant for quite some time. If the battle had been a pageant got up for my benefit I could not have had it better.

29

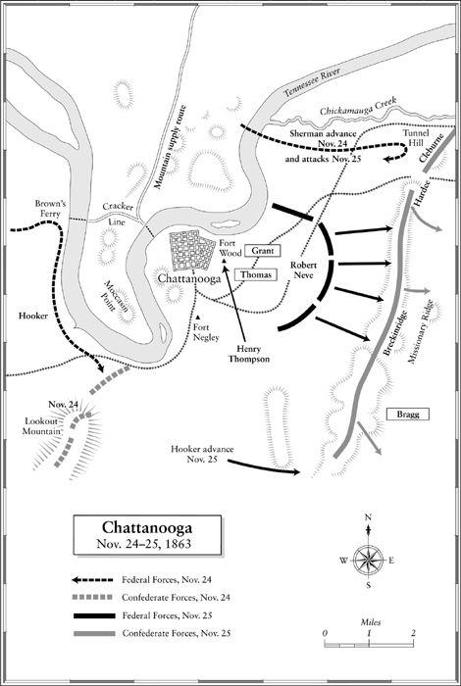

Map.18

Chattanooga, November 24–25, 1863

Click

here

to view a larger image.

Thompson had witnessed the “Battle Above the Clouds,” so called because a light fog had formed on parts of the mountain during the fight, obscuring the valley below. Hooker’s victory had been achieved with surprisingly little cost; his casualties, including those missing and captured, were fewer than two thousand. The following day, the twenty-fifth, was supposed to be Sherman’s turn for glory. Grant expected his man, who had served him so well at Vicksburg, to complete the rout and drive the Confederates off Missionary Ridge. But Sherman’s adversary was General Patrick Cleburne, a former corporal in the 41st (Welsh) Regiment of Foot, who was the best commander in the Army of Tennessee. Cleburne’s new British volunteer aide-de-camp, Captain Charles H. Byrne, who had accompanied Ross and Vizetelly on their journey from Charleston in September, described the fight for his friends. “Three times did they charge our position, and three times were they repulsed,” he wrote. “The third charge was the most determined of the lot. They managed to reach the crest of the hill, and there they fought us for about two hours at a distance varying from twenty to thirty paces;—so close were they that our officers threw stones.”

30

Byrne’s horse was shot in the neck. Rather than abandon his comrades, he chose to remain and fight on foot.

The bravery and sacrifice of Cleburne’s soldiers became immaterial after Grant exploited the fact that Bragg had allowed the center of the Confederate line to thin dangerously during the fight to only fifteen thousand men. At Gettysburg, the Confederate charge at Meade’s center had proved fatal because Lee had failed to dent the Federal strength; but here there was a genuine weakness and Grant prevailed. General Thomas’s division of twenty-five thousand rose from the base of Orchard Knob and smashed through the Confederate defenses at the top of the Ridge. No one had ordered the men to go that far; rage and madness simply took hold of them. “We had all got mixed up,” wrote Robert Neve. “Every man done as he liked, firing to the best advantage until we got twenty yards from the top. Someone cried out, ‘Fix bayonets!’ and ‘Forward to the charge.’ ” The Confederates ran, “leaving cannon, wagons, horses, tools and everything. It was a perfect rout.”

26.2

31

Four thousand Confederates were captured on the Ridge, twice the number of casualties for the battle.

Bragg was powerless to halt the men as they came hurtling down the other side of the mountain toward Ringgold. Sam Watkins saw him ride. “Bragg looked scared. He had put spurs to his horse, and was running like a scared dog.… Poor fellow, he looked so hacked and whipped and mortified and chagrined at defeat, and all along the line, when Bragg would pass, the soldiers would raise the yell, …‘Bully for Bragg, he’s hell on retreat.’ ”

32

The only division that did not panic was Cleburne’s, which held off the Federals long enough to enable the bulk of Bragg’s army to escape off the mountain. The Confederates managed to stay ahead of their pursuers, crossing through Ringgold Gap into Georgia toward the station town of Dalton. Grant did not have the wagons and supplies for an incursion into enemy country, and he forbade his generals to pursue the Confederates past Ringgold.

Henry Yates Thompson explored Bragg’s deserted headquarters two days after the battle, on November 27. Since the twenty-fifth he had been helping Dr. Newberry by identifying the dead and pinning their names to their jackets. The first slain Federal he found turned out to be named John Bull. As Thompson wandered among the bullet-scarred trees, picking up souvenirs, he stumbled across a pile of bodies. He had not noticed them at first because their faded uniforms were the same color as the leaves. They had no hats or shoes.

I went on to a knoll commanding the ridge in both directions [he wrote]. I found two Rebels—one dead and one just alive unattended since the battle. I gave the wounded man what brandy I had left in my flask and he spoke a little. His brains were protruding—the wound was in the back of his head. He seemed thankful for the brandy. I minced and mixed some meat, onions and biscuit and put water with them. He tried to eat but could not chew. A Federal came to help and washed his face.

While combing through the field, Thompson had a second shock. He saw two children, a little girl and boy, scavenging among the dead. They were collecting bullets. “The little girl said she lived ‘over there,’ pointing to Bragg’s headquarters. She had been in the house all through the battle,” he wrote. No one seemed to be responsible for them. The children seemed unaware of the danger that had passed over their heads, or of the perilous future that awaited them once the soldiers were no longer around to share their rations.

33

The pageantry Thompson had seen from afar had darkened to a scene of gore and horror. “The impression left on me by my walks the next day through those blood-stained woods,” he wrote later, “fixed a conviction in my mind, a conviction of the absolute and essential wickedness of those who talk lightly of war and still more of those who lightly begin a war.”

34

Thompson was ready to return home. “Now I am tired to death,” he wrote. His ship was not leaving until December 23, but Thompson felt he had witnessed enough suffering and intended to spend the final weeks of his stay in America visiting friends and enjoying himself as a tourist. His opinion of the North had grown higher still now that he understood the great suffering endured by its people.

—

“God be praised for this victory, which looks like the heaviest blow the country has yet dealt at rebellion,” George Templeton Strong wrote in New York after hearing the news from Chattanooga. “Meade’s army again reported in motion and across the Rapidan,” he added to his diary entry. “The nation needs one or two splendid victories by its Eastern armies to offset those gained in the West.”

35

Two days later, on November 29, General Longstreet received a wire from Jefferson Davis confirming the Confederate defeat at Chattanooga and ordering him to abandon his siege at Knoxville so that he could provide support to Bragg. The telegram had come an hour too late for eight hundred Confederate and thirteen Federal soldiers. One of the worst-planned assaults of the war had just taken place in front of Burnside’s defenses. Francis Dawson was so sickened by the fiasco that he could not bear to write about it in his memoir. All he could say about the twenty minutes of slaughter was that Longstreet’s attack “failed utterly.”