A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (103 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Two weeks after Lawley left for England, Vizetelly realized that he, too, was exhausted and should return home to rest before the fighting resumed in the spring. In his last dispatch from the South, Vizetelly admitted that his two years in the Confederacy had affected him more than any other assignment; “every soldier of the army of Northern Virginia was a comrade. We had marched many weary miles together, and I had shared in some of their dangers,” he wrote. “This brought me nearer to them than years of ordinary contact could have done.” As he rode away from Jeb Stuart’s camp in late January, Vizetelly stopped to look back at the little gathering of tents, suddenly afraid for “the many friends who were lying there, some of whom would breathe their last in the first glad sunshine of [the] coming spring.”

6

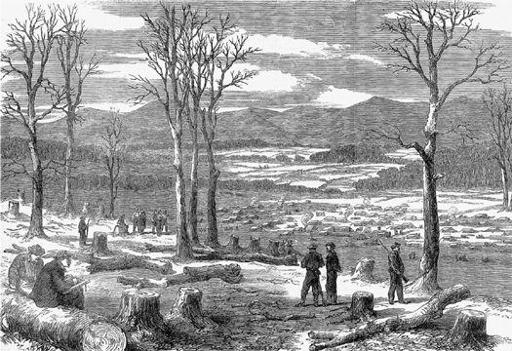

Ill.48

Winter quarters of Jeb Stuart’s cavalry, by Frank Vizetelly, who sketches himself on the left.

—

As Lawley and Vizetelly made their separate journeys across the Atlantic, each having run the blockade at Wilmington, news of CSS

Alabama

’s latest raids on Northern ships was spreading. Captain Raphael Semmes daily expected to see a Federal fleet bearing down on the

Alabama,

but none came. “My ship had been constantly reported, and any one of his clerks could have plotted my track … so as to show [Gideon Welles] where I was bound.” Instead, laughed Semmes, the U.S. navy secretary played an endless and unwinnable game of chase. All Semmes had to do was estimate how long it would take for intelligence of his whereabouts to reach Washington and make sure he left ahead of his pursuers.

7

Since the Confederate commerce raider’s launch in 1862, Semmes had burned or released on bond forty-two vessels, sunk the gunboat USS

Hatteras

at Galveston, and converted one captured vessel into a satellite raider (the

Tuscaloosa

would have a short career of six months and take only one prize). But by the summer of 1863 the

Alabama

and its crew were showing signs of battle fatigue. Still searching for prey, Semmes sailed down to Cape Town, South Africa, where to his surprise and relief he and his crew were fêted as heroes. Nothing so exciting or glamorous had visited Cape Town for a very long time, and the residents of this lonely outpost of the British Empire could hardly believe their good fortune. They were so welcoming—inviting the Southerners on big game and ostrich hunts—that twenty-one sailors deserted, leaving Semmes with a serious shortage of men. After much scraping around, his executive officer, 1st Lieutenant John McIntosh Kell, was able to find only eleven replacements. Fortunately, two Prussian naval officers who had been shipwrecked near Cape Town also joined as master’s mates.

8

The appearance of the gunboat USS

Vanderbilt

off the Cape put an end to the

Alabama

crew’s two-month respite from their harsh life at sea. At midnight on September 24, the ship set sail during a heavy gale for the fertile hunting grounds of the Far East, where Semmes knew he was not expected.

27.1

An article entitled “Our Cruise” in the

Southern African Mail

by George Townley Fullam, one of the English officers on board the

Alabama,

eventually reached England in the autumn. Fullam described the ship’s adventures, from her narrow escape from Liverpool harbor in July 1862 to her glorious entry into Cape Town twelve months later. Embarrassingly for the British government, Fullam claimed that someone in Her Majesty’s Customs had alerted the Confederates to the

Alabama

’s pending seizure, allowing her to get away in time. Not surprisingly, the U.S. legation was incensed by this revelation. Charles Francis Adams ordered the article to be printed as a pamphlet and for a copy to be sent to Lord Russell with a strongly worded complaint attached.

Although Russell insisted to Adams that the British government could not be held responsible for the depredations of the

Alabama,

privately he was worried that the United States might carry out its threat—first made by Seward and Adams in 1862—to sue Britain for damages after the war.

10

Russell discussed with the law officers whether they should bar the raider from all British ports around the world, but in their opinion such a move could be interpreted as an admission of guilt regarding the

Alabama

’s escape. Russell was relieved when an alleged violation of British neutrality at Queenstown, Ireland—involving USS

Kearsarge

and sixteen Irish stowaways—for once reversed the direction of complaints, giving him the opportunity to play the injured party with the U.S. legation.

27.2

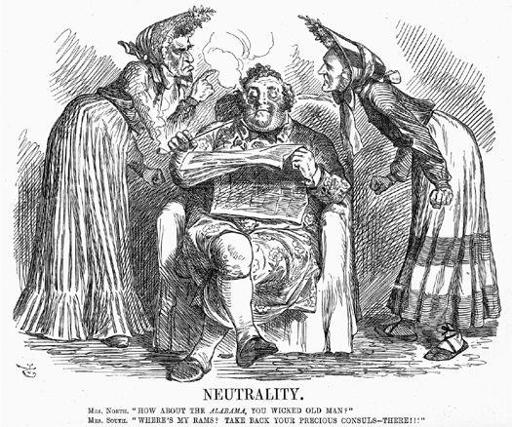

Ill.49

The Union and the Confederacy both rail at a determinedly calm John Bull, Punch, November 1863.

The British government was fully aware that large numbers of Irishmen were enlisting in the Federal army; Consul Archibald had observed the crowds at Castle Garden, the immigration depot on the southernmost tip of Manhattan, and estimated that every week, 150 Irish laborers were stepping off the boat and into the arms of recruiters.

11

A Home Office clerk compiling passenger statistics first spotted the phenomenon in April 1863, when he noticed a sharp increase—it had almost tripled since 1862—in the number of single male travelers. After carefully reviewing all the statistics from the past three years, the Home Office discovered that the actual increase in the emigration of unmarried Irishmen was roughly ten thousand a year (a figure the government decided it could accept without too much heartache).

12

The Confederate government was also concerned about the vast influx of Irish immigrants to the North, and in August 1863 sent its propagandist in France, Edwin De Leon, to Ireland, where he diligently spent several weeks publishing articles about the horrors of the war. James Mason followed in September, but his findings confirmed their worst fears. The Irish were so poor after two failed harvests, Mason wrote to the Confederate secretary of state, Judah P. Benjamin, on September 4, 1863, “that the temptation of a little ready money and promise of good wages would lead them to go anywhere.”

13

But the draft riots in New York in mid-July had given Benjamin hope that it was not too late to stem the tide. The accusation that the U.S. government was throwing its Irish immigrants into the slaughtering pen was gaining credibility following the near obliteration of the Irish Brigade at Fredericksburg and Gettysburg. Benjamin dispatched to Ireland two more agents, Lieutenant James Capston, a former Dubliner, and Father John Bannon of Vicksburg, with orders to discourage Irish immigration using all means at their disposal.

The exposure of the stowaways on the

Kearsarge

had been Lieutenant Capston’s first success. But he could not uncover any proof for the Home Office that Captain Winslow had acted deliberately, nor did he find evidence of official Federal recruiting in Ireland. (The U.S. government had no need to send over agents when there were plenty of unscrupulous entrepreneurs ready to assume the risk themselves in return for a large cut of the bounty paid for volunteers.) Capston and Bannon soon gave up that particular line of attack and concentrated instead on spreading anti-Northern propaganda. The two Confederate agents tried to tap into Irish nationalist sentiment by comparing the South’s fight for independence with Ireland’s. They distributed thousands of handbills warning potential emigrants that they would end up as cannon fodder if they went to the North. Father Bannon used his church connections to ensure that the injustices endured by the Irish community in the North were broadcast from the pulpit. Although emigration continued apace, the agents successfully rubbed off any glamour in volunteering for the North.

—

The danger of having their arms shipments seized by the U.S. Navy and their commerce raiders impounded by the government had driven the Confederates’ activities in Britain underground. “The cheapest and most favorable market, that of England, was well nigh closed to the Confederacy, while the United States were permitted to buy and ship what they liked, without hindrance, and at the ordinary current prices,” complained James Bulloch in his memoirs.

14

Matthew Fontaine Maury had hoped to launch a second Confederate cruiser, CSS

Rappahannock,

but he was forced to send the vessel from Sheerness, Kent, on November 24, 1863, with its hull and boilers still needing work simply to prevent its seizure by the authorities. The cruiser just managed to reach Calais, where it had remained since December, awaiting repairs.

The blockade was also drastically inhibiting the South’s communications. Rose Greenhow had been in Paris since December, trying to arrange an interview with Emperor Napoleon III: “I would write you many interesting particulars,” she wrote to a friend in Virginia, “but the publication of the late intercepted letters is a good warning to me to be careful. If you will get from Mr. Benjamin a cipher and use my name as the key, I can then tell you many things.”

15

The “intercepted letters” were those from CSS

Robert E. Lee,

which had been caught on November 9, 1863, on its twenty-first trip between Wilmington and Nassau. The U.S. Navy also captured the Confederate Ordnance Department’s two remaining supply ships the same night, but the real prize was the

Lee.

On board were two lieutenants from the Royal Artillery, the Belgian consul, and a mailbag containing dispatches from James Mason for the Richmond cabinet.

16

The mailbag also included the private correspondence of his colleague Edwin De Leon, which revealed every aspect of his propaganda campaign—from his attempts to bribe French journalists to his methods of spreading disinformation. But by the time De Leon’s letters appeared in the New York and London press, the disgraced agent was already on his way back to the South, having been dismissed by Jefferson Davis not for the exposure, but for criticizing Judah Benjamin, who had taken the side of John Slidell in the acrimonious relations between the two agents.

Slidell had refused to work with De Leon after he learned that the propaganda agent had opened and read Confederate dispatches intended for him alone. Convinced that De Leon was after his position, Slidell tried to undermine him at every opportunity. He was equally hostile toward Rose Greenhow and discouraged his wife from helping her find a school for her daughter. (Eventually Rose accomplished the task on her own, placing little Rose in the Convent du Sacré Coeur, a Catholic boarding school with many foreigners among its two hundred girls.)

17

Slidell’s suspicions about De Leon were groundless, but he was right to be fearful of interference from Rose: “I have come to the conclusion that we have nothing to hope from this side of the Channel,” she wrote to President Davis on January 2, 1864.

18

The French mission was a waste of time and resources, she concluded: Slidell cared more about his social life than Confederate diplomacy, and Mason’s grasp of French was too poor for him to be effective in Europe. She advised Davis to recall Slidell and send Mason back to London before the work of two years withered on the vine.

Rose thought Louis-Napoleon’s sympathy was entirely mercenary: “They want tobacco now quite as much as the English want cotton … and I believe that if we were to stop the going out of either cotton or tobacco, it would have more effect than anything else.”

19

Having failed to reach the emperor through friends or contacts, she audaciously wrote to him on January 11 requesting a meeting, and much to Slidell’s annoyance, she was granted an interview at the Tuileries on the twenty-second. The little drama was observed by the Maryland journalist W. W. Glenn, who, having spirited Lawley, Vizetelly, and a host of other British visitors across Southern lines, was now in Paris visiting a friend. Glenn’s own feelings about Rose were ambivalent—he had seen her once before in Mason’s company and thought her “a handsome woman, rouged and elaborately gotten up”—but he was still amused by Slidell’s consternation over her success with the emperor: