A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (91 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

The British consul was able to rescue Ann Anderson, a Barbadian ship’s cook, who was being chased down West Street by a mob. Fortunately, she had time to hammer on the doors of the consulate at No. 10 and be pulled to safety. Twenty blocks north of Fremantle’s hotel, at Forty-third and Fifth, stood the Colored Orphan Asylum, home to 237 Negro children aged twelve and under. Three thousand rioters gathered at the front, forcing the asylum superintendent hurriedly to evacuate the small occupants through the back. One little girl was left behind. She was found cowering under her bed by the rioters and beaten to death.

29

Farther downtown, another mob, heavily armed and ten thousand strong, appeared in front of the police headquarters on Mulberry Street and were confronted by two hundred club-wielding policemen. After twenty minutes of hand-to-hand fighting, the mob turned tail.

30

The violence was sporadic but clearly the result of direction. Small working parties cut down the telegraph poles along Third Avenue, isolating each of the twenty-six police precincts from central command. Others stopped railroad cars and pulled up the tracks. Rioters broke into the Armory at Twenty-first Street and Second Avenue, helping themselves to the rifles and carbines within. A separate mob headed over to Newspaper Row, across from City Hall Park, where the

Tribune

and

The New York Times

had their offices. The

Times

editor, Henry Raymond, kept the crowd at bay with three borrowed Gatling guns, but the

Tribune

building had only a small band of policemen guarding its entrance.

31

Rioters burst through the doors to find that the staff had used bales of newspaper to barricade the stairs. Unable to push their way through, the mob set fire to the counters and went off in search of other prey.

By sunset, the orange sky was streaked with columns of black smoke. Hiding inside the St. Nicholas Hotel, the mayor of New York, George Opdyke, and the U.S. Army general in command of the Department of the East, John Ellis Wool, passed their responsibilities back and forth as a group of prominent citizens implored them to declare martial law. At 9:30

P.M.

the New York head of the telegraph service, Edwin Sanford, sent a wire to Washington from Jersey City, whose station was still operating: “In brief the city of New York is tonight at the mercy of a mob whether organized or improvised, I am unable to say.… The situation is not improved since dark. The program is diversified by small mobs chasing isolated Negroes as hounds would chase a fox.”

Fires burned uncontrollably all over the city. Establishments that employed blacks as well as whites, such as bars and brothels, were particularly targeted. Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell feared for her infirmary and ordered the servants to close the shutters and lock the doors. Every light was extinguished, leaving the occupants sitting in darkness as the muffled but unmistakable shouts of a lynch mob torturing its victim could be heard through the walls. Some of the white patients became hysterical, begging Dr. Blackwell to save the hospital by expelling the black occupants. She had almost succeeded in calming them down when one of the contraband patients went into labor. Terrified that the woman’s cries might be heard from outside, Elizabeth and two nurses carried her to the back of the infirmary. There, in a dimly lit room, they worked all night to deliver the baby.

Meanwhile, mobs were prowling the waterfront, attacking British vessels known to have black crew members. One black sailor was lynched and another suffered life-threatening injuries. Archibald turned the consulate into a safe house, but with limited space at his disposal he had to ask the legation in Washington for help. Although there were no carriages or omnibuses running, an intrepid secretary managed to reach Jersey City to send a ciphered telegram to Lord Lyons: “I consider a man-of-war essential here immediately to receive and protect British Black crews.” Lyons replied that HMS

Challenger

was on its way, but the warship would not reach New York for at least another twenty-four hours. Archibald could not wait that long. In desperation, he contacted the French consulate, which arranged for Admiral Reynaud to offer the

Guerriere

to British blacks. The French frigate steamed into the harbor, opened the gun ports, and let down rope ladders. The captain shouted through his megaphone that all colored Britons were to board the vessel by order of Consul Archibald. Seventy-one black British sailors clambered aboard, and a further seven British vessels moored alongside her.

The violence on Tuesday included mass looting as well as more raids on the armories. Rioters sacked Brooks Brothers, burned the 26th Precinct house, destroyed the Harlem River Bridge, demolished the Washington Hotel, and attacked the mayor’s house. Fifty to sixty thousand people were said to be out on the streets; barricades were being erected at various points in the city to hinder the movement of police. “Immediate action is necessary, or the Government and country will be disgraced,” Edwin Sanford telegraphed the War Department. The governor of New York, Horatio Seymour, declared a state of insurrection and also asked Washington for troops. A politician to his fingertips, he assured the angry crowd outside City Hall that he was their friend and supporter against the draft, but his appeal failed to stop the violence. Finally, late on Tuesday night, Washington ordered five regiments to the city.

“Wednesday begins with heavy showers, and now, (ten

A.M

.) cloudy, hot, and steaming,” wrote the treasurer of the Sanitary Commission, George Templeton Strong, in his diary; “there will be much trouble today.”

32

When Fremantle went down for breakfast he found soldiers guarding the hotel (Robert Lincoln, the president’s eldest son, was coming home from Harvard and happened to be one of the guests). But outside, the immediate streets were deserted; the entire city appeared to be in the middle of a mass exodus. There were no carriages, and he had to walk down to the waterfront. “I was not at all sorry to find myself on board the

China,

” wrote Fremantle, his final memory of the city “a stone barricade in the distance, and [the sound of] firing going on.”

33

The mob and the military had evidently found each other.

34

At midmorning a small funeral cortège started out from West Fifty-third Street. Dr. Charles Culverwell’s wife, Emma, could no longer wait for the rioting to subside. Their three-year-old daughter had died the previous Sunday of infant cholera. Emma did not know where Charles was, although he had promised to come to them. Terrified for herself and her surviving daughter, she attempted to slink unnoticed past the rioters. They barred her way, forcing Emma to plead for permission to bury her child.

35

All this time Culverwell had been begging his hospital superiors in St. Louis to grant him compassionate leave. In desperation he annulled his contract on July 16, donned civilian clothes, and headed for New York.

By Wednesday night, HMS

Challenger

had still not appeared; however, a U.S. warship had joined the

Guerriere,

training its guns on Wall Street to deter an attack on the financial district. On Thursday, rioters discovered they were fighting not just a few brave souls but ten thousand veterans of Gettysburg. During the night there was a final, bloody convulsion at Gramercy Square on Twentieth Street that left one soldier and fifteen rioters dead. But at noon on Friday, the roars and explosions ceased as suddenly as they had begun; Elizabeth Blackwell unlocked the doors of the infirmary for the first time in forty-eight hours. Edwin Sanford telegraphed Washington at 3:45

P.M.

that the “city continues very quiet.” George Templeton Strong blessed the change in weather: “Rain will keep the rabble quiet tonight.”

36

Early estimates put the death toll at anywhere from a hundred to a thousand people, but the physical devastation was obvious. Whole blocks had been burned and more than three hundred buildings destroyed.

37

Among the homes that had been ransacked was Colonel Nugent’s—a punishment for his role in enforcing the draft.

“It is a fact that the rioters have been almost entirely Irish,” Archibald wrote to Lord Russell, and their fury toward “the poor Negro people” had not abated simply because of the presence of troops.

38

HMS

Challenger

arrived on Saturday and accepted transfer of the refugees from the

Guerriere.

The seventy-one colored seamen remained sequestered below for several days. “There are, however, many lawless characters still about the wharves,” Archibald wrote on July 20, “and the masters assure me that it is not safe for the Negro sailors to return to their own vessels.”

39

Although the consul was due to take his annual leave, he remained in the smoldering city until he was confident that the danger had passed.

—

Lyons had not heard from Seward during the crisis; violence had flared in other parts of New York, and the secretary’s own house in Auburn was attacked. The incident was relatively minor—a rock hurled through a downstairs window—but for several nights Frances Seward had stayed awake, waiting for the sound of breaking glass. Be prepared for the loss of our home, Seward wrote stoically to his wife; if the war brings an end to slavery, “the sacrifice will be a small one.”

40

Despite Archibald’s brave conduct during the riots, British subjects “are far from being pleased either with HM Government or with HM Minister here,” Lord Lyons told Lord Russell on July 24. No one thought that the legation was doing enough to protect Britons from the rampant cheating and illegal conscriptions that accompanied the latest draft effort. The legation staff was working late into the night trying to keep abreast of the rapidly increasing number of case files. Few cases, if any, were straightforward.

41

Young Frederick Farr refused to be helped; he ignored the attachés’ inquiries and would not respond to letters from his father’s friends. “That is a queer boy of yours,” one of them wrote to Dr. Farr in exasperation. “I have not been able to draw a line from him.” Farr’s commanding officer reported that the boy was “in excellent health and spirits” after Gettysburg and only wanted to be left alone.

42

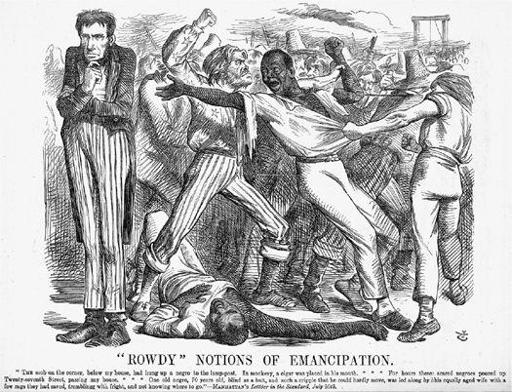

Ill.44

Punch accuses President Lincoln of doing nothing to save free blacks from the rioting Irish.

Lyons knew there was nothing to be gained from telling British subjects that they should count themselves fortunate to be in the North and not in the South, where the situation was far worse. In addition to being tricked or beaten into joining regular regiments, Britons were being rounded up to man “home defence militias,” and there was nothing the consuls could do about it; Judah P. Benjamin expelled Consul George Moore from Richmond in June for allegedly exceeding the limits of his purview. One of the very few British conscripts to escape to the North, a Mr. R. R. Belshaw, thanked Lyons “for the interest which you have taken in my case,” but, he complained, “thousands of British subjects are daily suffering in the Confederate army as I have done and yet there is no relief; though England speaks she says nothing.”

43

Lyons did not have a satisfactory answer for Belshaw; the diplomatic situation in the South was beyond his control and yet somehow still perceived by Washington and London as his responsibility.

23.3

Lord Russell pondered whether they ought to send a military agent or commissioner to Richmond, taking the same route as Fremantle in order to avoid running the blockade, but Lyons persuaded him against the idea. The North would object, and the Confederate government would no doubt ignore the agent as it did the consuls. Seward was adamant that any British attempt to contact the Southern authorities would be regarded by the United States as an act of deliberate provocation, if not war.

Lyons did not understand what drove the secretary of state. Sometimes they seemed to be in the most perfect harmony. Tucked away in the Seward archives are private letters showing that Lyons often coached Seward on how to frame his official responses to British complaints.

45

But Seward was always playing more than one game at a time. In early August he asked Lyons if Britain would be prepared to join the North in fighting the French takeover of Mexico. “It would no doubt be a relief to Mr. Seward,” Lyons reported after the interview, if Britain assumed the burden of defending the Mexicans—and the Monroe Doctrine—against the emperor’s imperialist designs. But “England would run the greatest risk of being ultimately sacrificed without scruple by the United States.”

46