Alex's Wake (42 page)

Authors: Martin Goldsmith

The Banquet of Nations, one of the remarkable frescos painted by one of Camp des Milles's inmates more than seventy years ago, now on display in the museum's Room of Murals

.

One painting depicts a procession of blue-skinned figures bearing plates that groan under the weight of immense sausages, cheeses, artichokes, and succulent fish, while others carry overflowing barrels of wine. Another wall features the words

“Si vos assiettes ne sont pas très garnies, puissant nos dessins vous calmer l'appétit,”

or “If your plates are not very full, may our drawings calm your appetite.” The most imposing painting, called

The Banquet of Nations

, offers a droll echo of Leonardo da Vinci's

Last Supper

, with men representing many nationalities dining on dishes from their various homelands: an Italian with a forkful of spaghetti, a Chinese man eating rice with chopsticks, an Inuit consuming blubber, an Indian in a turban swallowing fire, an Englishman in the guise of Henry the Eighth about to enjoy a plate of roast beef.

The Banquet

's painter was soon to be murdered in Auschwitz.

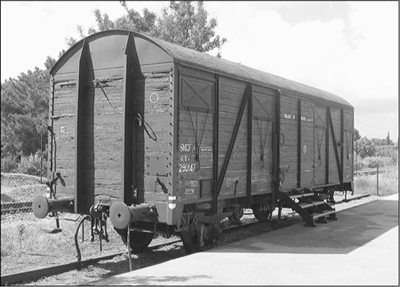

At this point, Katell concludes our tour by leading Amy and me out of the gates of Camp des Milles and along a roughly quarter-mile path to a railroad siding containing a single boxcar from a 1940s-era train. I am intensely aware that at this moment, for all my figurative travels these past weeks in the footsteps of Alex and Helmut, I am quite literally walking the same Via Dolorosa they followed on August 10, 1942. Did they know their fate, I ask myself numbly. As if reading my mind, Katell points back to the factory and tells us that during those terrible days in August and September when about two thousand people were shipped to Drancy, dozens of inmates, who could clearly see the teeming siding from their vantage point, chose to jump to their deaths from the factory's top floor rather than join the majority.

The single boxcar that stands at the railway siding at the museum, representing the trains that transported roughly two thousand prisoners to Drancy in the summer and fall of 1942

.

Katell swings open the door to the boxcar and we step inside. It's a bright warm day, but probably no more than seventy-five degrees. Even so, it is stiflingly hot within the car, and we are only three. I try to imagine what it would feel like to be among more than a hundred people jammed together with the door sealed shut, the boxcar standing still all night before beginning its journey northward. And my grandfather and uncle among the damned.

Fearing that I might sink to my knees and start to weep, I stumble out the door and back onto the safety of the siding. My mind suddenly rings with those words of warning and remonstrance sent by Alex and Helmut to my father in the New World: “I think the worst of the horror is still to come.” “It is almost unnatural that you found no time to write us.” “Do everything you can to get us out.” “I can't understand why you spent two days in Philadelphia but couldn't spend two hours in Washington.” “If you don't move heaven and earth to help us, that's up to you, but it will be on your conscience.”

Those words resound like curses, and I clasp my head in my hands and stagger down the siding to a low iron fence, trying to squeeze them from my memory. I am suddenly furious with my father for his inattention and neglect, and then a moment later, awash in pity for the unbearable guilt he must have carried to his dying breath. Trying to think of anything else, I recall Helmut's repeated requests for stamps . . . and then remember how my father helped me start my own stamp collection when I was a boy, how he would often come home from work with little clear plastic packages of commemorative stamps from faraway lands like New Zealand, Egypt, or Togo. Was he trying, in a feeble way, to redeem himself?

At that moment, in that terrible place, I feel my father's guilt bore into me. It hurts like a shard of jagged glass rasped against my flesh. But excruciating as it is, I realize to my shock that it is also painfully familiar. I know this feeling, I tell myself, as well as I know my reflection in any mirror. And I have known this feeling for as long as I can remember. It has brought me here, far too late for me to do any good. My father failed to save his father and his brother. I have failed to save my grandfather and my uncle. This is my inheritance: failure, sorrow, and guilt.

Amy is once more at my side, and hand in hand we begin a measured walk back to the old brick factory. But our steps only heighten my grief, as I reflect that Alex and Helmut were not afforded the choice of walking this path

away

from the boxcar. I am reminded of the passage in

Catcher in the Rye

when Holden Caulfield recalls his brother Allie's funeral and then savagely says that it began to rain and all the mourners hurried off “someplace swanky for lunch,” leaving Allie alone in his grave. I tell

myself that there is nothing I can do to alter this unspeakable history and that it will do no one any good if I rend my garments or sleep every night on a bed of nails out in the rain. But I feel such helplessness and exhaustion in the face of so much cruelty, ugliness, and depravity. All I can do, I conclude, is to resume the journey, to keep on following my relatives until the end. And then to tell their story.

We bid farewell to Katell and wish her well, along with her colleagues, and return to the Meriva. I avert my eyes from those of Alex and Helmut as they gaze accusingly at me from their place above the rearview mirror, and we drive slowly away.

On September 10, 2012, exactly seventy years after the last train left Les Milles bound for Drancy, the memorial museum was dedicated and officially opened by French Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault.

T

UESDAY

, J

UNE

7, 2011. There is something about a long drive in an automobile that comforts the spirit. Long before the internal combustion engine, Herman Melville's Ishmael warmed the damp, drizzly November in his soul by taking to the sea. In our day, Jack Kerouac understood that all he really needed for solace was “a wheel in his hand and four on the road.” This morning, we back Jack. As I steer our little Meriva northward along the French autoroute system, my blues of yesterday seem to recede further with each passing mile. The hum of the tires, the pleasant vibration of the steering wheel, the unfamiliar landscape unfolding before us, and the mellifluous names on the road signs as they flash past all contribute to a sense of adventure and possibility, the best rebuke to the feelings of futility and dread that enshrouded us in the shadow of the brick factory. Although the next stop on our itinerary is the sad suburb of Drancy, we will get there by way of one of the jewels of our civilization, the sparkling city of Paris. On this bright morning, on the move, we are happy once more.

Having learned from the letter Alex wrote in Agde about his stay in the Central Hospital in Contrexéville, I have decided to pay a return visit to that charming little city on our way to Paris. Under sunny skies, we speed north as far as Lyon and then bear to the northeast. By late afternoon, we reach Contrexéville and decide to spend another night at the Inn of the Twelve Apostles. Its proprietor, a garrulous native of Italy

who has called Contrexéville home for decades, is surprised and pleased to see us again. After a long day on the road, we are more than happy to avail ourselves of his hospitality.

Early the next morning, we pay a call on the town's

Mairie

, or city hall, where we make inquiries regarding the existence of a Central Hospital in the winter of 1939â1940, the months Alex mentioned in his letter. A helpful young woman named Audrey Hestin tells us that there was no community hospital in Contrexéville during that period, but that one of the town's hotels had been temporarily converted into a military hospital in the months following the start of the war. She suggests we visit the national military archives, which are located in Vincennes, just outside Paris, to see if theyt have any record of Alex's convalescence. Before we leave town, we pay a call on the building that once housed the hotel in question. Now a professional school that instructs its students in hair design and restaurant and hotel management, the four-story structure looks across the main thoroughfare to the trees and fountains of the thermal park. We spend a few minutes walking through the halls, as I wonder which of the rooms might have sheltered Alex with a mattress and warm blankets, the last actual bed he would ever enjoy.

We then return to the road, making our unhurried way along a pastoral byway through the town of Chaumont, where we again buy some crusty bread and flavorful

fromage

for a pastoral lunch in a green field. Soon after, we say our farewells to the leisurely pace of the countryside, as we merge into the steady stream of traffic on an autoroute bound for Paris. We spend that night in a forgettable motel in what amounts to a truck stop on the distant outskirts of the capital city and arise on Thursday morning filled with the excitement of knowing that this very day we will see the legendary City of Light.

Thanks to more extraordinary navigating by Amy, we drive safely through the traffic-choked Parisian bypass to the remarkable Château de Vincennes, just east of the metropolis. Dating back to the fourteenth century and built largely by King Charles V, the castle featured the tallest fortified tower in all of medieval Europe. It was a lavish residence for French royalty for centuries, until Versailles became the favored location

in the years leading up to the Revolution. The château was later converted to a state prison, whose most famous inmate was the Marquis de Sade. In recent years, it has housed the archives of the French military. After walking slowly through the cobblestoned courtyard, admiring the architectural glories of the old castle, we present ourselves at the

Service historique de la défense

and pose our question. Once again, we are disappointed. The French armed forces have no record of a military hospital in Contrexéville and no record of coming into contact with Alex Goldschmidt in the winter of 1940. I resign myself, for now, to never learning the details of how my grandfather spent the winter after being expelled from his relatively Edenic existence in Martigny-les-Bains.

Fortunately, the Château de Vincennes is a relatively short drive, even in midday Parisian traffic, from our hotel, located on the Rue de Faubourg Saint-Antoine in the 11th

arrondissement

. We squeeze the Meriva down an impossibly narrow passageway to a spot in an underground garage, check in, and immediately make arrangements to meet my cousin Deborah Philips and her partner, Garry Whannel. Actually, to be absolutely genealogically correct, Deborah and I are second cousins once removed, on my mother's side. Both my mother, Rosemary, and Deborah's father, Klaus, grew up in the German city of Düsseldorf. They were close to the same age, but the generations were somehow scrambled and it was Klaus's mother who was Rosemary's first cousin. Since my family is so smallâand because I like Deborah and her sister, Claudia, so muchâI've always operated on the shorthand assumption that we're simply cousins and left it at that.

Deborah grew up in London, but her father often traveled to Paris on business and frequently took Deborah along, resulting in Deborah's long-standing love affair with Paris and her near fluency in French. A few years ago, Deborah, a professor of literature and cultural history at the University of Brighton, purchased a small

pied-Ã -terre

in Paris, and she and Garry spend several weeks every year in France. They have offered to show Amy and me the town. We are delighted.

For four days, they squire us around the city of which Victor Hugo wrote, “Nothing is more fantastic. Nothing is more tragic. Nothing is more sublime.” We discover that nothing can compare to seeing Paris by

foot and Métro, as Deborah and Garry lead us on a walking tour that encompasses the Champs Elysées and the Place de la Concorde, the Seine with its bridges and bookstalls where Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron danced in

An American in Paris

, the Pompidou Center, the Opera, the Musée d'Orsay, the Jardin des Tuileries, the Cathedral of Notre Dame, and the cathedral of books and ideas that is Shakespeare and Company. One afternoon when Amy and Deborah go shopping, I make my solitary way to the Père Lachaise Cemetery and visit the graves of Chopin and Bizet, Poulenc and Cherubini, Balzac and Sarah Bernhardt, Delacroix and Molière, Edith Piaf and Jim Morrison and Oscar Wilde. At night, Deborah and Garry introduce us to the finest out-of-the-way restaurants they have discovered on their personal culinary journey and also, at my request, join us for a meal at

Le Boeuf sur le Toit

, that hangout of artists and their hangers-on during the dancing decade of the 1920s. We agree wholeheartedly with Thomas Jefferson, who declared that “a walk about Paris will provide lessons in history, beauty, and the very point of life.”