A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (99 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Most Southerners did not believe that British residents were suffering at all. Southern newspapers rarely, if ever, reported when Britons were chained to wagons and dragged through towns to encourage “volunteering,” or hung upside down and repeatedly dunked in water, or threatened with being shot through the knees.

48

25.1

The Confederates loved this song, which Vizetelly composed himself: “ ’Twas in the Atlantic Ocean in the equinoctial gales; / A sailor he fell overboard, amid the sharks and whales. / And in the midnight watch his ghost appeared unto me; / Saying I’m married to a mermaid in the bottom of the sea. CHORUS: Singing Rule Britannia! Britannia rule the waves. / Britons never, never, never will be slaves.”

25.2

When HMS

Virago

eventually made it through to Mobile in January 1864, Consul Cridland told the captain that he had not heard from the Foreign Office for six months. Later, in April, a pathetic message from Consul Lynn miraculously arrived in Washington, begging for guidance: “If I am however, to remain at my post it would afford me sincere gratification if Your Lordship would direct me what course to pursue.” The consuls in the South could not know of the extraordinary efforts made by the Foreign Office in trying to reach them. Lyons pleaded unsuccessfully with Seward to allow a special envoy through the blockade so that Britain could make a direct protest to the Confederate government.

TWENTY-SIX

Can the Nation Endure?

Jefferson Davis’s choice—Saved by the “Cracker Line”—Lincoln addresses the country—Fighting in the clouds—The center breaks—The South holds

F

rancis Lawley had been so sure that Jefferson Davis would dismiss General Bragg that in his

Times

dispatch on October 8, 1863, he wrote as though an announcement was imminent. Yet Bragg’s removal was not preordained. The Battle of Chickamauga had been a stunning victory for the South—the only one since Chancellorsville in May. Longstreet had complained to the secretary of war, James Seddon, “that nothing but the hand of God can help as long as we have our present commander,” without reflecting how his doom-laden letter would appear to the world beyond Tennessee and Georgia. To Davis, the charge seemed self-serving and melodramatic; he agreed with Bragg that it would have been impossible for his shattered army to chase after Union general William Rosecrans even for the ten miles to Chattanooga. Furthermore, aside from the obvious dangers presented by the Confederates’ internal disputes, the Army of Tennessee looked not only secure but on the verge of another success.

Chattanooga was not quite a one-horse town, but with few more than two thousand residents it certainly did not have the resources to feed and shelter an army of more than fifty thousand. The Tennessee River looped the town in a U-bend on three sides, with the fourth, which faced south, overlooked by an undulating chain of mountains. At the southwestern end rose Lookout Mountain, which towered two thousand feet above the town; toward the northeastern end, the six-mile-long Missionary Ridge gently curved around like a natural amphitheater. Since Bragg held both these high points and the railroads in the valley, the Federals’ only safe supply route was a single road through the backcountry that eventually reached Chattanooga via the far side of the Tennessee River. During the rainy season, which was just beginning, the road was expected to become an impassable mud track, leading to inevitable starvation for the Federals.

President Davis had already demonstrated his willingness to be firm with generals who opposed him. Despite public criticism he had shunted aside both Joe Johnston and Pierre Beauregard. But with Braxton Bragg, a man he liked and trusted, Davis was strangely protective. Not even the shocking number of Confederate casualties at Chickamauga—higher than those suffered by Lee at Gettysburg and far higher than those suffered by Rosecrans—shook Davis’s faith in him. After allowing the unhappy generals to air their objections for a couple of days, Davis climbed atop the appropriately named “Pulpit Rock” on Lookout Mountain and made a brief but spirited defense of Bragg to the Confederate troops assembled below, warning his listeners that “he who sows the seeds of discontent and distrust prepares for the harvest of slaughter and defeat.” Davis may have felt that there was no other credible alternative to General Bragg, but the Army of Tennessee disagreed. When Davis boarded his return train on October 14, 1863, much of the army’s will to fight went with him. Instead of giving him three cheers, soldiers shouted, “Send us something to eat, Massa Jeff! I’m hungry! I’m hungry!” (Bragg’s ability to manage the supply operations for the army was no better than his skills as a leader of men.) The news of Davis’s decision spread so quickly that two days later, Consul Cridland wrote to Lord Russell from Mobile, Alabama, that everyone was in despair because President Davis was “retaining General Bragg in command against all opposition.”

1

Bragg’s retribution was swift. The leading rebels found themselves sidelined or dismissed; Longstreet’s command was reduced to the fifteen thousand soldiers who had accompanied him from Virginia, and he was sent to guard Lookout Mountain, as far away from Bragg as possible.

Lawley, Vizetelly, and Ross stayed with Longstreet for another week, loyally enduring the short rations and incessant rain until they could stand it no longer. Vizetelly completed a couple more sketches and Lawley one more dispatch, this time not even trying to sugar over his contempt for Bragg. There was no compelling reason for them to remain, but leaving proved more difficult than they expected, as the few trains running from Chickamauga were reserved for the sick and wounded. Ross solved their problems by making friends with the stationmaster, who retained a proud memory of being inspected by Lord John Russell at the beginning of the war. At first “I tried to explain that he might be mistaken,” wrote Ross, who realized that the man had confused Lord Russell with William Howard Russell. Since the stationmaster found them room in a covered wagon (which let in the rain only at the corners), he decided to drop the point.

2

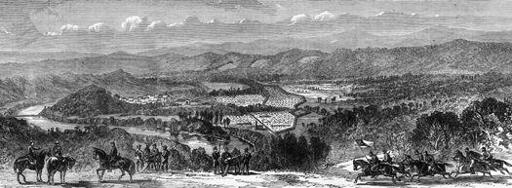

Ill.47

Chattanooga and the Federal lines from the lower ridge of Lookout Mountain, by Frank Vizetelly.

They arrived back in Augusta, Georgia, two days later, on October 24. To their relief, the Planters Hotel had rooms for all of them. “A clean bed with actual sheets,” exclaimed Lawley, “plenty of water to wash in, decent food, a table to write on, candles”—these were luxuries to a man “who has long floundered in the mud of General Bragg’s camp.”

3

The weather was less harsh, too, and a gentle autumn wind replaced the cruel downpours of Tennessee. The men passed the afternoons on their hotel balcony in shirtsleeves, smoking and chatting. They tried out the local theater and discovered it to be quite passable. Vizetelly’s only complaint was the tea served at the Planters, which was so weak he wondered how it managed to reach the spout.

4

Little news filtered down to Augusta from Bragg’s camp, and certainly none from the besieged Federals in Chattanooga. The three friends were unaware that Washington had sent 23,000 troops from the Army of the Potomac to reinforce Rosecrans. Lincoln had acted decisively; there was only one general he truly believed in, and he called upon him now. Ulysses S. Grant was summoned from his headquarters in Cairo, Illinois, and ordered to Chattanooga. Lincoln had written to Grant after Vicksburg, “When you turned northward, east of the Big Black, I feared it was a mistake. I now wish to make the personal acknowledgement that you were right and I was wrong.”

5

The president showed his newfound faith in Grant by placing him in overall command of the three main Federal armies in the west.

Lincoln was taking a risk by interfering with the Army of the Cumberland. “Old Rosy,” as the soldiers called Rosecrans, remained beloved by the men; he had meticulously looked after their welfare, and many of them were sorry to see him dismissed. “Worst of all,” wrote the English volunteer Robert Neve of the 5th Kentucky Volunteers, worse than the short rations, lack of blankets, and leaking tents, “was the order for General Rosecrans to be relieved. It was read to us on parade.”

6

Rosecrans’s popularity with the soldiers was the chief reason why Lincoln waited until after the election for state governor in Ohio on October 13 to dismiss him, fearing that to do otherwise could push the soldier vote toward Vallandigham (who lost by a wide margin). But once the election was out of the way, he agreed that General Rosecrans could be replaced by the “Rock of Chickamauga,” General George Thomas, who had prevented a complete Federal rout at that battle.

The Confederate siege of Chattanooga was so tight that after a mere three weeks, sutlers in the town were charging six cents for a mouthful of bread—the usual price for two loaves. In the animal pens, the horses and mules were staggering in the last throes of starvation. Every building in the town had been transformed into makeshift hospitals, except for the Catholic church where Rosecrans worshipped. Grant arrived at Chattanooga on October 23, still using crutches after a fall from his horse in August. But the painful injury had not affected his vigor or determination. The 23,000 reinforcements from Virginia had arrived, led by a chastened “Fighting Joe” Hooker. General Sherman’s corps was coming from Mississippi. Grant was confident he could best his opponent; the real enemy he feared was Tennessee’s geography. Somehow he had to ferry food and grain to Chattanooga before the entire Army of the Cumberland collapsed or surrendered.

If Rosecrans had at least been able to hold on to Lookout Mountain, the situation facing the Federals would not have been so dire. With the Confederates now in possession of it, all the southern routes into the town, including the river, roads, and railway, were exposed to enemy fire. But the engineers of the Army of the Cumberland had come up with a plan. It required a furtive night expedition along the Tennessee River, beneath the Confederate guns on Lookout Mountain. If successful, they would be able to build a pontoon bridge two miles upriver, where a bend in the river would put the Federal forces beyond the reach of artillery fire.

At 3:00

A.M.

on October 27, fifty pontoon boats, each carrying twenty-four soldiers and two rowers, silently paddled past the Confederates. Robert Neve was in the fourth boat. “It was a fine moonlit night and very still,” he wrote. “We passed down very quiet and could even see the Rebel pickets standing before their fires. It did not create any alarm.”

7

They seized the landing with relative ease, driving back a small Confederate counterattack with few losses. “The next job was to cut down all trees … all day long we had to work felling trees and making small breastworks. Here we were all but starving. Rations were very short.” A Confederate attack was expected, and it came at midnight on the twenty-eighth. This should have been Longstreet’s second triumph at Chattanooga, his opportunity to defeat Grant without having to engage in a major battle. But Longstreet had not been paying attention to the Federal inroads along the southern end of the valley, and he made a serious mistake now by sending only four brigades against the attack force. The Confederates were easily overwhelmed and had to retreat back up Lookout Mountain.

The next day, the first supply wagons carrying hardtack (called “crackers” by the army) and dried beef came rolling through along the “Cracker Line.” The route stretched back for hundreds of miles. In northern Kentucky, a partially restored Ebenezer Wells led a wagon train of more than two thousand pack animals, fighting fever and exhaustion to keep the supplies moving. Robert Neve soon noticed the difference in his rations. Over the next two weeks more supplies arrived, including fresh vegetables and new uniforms. “Our rations were getting better, and we felt better as well.” His regiment was so close to the Confederate pickets that they agreed to take turns on picket duty. “We would wave each other’s caps and then exchange newspapers.” The reversal of their fortunes was complete; it was now the Confederates who were outnumbered, starving, and miserable and the Federals who were growing in confidence and strength.

General Bragg grasped the magnitude of Longstreet’s mistake in failing to prevent the Federal bridgehead into Chattanooga, but his reaction to the disaster was perverse. Instead of trying to plug the gap or reinforce his position, Bragg chose to send Longstreet away, along with twenty thousand men, on an expedition to take Knoxville, Tennessee, from General Burnside. There was some rationale to the decision: if Burnside could be forced back to central Tennessee, the Confederates would repossess the three railways that passed through Knoxville and the all-important Cumberland Gap, which would restore the quick route to Virginia. But at best the mission was a dangerous sideshow when Federal supplies and troops were pouring into Chattanooga.