A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (73 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

17.1

Vallandigham reveled in being called a “Copperhead,” a term used by the Republicans to imply that the Peace Democrats were like snakes, ready to strike on behalf of the South without warning—and by the Democrats themselves to symbolize their commitment to freedom and states’ rights, since copper pennies bore the word “liberty.”

17.2

Dr. Mayo was shocked when he visited Congress. “In both houses,” he wrote, “the occupation of members seemed to consist of calling each other traitors.” He was a witness to some of the least edifying scenes in Senate history. On January 27, 1863, Senator Willard Saulsbury of Delaware made his infamous harangue from the Senate floor. He was, recorded the doctor, “in a state of hopeless drunkenness, and insisted on making a speech, and when rebuked by the chairman and threatened with removal by the sergeant-at-arms, drew and cocked his revolver, and threatened to shoot any body who interfered with him.” The standoff continued for some time, until Saulsbury was persuaded to leave.

17.3

It was General Butler who invented the term “contraband.” He was the commandant of Fortress Monroe in 1861 when three runaway slaves arrived asking for sanctuary. When their former Southern masters requested their return, Butler refused, arguing that slaves were “contraband of war,” since the South was using them as “tools” to sustain the war effort. The term stuck.

17.4

These included former employees from the Irish estate of William Gregory, the leading Confederate sympathizer in Parliament. Gregory’s gamekeeper, Michael Conolly, had followed his family to America and volunteered for the North. His action cost him his arm at Fredericksburg. Several of Conolly’s cousins were also wounded, but his two brothers had come out of the battle unscathed. “As for my part,” Conolly wrote to Gregory from his hospital bed, “I will not be able to join the company again.”

17.5

Wynne had escaped by “breaking out a panel in his door.” He was one of only four escapees in the prison’s history. Wynne always insisted that he acted on his own, and the legation’s records are silent on the matter.

17.6

Hartington’s faux pas took on a life of its own. The lapel badge story was repeated ad nauseam as incontrovertible proof of the English aristocracy’s hatred of the United States. The American poet and literary critic James Russell Lowell included the incident in his diatribe against European arrogance in his essay “On a Certain Condescension in Foreigners” (1869), changing the story slightly in order to have Lincoln meet Hartington after the ball and deliberately insult him for having shown disrespect toward the North.

EIGHTEEN

Faltering Steps of a Counterrevolution

Attack on Charleston—British public opinion begins to change—The illustrious Maury, Pathfinder of the Seas—Espionage—Lord Russell is thwarted by John Bright—Wilkes again

T

he “Yankee Armada” set sail for Charleston at the beginning of April 1863. Frank Vizetelly was still in the city and could hardly wait for the clash to take place. His reports for the

Illustrated London News

became increasingly one-sided as he watched the city prepare for the attack. “I have every faith in the result of the coming encounter,” he wrote, “for never at any time have the Confederates been more determined to do or die than they express themselves now.”

1

More important than the Confederates’ determination, however, was the lack of preparedness of the U.S. invasion force. Dr. Mayo inspected the fleet of seven monitors

18.1

and two ironclads before it left the Washington Navy Yard “and sincerely pitied those who had to go to sea in it.” The decks of the monitors were barely a foot above water. He thought the slightest turbulence would probably swamp the vessels and send them to the bottom of the sea.

2

Admiral Samuel F. Du Pont was similarly pessimistic about his fleet, but the public clamor to capture and punish Charleston for starting the war was gathering force. Lincoln interpreted Du Pont’s reluctance as McClellan-like timidity. “Doom hangs over wicked Charleston,” boomed the

New York Herald Tribune

on the eve of the fleet’s departure. “If there is any city deserving of holocaustic infamy, it is Charleston.”

3

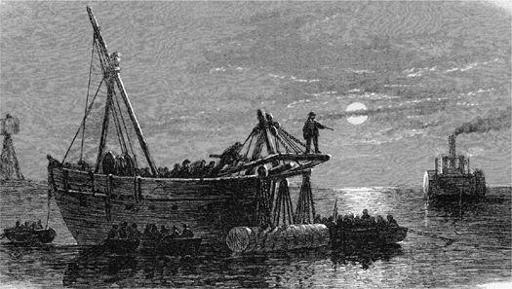

Ill.33

Confederates deploying torpedoes by moonlight in the harbor channel, Charleston, May 1863, by Frank Vizetelly.

Du Pont’s fleet sailed into the harbor on April 7. At 3:00

P.M.

urgent peals rang across the city, alerting the inhabitants to take cover. Confident in Beauregard’s defenses, many chose to watch from rooftops and balconies rather than hide in their houses. Frank Vizetelly ran from the Charles Hotel down to the Battery Promenade, where he jostled with the spectators for an unobstructed view of Fort Sumter. “I sketched the scene,” he wrote for the

Illustrated London News,

“and finished the drawing in the evening, while the garrison of Fort Sumter were repairing the damages.” Admiral Du Pont’s gloomy prediction that his fleet would be overwhelmed was soon fulfilled. The fight lasted a mere two and a half hours. But in that time his fleet was crippled and his best ironclad steamer, the

Keokuk,

was sunk.

“I don’t think the Yankees can capture Charleston, do what they will,” Henry Feilden wrote after the battle. “In six weeks more the unhealthy season will come on, and the scoundrels will die on this coast like rotten sheep.” It was his firm belief that the South would win its independence by Christmas. In the meantime, he planned to convert his entire savings into Confederate currency while it was still cheap to buy. Vizetelly was similarly ebullient about the South’s prospects of victory. “The fight may be renewed at any moment if the Federals have the stomach for the attempt,” he informed his readers back home, “but I think they have suffered too much.”

4

The U.S. secretary of the navy, Gideon Welles, was furious with Du Pont for failing to put on a better show. Embarrassed by yet another naval defeat, he wondered whether it was even worth making a further attempt: “Nothing has been done, and it is the recommendation of all, from the Admiral down, that no effort be made to do anything,” Welles wrote gloomily in his diary. “I am by no means confident that we are acting wisely in expending so much strength and effort on Charleston, a place of no strategic importance. But it is lamentable to witness the … want of zeal among so many of the best officers of the service.”

5

Vizetelly’s triumphant reporting of the Union’s repulse contributed to the sour mood in Washington. The secretary of war, Edwin Stanton, was an avid reader of the English press, particularly those journals that were sympathetic to the South. Stanton would shut his office door, settle down on the sofa, and spend the afternoon discovering from Britain’s finest journalists why the North deserved no pity and why he, especially, was the worst sort of bungler. According to one of his clerks, it was almost a form of relaxation for him.

6

—

Contrary to Stanton’s belief that all of England sympathized with the South, support for the North was growing. The London consul, Freeman H. Morse, whose duties had expanded to include propaganda and public agitation, told Seward that there had been a “revolution” since Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

7

Despite the initial skepticism toward the Proclamation and the best efforts of

The Times

to portray it as a cynical ploy to encourage race riots—or at the very least force Southern soldiers to return to their homes to protect their families—the message that the war had a moral purpose seemed to be reaching the British public.

Among the initial signs was a rise in pamphlets and books putting forward the case for the North. James Spence’s seemingly unassailable arguments in

The American Union

for recognition of the South were picked apart to devastating effect by the economist John Elliot Cairnes in his book

The Slave Power,

which appeared in the autumn of 1862 and went through several editions after the Emancipation Proclamation. Cairnes was followed by the actress Fanny Kemble, who published her diary,

Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838 – 1839,

written during her exile on her former husband’s slave plantation in Georgia, and William Howard Russell, whose account of his stay in America, entitled

My Diary North and South,

verified many of her observations.

8

The

Spectator

journalist Edward Dicey also wrote a travelogue

—Six Months in the Federal States

—that tried to correct many of the distortions and caricatures of Northern culture that pro-Southern journalists had propagated. An increase in the number of volunteers calling at the legation reflected the changing perception of the war. “Applications for service in our army strangely fluctuate,” wrote Benjamin Moran in his diary on January 14, 1863. “For some time past they have been but few. Since the announcement of the President’s determination to adhere to his emancipation policy they have again become numerous and today we have had a French and British officer seeking employment.”

9

Moran was surprised by the wide range of motives and financial circumstances of these would-be volunteers; as far as he could tell, some were genuine idealists, but others were simply looking for an escape from their daily existence. Another surprise was waiting for him when he went to church. The vicar had never mentioned the war before, but on this Sunday he announced during prayers, “Our hearts in this great contest are with the North,” which was answered with a deep “Amen” from the congregation.

10

“Emancipation Meetings continue to be held in London every week, sometimes four or five a week at some of which two and three thousand people have been present and in a majority of cases unanimously with the North. Other portions of the country are following the example of this city and holding meetings with about the same result,” Consul Morse reported to Seward.

11

James Spence spoke passionately at an antislavery meeting in Liverpool, but to his surprise he failed to convince a mixed audience of merchants and tradespeople that the South would also abolish slavery as soon as it won independence.

12

The public was far more interested in hearing from President Lincoln than from Spence. Encouraged by Charles Sumner, Lincoln had written an eloquent letter to the “Workingmen of Manchester” thanking the cotton workers for their patience and sacrifice. “Whatever misfortune may befall your country or my own,” declared the president, “the peace and friendship which now exist between the two nations will be … perpetual.”

13

Morse was being helped by Peter Sinclair, a formidable and energetic Scotsman who had spent the past six years building a Canadian-American temperance organization called Bands of Hope. Sinclair had lately returned to England with the specific intention of giving his aid to the North. “Mr. Sinclair has been laying facts, figures and arguments before a committee of the old Emancipation Society, one of the most influential organizations in England,” Morse informed Seward in January. Even though some veteran campaigners like Bishop Samuel Wilberforce and Lord Shaftesbury remained unconvinced (much to Henry Hotze’s glee), Sinclair had been remarkably successful in convincing a wide range of individuals—including “merchants, bankers, lawyers, literary men, etc.”—that abolition was possible only in a united America. The hitherto pacifist British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society changed its stance and became actively involved in the counterpropaganda war, secretly supplying Moran with information about Confederate activities in the financial markets.

14

Sinclair was also the leading organizer of the Emancipation Society’s massive demonstration at Exeter Hall on January 29. Henry Adams managed to secure a seat at the meeting and was thoroughly uplifted by the experience. The politicians, Henry told his brother afterward, were going to have to listen to their constituents or risk being “thrown over.”

18.2