A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (95 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Bulloch was surprised that the government had seized the rams without first obtaining legal sanction or charges against Lairds. After a month went by without any sign of legal action, he began to wonder if the process was being deliberately drawn out in order to give the law officers more time to prepare their case. On October 28 “Historicus” attacked the rams in

The Times

(this was William Vernon Harcourt’s return to print after the death of his wife in April), condemning the Confederates’ illegal use of British shipyards and arguing for a determined response from the government. Bulloch realized that “Historicus” was preparing public opinion for the government’s clampdown on Confederate operations in England; whether or not the rams case went to court, the ships would never be allowed to leave. The following day brought more disappointing news. CSS

Georgia

had dropped anchor at Cherbourg in so dilapidated a state as to be on the verge of sinking.

The raider had destroyed nine ships during her six-month adventure. But according to Lieutenant James Morgan, the final weeks had resembled a gothic horror story, full of madness and savagery. Captain Maury had suffered a nervous breakdown near the Cape of Good Hope, and the enforcement of discipline had fallen to the charming but weak Lieutenant Evans. There were constant fights and several attempted mutinies: “things had gone from bad to worse than bad until one day some of the stokers discovered that a coal bunker was [all that] separated [them] from the spirit-room,” wrote Morgan;

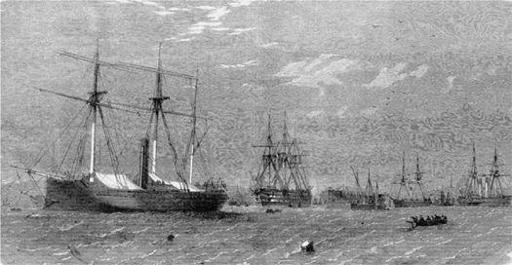

Ill.46

The Royal Navy keeping watch over the Lairds’ rams in the Mersey.

and inserting a piece of lead pipe into the hole they got all the liquor they (temporarily) wanted. This they distributed among the crew and soon there was a battle royal going on the berth deck which the master-at-arms was unable to stop.… Here was a pretty kettle of fish! … I suddenly leaped upon the man and bore him to the deck, where, in a jiffy, the master-at-arms placed the bracelets on his wrists. The other mutineers, quietly extending their arms in sign of submission, were placed in irons, and confined below. The discipline of the ship needed as much repairing as the vessel did herself. It was time the

Georgia

sought a civilized port for more reasons than one.

33

Clerks at Fraser, Trenholm had carefully stored the crew’s letters, to be distributed on their eventual return to port, and receiving news from home helped calm the febrile atmosphere on the ship. “There was great rejoicing for all save me,” recorded Morgan after the letters were delivered at Cherbourg. He had received two: the first told of the death of his brother George, a captain serving in the 1st Louisiana Infantry in Virginia; the second, that Gibbes, his other brother and a captain in the 7th Louisiana, had died a prisoner of war on Johnson’s Island in Lake Erie. Morgan’s adventures at sea suddenly seemed trivial to him after the terrible news from home. From this moment, his one ambition was to return to the South and fight the Federals.

—

In the Southwest, the capture of Vicksburg and Port Hudson had brought a temporary quiet to the Mississippi region. General Banks’s XIX Corps returned to camp, and the 133rd New York Volunteers, Colonel Currie’s regiment, resumed its garrison duty in Baton Rouge. Currie had recovered from his wounds, and much as he retained a fondness for his men, he loathed inaction more and had applied for a transfer. “I have at least one strong arm left,” he wrote to Thurlow Weed, “and I am only desirous that any merit I may possess … may meet with equal favor with my compeers.”

34

Currie’s eagerness to be in the thick of danger was rare: most of the injured and sick wanted to be as far away from the fighting as possible.

Ebenezer Wells and Dr. Charles Mayo were both sent north, Wells to a hospital in Kentucky and Mayo to Saratoga Springs in New York to recover from typhus. His last weeks in Vicksburg had been a blur to him, but the illness saved his life in an unexpected way. On August 18, Mayo had become so unwell that a friend insisted he spend the night in town with him rather than on his ship, the

City of Madison.

During the night there was an explosion on the

Madison

that claimed the lives of all those on board. After this near brush with death, the authorities finally took pity on Mayo and shipped him out of Vicksburg. The War Department accepted his resignation from the army on September 8, although it was another two weeks before he was well enough to sail for England on the twenty-second, never to return to America.

24.3

Mayo’s quiet departure contrasted with the noisy and sometimes violent integration of the thousands of new army recruits produced by the draft, many of whom were determined to desert at the first opportunity. Even the volunteers were often cynical about their situation. “As I fully intend to desert if I don’t get good treatment, I enlisted under the name of Andrew Ross,” James Horrocks wrote to his parents on September 5, 1863. The nineteen-year-old had run away from Lancashire to escape the financial burden and shame of having fathered an illegitimate child.

35

Volunteering in the Federal army seemed like an excellent prospect to the prodigal son: “I shall get when mustered in $200 from the state of New Jersey, 50 dollars from Hudson City (where I enlisted) and 25 dollars from the Government. This, together with a month’s pay in advance, will make $288 cash down,” he told his parents. “I shall be able to save more money as a soldier than as a clerk with 400 dollars a year (that is a pretty good salary in New York).”

36

Horrocks was surprised by the large number of foreigners who had enlisted with him. “The Company I am in is a motley assembly—Irish, Germans, French, English, Yankees—Tall, Slim, Short, and Stout. Some are decently behaved and others uncouth as the very devil,” he wrote home. One-fifth of the regiment was English, including all the sergeants. Nevertheless, he was pretending to be a Scot in order to avoid the anti-English prejudice among the Americans.

37

The desertions began as soon as the men received their bounty money; but far from deserting himself, Horrocks was sent out with several others to find the absconders and returned with more than a dozen. The ecstatic spirit of patriotism and duty that had animated the first wave of volunteering in 1861 had died out; Horrocks’s desire “to keep myself pretty secure and safe” reflected the feelings of a large majority of the new soldiers, especially among the conscripts.

In the South, where there were neither untapped reserves of young men nor legions of foreigners arriving each week, part-time raiders and guerrilla outfits were playing an increasingly important role in the war effort. Northern Virginia, where Charles Francis Adams, Jr., was stationed, was Mosby country. The eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay, two hundred miles to the south, had become John Yates Beall country.

As with Mosby, the war had enabled the twenty-eight-year-old Beall to redefine himself. His father’s death when Beall was twenty had forced him to sacrifice a promising legal career in order to care for his widowed mother and five younger siblings. Service in the Confederate army had provided an honorable escape route from domestic responsibilities, until a bullet to his right lung seemed to cut short his military career.

Beall moved to Canada in 1862, where he tried to establish a business selling game, until a friend told him about the Confederate navy operations in England. It sounded so exciting that he wanted to “join them and take of their fortune for good and evil.”

38

In the time it took Beall to reach Richmond in February 1863, he had changed his mind about going to England, however, and instead saw himself as a waterborne version of John Mosby. The Confederate navy secretary, Stephen Mallory, was skeptical of the idea. He appointed Beall acting master on March 5—the usual commission for gentleman volunteers—but gave him no other help or encouragement: Beall would have to supply his own boat, uniform, weapons, and volunteers, none of whom could be eligible for conscription. Furthermore, although they would be able to keep whatever booty they captured, they would not be paid.

Beall set about recruiting from the groups still open to him—the middle-aged, stranded foreigners, and wounded veterans like himself. By September 1863, his Confederate Volunteer Coast Guard, or “Beall’s Party,” as it was known, had grown to eighteen and included two newspaper editors and their apprentices, a couple of sailors, and two Scotsmen: Bennet Graham Burley and John Maxwell. Burley had recently been imprisoned in Castle Thunder, the converted warehouse in Richmond that housed spies and political prisoners. The twenty-three-year-old Glaswegian had arrived in the South the previous year, bearing designs for a powerful underwater limpet mine, which in theory could penetrate armor plating. (The explosive device had been invented by his father, Robert Burley, Jr., the owner of a toolmaking factory, who, unable to secure commercial interest in his invention at home, had given the plans to his son to take to America.)

Bennet Burley had chosen the South on the assumption he would have a better chance of being noticed. His hunch was correct, though for all the wrong reasons. Fortunately, the new chief of the Confederate navy’s Bureau of Ordnance and Hydrography, John M. Brooke, was also an inventor. As soon as Brooke saw Burley’s plans, he knew that the youth was no spy and arranged for his release. Having regained his freedom, Burley displayed the daring and initiative that later made him one of the most famous war correspondents of his generation and persuaded Brooke to let him test the mine on a Federal ship. John Maxwell was assigned to help Burley carry out his mission, but Burley’s father had missed something in the design and at the final moment they were unable to ignite the fuse.

The mine’s failure to explode merely whetted Burley’s and Maxwell’s appetite for danger, and they officially joined Beall’s Party on August 13, 1863, the day their navy commissions as acting master came through. Having acquired two small boats, the black

Raven

and the white

Swan,

the raiders went on to harass Federal shipping around Cape Charles and Fortress Monroe so successfully that a joint U.S. military and naval expedition was ordered to find them.

39

Beall’s dream of emulating Mosby had come true.

John Mosby himself had received a bullet wound in August and had only recently returned to active duty. He decided to prove his recovery by reprising his spectacular raid against Sir Percy Wyndham in March. This time the target was Francis Pierpont, the governor of pro-Union West Virginia, who was staying in temporary quarters in Alexandria. The raid was unsuccessful, but it reminded Wyndham, whose recovery from his leg wound had been reported with great excitement by local newspapers, that the contest between them was still alive.

40

Wyndham’s New Jersey Cavaliers were camped at Bristoe Station, right in the center of Mosby country, but Wyndham was unable to indulge his fantasies of revenge, having again been moved up to brigade command. Union general George Meade had ordered his cavalry corps to find out where Lee was moving with the Army of Northern Virginia. Despite almost constant skirmishing with Jeb Stuart’s troops, the cavalrymen were able to report that Lee had dispatched General Longstreet and the First Corps to an unknown destination. “I should be glad to have your views as to what had better be done, if anything,” Meade asked General Halleck on September 14. Lincoln wondered what Meade was waiting for: “He should move upon Lee at once,” the president wrote impatiently to Halleck.

41

Meade did indeed move, but slowly and deliberately, to the relief of the Confederates. President Davis and General Lee had decided that there was no alternative to sending Longstreet to Tennessee, which was in danger of being captured by Union general William Rosecrans and his Army of the Cumberland. If Rosecrans succeeded, yet more vital railroads would be lost, railroads that were Virginia’s only lifeline to the much reduced Confederacy. Tennessee lay across the top of the South like an elongated anvil, touching the borders of Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia; the Confederates feared that its conquest would allow the North to carve up the South like a joint of beef. The implications of such a disaster added to the Richmond cabinet’s anguish after the summer of defeats. The chief of ordnance, Josiah Gorgas, mourned in his diary: “Yesterday we rode on the pinnacle of success—today absolute ruin seems to be our portion. The Confederacy totters to its destruction.”

42