Alex's Wake (43 page)

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

We also stop at the Shoah Museum to see its Wall of Names, erected in tribute to the Jews who were sent to the East, a wall that includes the engraved names of Alex and Helmut Goldschmidt. We break away from the crowds surrounding Notre Dame to visit a sheltered spot on the eastern tip of the Ãle de la Cité, the

Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation

. A guard allows us to descend a steep flight of concrete steps that leads us nearly to the level of the Seine, although vertical bars of concrete impede our view of the water flowing gently by. The focal point of the memorial is a crypt illuminated by two hundred thousand little pieces of glassâone for each of the deported soulsâthat somehow sparkle in the gloom. So close to the life-giving river and to the soaring majesty of the cathedral, we are nonetheless isolated and cut off from the city's bustling humanity. So, too, were the victims this somber place remembers so tenderly.

By Saturday, we are ready to fulfill the purpose of this pleasure tour of Paris, the decidedly unpleasant side trip to the suburb of Drancy. We are to be joined on this journey by a recent acquaintance I made at the beginning of the year due to an unexpected e-mail.

Over the Christmas holidays of 2010, I heard from the publisher of

The Inextinguishable Symphony

that an Ingrid Janssen had written to me from an address in Paris. In January, we began a correspondence and I learned that she is a few years younger than me, that she was born in Oldenburg, and that her father, like mine, was born in 1913. She wrote that she had discovered my book and learned some things about her hometown that both fascinated and dismayed her. Now she lives in Paris with her husband, working as a television and documentary film producer. When I told her about our visit to Paris and its grim purpose, she and her husband Jacques offered to drive us to Drancy.

So on Saturday morning, we meet Ingrid and Jacques in the lobby of our hotel. They are a striking couple, both tall and trim, she with shaggy blond hair, he with receding grey hair and a close-cropped beard. Both wear fashionable leather jackets. We climb into their Saab and off we go, Jacques at the wheel, winding our way along wide boulevards and increasingly narrow streets as we approach the northeastern suburbs. The shops are now less chic, the cafés and small electronics outlets we pass often identify themselves with signs in Arabic, Farsi, and Turkish. Our conversation, sparse to begin with, falls nearly silent.

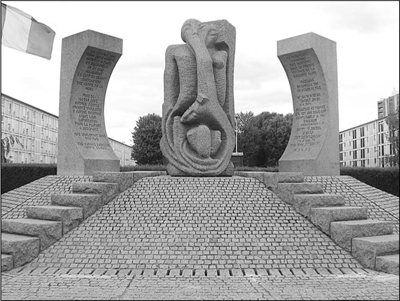

Jacques pulls the car to the curb and announces solemnly, “Here we are.” We emerge and walk slowly across the busy street to stare up at a deeply moving memorial sculpture created by Shelomo Selinger in 1976. Made of weathered pink granite, the sculpture comprises ten anguished human figures flanked by two curved surfaces on which are carved passages in Hebrew and French. On the left is a brief description of the murderous legacy of the Drancy camp. On the right is a quotation from the Book of Lamentations: “Is it nothing to you, all you who pass by? Behold, and see if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow.”

I

T WAS DESIGNED TO BE A QUIET REFUGE

from the hurly-burly of urban life. Architects Marcel Lods and Eugène Beaudouin conceived a modernist plan that featured some of the first high-rise apartments in all of France, embracing a tree-lined courtyard of grass and ample flower beds. According to its architects, peace would reign within

this horseshoe design of gentle residential living, and to prove it they bestowed upon their creation the name

La Cité de la Muette

, or “The Silent City.”

Shortly after the armistice of June 1940, the German invaders confiscated the entire complex and, surrounding the Silent City with barbed wire, converted it first into a police barracks and then into a detention center for holding Jews and other undesirables. But it was the French police who marked the most notorious use of the Drancy camp by conducting a series of raids throughout Paris in late August 1941 and incarcerating more than four thousand Jews within the apartment complex that had been designed to accommodate about seven hundred people. For nearly two years, the Drancy camp was guarded entirely by French

gendarmes

, who exhibited an appalling disregard for the abject suffering of the inmates. Food was scarce, hygiene was nonexistent, and there was no defense against the onset of cold weather. A prisoner who managed to scribble a note to relatives described the conditions at the camp in three short, brutal phrases: “Filth of a coal mine. Straw mattress full of lice and bedbugs. Horrid overcrowding.” By early November 1941, more than thirty inmates had died, and even the German military authorities were moved to order about eight hundred prisoners released for health reasons. Following the

Vél d'Hiv

roundup the following summer, more than seven thousand soulsâmen, women, and childrenâwere crowded into the seven high-rise apartment buildings. From the top floors, it was possible to see the skyline of Paris a few miles to the south, a view dominated by La Basilique du Sacré Coeur in Montmartre. But true civilization was miles and miles away.

Beginning on June 22, 1942, convoys of trains began departing from Le Bourget station, about a five-minute bus ride from the Drancy camp, heading for the extermination centers of Eastern Europe. At first, the orders from Berlin prohibited the deportation of children under fourteen, so mothers, fathers, and older siblings were frequently separated from their younger family members. Bewildered and terrified, children as young as five or six years old were forced to wave goodbye to their parents and then try to survive the horrors of Drancy on their own. A story began circulating that soon the children would be joyfully reunited with their families at a mysterious place called Pitchipoi. In early August, orders from Berlin allowing deportations of young children having now arrived, the journeys to Pitchipoi could commence.

“Behold, and see if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow.” The memorial sculpture by Shelomo Selinger that stands at the entrance to The Silent City

.

By the time the last convoy left for the East, on July 31, 1944, nearly sixty-five thousand Jews had been deported from Drancy. Approximately sixty-one thousand were shipped to Auschwitz, another thirty-seven hundred to the Sobibor extermination camp. Fewer than two thousand survived.

Alex and Helmut Goldschmidt arrived at Drancy on Thursday, August 13, 1942. They did not stay long. Almost immediately after their arrival in the apartment complex, on the morning of Friday, August 14, they were ordered onto a bus for the brief ride to Le Bourget. Once there, they were again loaded onto cattle cars along with nine hundred eighty-nine other Jewish prisoners, of whom about one hundred were

children under fourteen. It was Convoy Nineteen, the first of the transports from Drancy that included young children bound for the happy land of Pitchipoi.

S

ATURDAY

, J

UNE

11, 2011. Behind the Selinger sculpture, a railroad track intersects with a second track, on which a single boxcar stands, representing the thousands of cars that departed from this place during those two hellish years, each car filled to capacity with human beings, their journey made all the more unspeakable, if such a thing is possible, by the fact that some of the passengers on those trains were little children who were eagerly looking forward to a reunion with the parents who had been torn from their grasp a few weeks earlier and who by now had probably disappeared up the chimneys of the smoking crematoria hundreds of miles to the East. I scan the ground for a stone to hurl at the boxcar in front of me, but on either side of the pathway is only a well-tended lawn, and on the edge of the lawn a trimmed hedge, and, overhead, a French flag that flaps softly in a gentle breeze. There are no weapons at my disposal. And what good would it do, anyhow?

On the other side of the memorial lies the Silent City, looking pretty much as it did on that August day in 1942 when Alex and Helmut passed through. Here is the horseshoe-shaped apartment complex and here is the little tree-lined park in the center. “Who in God's name would

want

to live here?” I ask Amy, Ingrid, and Jacques. They shake their heads, although Jacques points out that, by the look of things, it's a fairly poor neighborhood and the inhabitants may not have too many choices of low-cost housing in greater Paris. It's true: the complex has the look and feel of many “urban renewal” projects of 1960s America, and it's probable that many of those who call this place home would prefer living elsewhere. But what a ghastly history to come home to every evening.

For the next ten minutes or so we walk slowly around the horseshoe, sometimes looking closely at doors leading into the apartment buildings themselves, once to note a small plaque that someone has affixed to a wall in memory of the French poet and painter Max Jacob, who died

here in the Drancy camp in March 1944. I find it next to impossible to believe that I am standing where my grandfather and uncle stood in the midst of their agony sixty-nine years ago, and I feel that familiar numbing sadness that I have come here much, much too late to help them. I say nothing but hold tightly to Amy's hand as we walk. When we complete our circular journey and stand once more in the shadow of the boxcar, I am overcome and hold my wife tightly as I weep.

After a minute, I lift my blurry eyes to the sculpture and find myself whispering, “No . . . there is no sorrow like unto my sorrow.”

I turn then to apologize to Ingrid and Jacques for my emotions and see them in an identical embrace. Ingrid, through her tears, says to me, “Do you know why I tried to get in touch with you last year?” I shake my head and after a long pause, she begins to speak.

“I was born in Oldenburg, but I left after high school in 1973. When I lived there, nobody ever spoke about the Jewish history of Oldenburg. Oh, we learned about âHistory,' what had happened in Berlin and Munich and Nuremburg, but it was taught to us as something abstract, something that had happened far away and had nothing, nothing to do with us. And so I never connected this âHistory' to my personal environment.”

Ingrid turns away and seems to be regarding the French flag as it defines the suddenly brisker wind that swirls over our heads. When she resumes her story, her voice is harder, colder.

“Then I read your book and learned what had happened in my home town on the Crystal Night. Something made me write âJuden+Oldenburg' in my Google browser and then I discovered more of the dark part of my hometown, things I had never heard about or imagined had happened so close by.”

She turns to me, starts to speak, but then looks away again.

“The next time I went home to Oldenburg to see my fatherâhe was born in 1913, so he was twenty-five in 1938âI asked him about Crystal Night. Where was he? What did he do that night? What did he know about the march through the town of the arrested Jewish men? He must remember! The newspaper must have written about it! What happened? What?

What?

”

Ingrid, suddenly aware of her raised voice, lowers her head and thrusts her hands into the pockets of her leather jacket. When she speaks again, there is weariness in her tone, as if she has said these words to herself many times before.

“His answer was like so many answers I have heard from him over the years, from him and from others . . . evasive, secretive, silent. I couldn't get him to the point. He didn't listen to me. He didn't want to listen.”

She takes a deep breath, and when she starts up again, the words tumble forth in a rush.

“Then he told me about a school friend, a friend named Alex Goldschmidt, who escaped to America. He said they were both musicians and played together in his former school orchestra. And he told meâI was so very surprised when he told meâabout a meeting in Oldenburg in the late '60s with former inhabitants of the city who had been thrown out by the Nazis. He went to this meeting in hopes of finding Alex, but he was informed that Alex didn't have the money to come back to Germany to attend this meeting.”

“But Alex could never have come to that meeting in Oldenburg in the late '60s. He got on a train here in Drancy in 1942 and never came back. He never came back!”

Ingrid looks at me with infinite sadness. “My father was like so many Germans of his era. He was a Nazi. He was a soldier and a Nazi. Did he try to embellish the past? Did he confuse your grandfather with your father? He never mentioned Günther, only Alex Goldschmidt. When I read your book, I was struck by the similarities with your father, that he was a musician, that his parents had a clothing store in the central city, that he was the one who escaped to America.

“My father died in 2009, so there will be no answers to my questions. I will never know if he really knew your family. That is why I wrote to you. If you miss pieces of a puzzle, even if you know that some pieces are lost forever, you always try to find the pieces next to them in hopes of getting an idea of the whole picture.”