All the King's Cooks (19 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

36.

The Great Cellar

Here, beneath the Great Watching Chamber, ail the wine was kept for the household. A yeoman treyer would tap the casks when needed by boring a hole in the end with his auger and driving in the tap; he would use a gimlet to bore the hole in the top to receive the spile-pin.

The privy cellar was probably used for sweetening and spicing wine to make hippocras, the digestive taken by the King at the end of his meals. For small quantities, the spices were put into a conical filter-bag of felted woollen cloth – its shape supposedly resembled the sleeve of Hippocrates, the celebrated Greek physician. A pint (575ml) of wine was poured into the bag, followed by a pint of sweetened wine – then it was all poured back through the bag until it ran perfectly clear. For larger batches, beaten spices would be mixed in a gallon (4.5 litres) of wine in a pewter basin, and a sample run through the first two filter-bags in a row of six suspended from a bar; then the spicing of the main batch would be corrected as necessary and the whole batch passed through all six filters, after which it was poured into a vessel and sealed down until ready for use.

7

The malt liquors served at the palace included ale and beer: ale, the weaker brew, was probably still flavoured with herbs at this time. To ensure that the beer, the stronger, hopped drink, was well brewed, John Pope the King’s beer brewer called upon continental expertise – he was allowed to retain twelve foreigners in his house ‘meet for the said feat of beer brewing’.

8

The purveyors tasted the ales and beers at the brewhouse, and supervised the groom versours while they set the barrels on their stillages in the beer cellar (no. 53). From here the liquor was drawn into leather jugs that would then be passed out at the hatches of the privy buttery (no. 57) and the great buttery (no. 58), as called for.

The grooms of the pitcher house would carry the ale and beer from the butteries and the wines from the cellar bars upstairs, where they were served by yeomen of the pitcher house, using cups of the appropriate status issued to them by the sergeant of the cellar.

9

Since some of these would have been used to serve the bouche of court the previous evening, the pitcher house staff had to ‘fetch them home’ every morning, and carefully count them to check that none had gone missing and that there were enough for everyone at dinner. They were

then washed ready for use, and dried with worn-out linen cloths supplied by the Ewery.

The Ewery was the department that dealt with all the table linen and handwashing equipment. It received its cloth by measure from the Counting House, and its silver or gilt basins and ewers, as well as napkins decorated with these precious metals, from either the Treasurer of the Household or the Jewel House, for use in the chambers and Hall.

10

Just to the south of the Lord’s-side kitchen and linked to it by a doorway lay the Scullery Yard (no. 37), the ‘Little Court’ used by the officers of the scullery. Except for the Henrician south wall it was all built by Cardinal Wolsey, probably soon after 1515. The Scullery was essentially the palace’s hardware and tableware department. Its sergeant, clerk and twelve yeomen, grooms and ‘children’ were responsible for the purchase, safekeeping, maintenance and replacement of all the tubs, trays, baskets, flaskets, chests and standards used here, and the brass pots, pans, spits, oven-peels and so forth used by the kitchen staff, which cost an estimated £66 13s 4d each year.

11

They also bought in the ‘herbs’ used in the kitchen – this word then including vegetables of all kinds, rather than just the medicinal and flavouring plants we would now call herbs. These cost £40 a year.

Among his various duties, George Stonehouse, the clerk of the scullery at this time, had to record the supply of tableware used in the Hall and chambers.

12

Recasting and reworking the pewter vessels used in the Great Hall, incorporating the metal of those that had worn out or broken, reduced the cost of supplying the dishes by about half, but it still came to £40 a year. The pewter scullery (no. 36) was probably located on the west side of the Scullery Yard. From here timber-framed hatches were cut through Wolsey’s brick walls into the hall-place dressers so that the dirty dishes returning from the Great Hall could be efficiently passed inside, all under the watchful eye of the clerks in the dresser office directly opposite.

37.

The Scullery Yard

Built by Cardinal Wolsey shortly after 1515, this yard lies just to the south of the Lord’s-side kitchen. The pewter scullery is in the building to the left, and the Lord’s-side dresser office in the one to the right.

The silver dishes issued from the Lord’s-side dressers were supplied to the Scullery by the Jewel House. Having been used in the Council and Great Watching Chambers, they may have been returned through the same hatches as the pewter, but this seems unlikely because mixing up cheap pewter with expensive silver would make it very difficult to maintain its security and prevent it being damaged. However, the 1674 lodging survey describes the room at the south-west corner of the Great Space (no. 43) as the Lord Chamberlain’s scullery. Its position in the Great Space, its large dresser hatch and its proximity to the Lord’s-side kitchen dresser hatches would certainly make it most suitable for issuing

and receiving the silver dishes as they passed between the kitchens and the chambers.

The dishes would be washed and cleaned in the pewter and silver sculleries, the polishing material most probably being whiting, a soft ground and washed chalk, which was supplied in balls, the Althorpe accounts including payments for ‘12 balls of whiteing to scowre the plate’.

13

Made into a paste with a little water, and rubbed on with pieces of worn-out table-linen from the Ewery, it would polish with minimal scratching; the plate would then be rinsed and dried with clean cloths.

14

Serving the King

A Royal Ceremony

By combining evidence from royal ordinances from Edward IV’s to Edward VI’s time, comparable household regulations and instruction manuals, it is possible to gain some idea of how the meals were served at the palace.

In a period when personal timekeeping devices were of the greatest rarity, and given that the faces of the astronomical clock in the central Gatehouse were not visible to all, it was essential to devise some foolproof method of informing everyone of mealtimes. For this reason the minstrels were instructed to go ‘blowing and piping, to such offices as must be warned to prepare for the King and his household at metes and soupers, to be the more ready in all servyces, and all these sitting in the hall togedyr, wherof sume use trumpettes, sum shalmuse [shawms, instruments of the oboe class, with double reeds in a globular mouthpiece] and small pipes’, and they were provided with ‘a torch for wynter nyghts whyles they blowe to souper and other revelles’.

1

This tradition was continued by Elizabeth I – for whom twelve trumpeters and two kettle-drums made the Great Hall ring for a whole half-hour before the Yeomen of the Guard carried up her meals. Playing from the gallery over the screens entrance to the Great Hall, they could not fail to alert everyone in the neighbouring offices, while remaining well out of the way of bustling servants preparing the tables on the floor below.

Preparations for serving the King began with the sewer, the King’s master cook and the doctor of physic together deciding his menu.

2

The surveyors of the dresser, Edward Weldon and Eustace Sulliard, then had to make sure that all the king’s food was of the very best and that it was safely and cleanly handled from the time it was received from the larders by the master cook for the king’s mouth through to its appearance at the dresser of the Privy Kitchen.

3

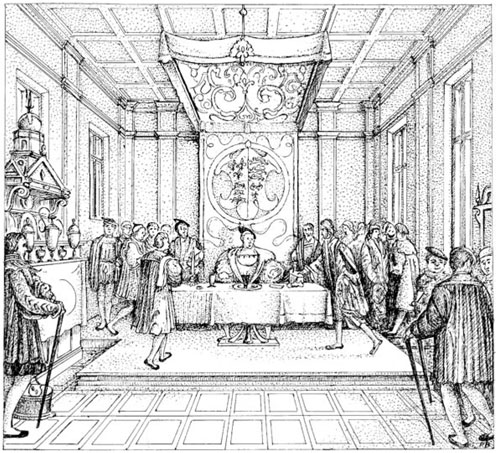

38.

Serving the King

In this drawing, based on an original probably of the early seventeenth century, Henry VIII is being served by the staff of his Privy Chamber; the arrangement of the canopy of estate, the dais and the standing cupboard with its display of gold plate is clearly shown.

In the 1540s Henry usually dined in private either in his Privy Chamber or in his secret lodgings – rooms for which neither the ordinances or any other source can provide any meaningful

practical information. On some occasions, however, especially when he was entertaining ambassadors and other important guests, he used the Presence Chamber. Here his table would be set up, probably by the gentlemen ushers of the privy chamber clad in their livery coats, each of which took ten yards (9.1m) of crimson velvet.

4

George Villiers, sergeant of the ewery, or his yeoman ewerer for the King’s mouth, would now lay a tablecloth of white linen worked in damask with flowers, knots, crowns or fleur-de-lis.

5

He also provided the damask linen towels and the magnificent ewers, lavers and basins used for hand-washing, all made of gold, gilt, glass or marble. One basin, for example, weighed a massive 332 ounces (9.4 kg) and incorporated a fountain in the form of three women who spouted water from their breasts.

6

In cold weather the groom for the King’s mouth heated the water beforehand, in a chafing dish kept specially for this purpose.

7

Now the sewer, Lord Thomas Grey, Sir Percival Hart or Sir Edward Warner, and the carver, Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, Lord William Howard or Sir Francis Bryan, would be armed with linen towels, each measuring 9 feet 9 inches (nearly 3m) by four and a half inches (11cm) wide. The sewer would probably hang his around his neck like a stole, while the carver would place his over his left shoulder and knot it at his right hip before setting the salt, the trenchers, the gold-fringed napkin, the cutlery and the manchets from the pantry all in precise positions on the tablecloth.

8

All these utensils were of fabulous quality: the salts made of bejewelled and enamelled precious metals, or ivory, jasper, agate, beryl, chalcedony or rock crystal, and incorporated features such as clocks or fountains.

9

The trenchers were small silver, silver-gilt or marble plates, some with a recess for salt sunk into one corner.

10

Even the bread was wrapped in a ‘cover-pain’ of richly embroidered and gold-fringed linen, or brilliant orange and white silk fringed in white and gold.

11

When the King informed the Chamber that he wished to dine, the sewer took the gentlemen ushers down to the privy kitchen dresser, returning with the first course in a procession which on days of estate was headed by a sergeant at arms, probably with his gilt mace, the Comptroller, the Treasurer, the Lord Great

Master – all with their white sticks, the latter side by side with the Lord Chamberlain if he was present, then the sewer and the gentlemen ushers.

12

All the serving dishes were of massive silver gilt: chargers weighing around 80 ounces (2.3kg), platters in sets of twelve of around 35 to 50 ounces (990–1400g), and dishes, also in dozens, of around 25 to 30 oz (710–850g).

13

There were sets of twelve saucers, too – smaller, round vessels of about 8 to 12 ounces (225–350g), to hold mustard and similar sauces to accompany the main meats and fish. The first course would include pottages, brawn, stewed beef, mutton, pheasant, swan and capon, baked venison, blancmange, custard, jelly and fritters, for example, while the second comprised all manner of roast game, perch in jelly, doucets, leaches, cream of almonds and so on.

14

Having instructed the ushers where to place each of the dishes on the table, the sewer would go to the ewery table at one side of the Chamber and say to the ewerer, ‘Give me a towel that the King shall wash with.’ He would then lay the towel on his shoulder and go into the privy chamber, followed by an usher with a basin, then present the basin to the highest-ranking person present – an earl or baron on a day of estate – who then held it in front of the King as he washed.

15