All the Presidents' Pets (13 page)

21

Vest in Show

Â

There were three things that I had expected would happen immediately: Firstly Eric Sorenson called to confirm that, yes, I had committed strike two and I had one chance left before my press credentials were stripped. Secondly my East Room antic made the CNN and Fox News crawls and I became a pariah in the press corps. Even Candy started avoiding me.

So it came as a pleasant surprise that ThirdlyâLaura Bush asking for my exile to Guantánamo Bay under the third Patriot Actâdid not come to pass. She told the ATF agents that I was “simply enthusiastic, like a child with his very first book, alive with curiosity.” She even sent me a copy of

The Brothers Karamazov

written for children.

The next day I paid a visit to Scott McClellan in his office, which lay tucked between the Briefing Room and the West Wing offices. I came to request a private sit-down interview with Barney.

After he finished laughing, I asked again. “You know, Scott, you may think I don't deserve a one-on-one with Barney after what happened yesterday. And I can understand that, I suppose. But it doesn't look very good when Fox News is the

only

network that ever gets access to the First Dog. There's an election coming up and it might behoove you to spread the wealth.”

Even in my compromised state I could prick Scott on this point. “That's not fair!” he shot back.

“Or balanced, I know, but one has to ask why nobody other than Laurie Dhue gets access.”

Scott averted his glance, then began shuffling papers on his desk. “Well, Mo, right now there are special restrictions on Barney.”

“Restrictions?”

“That's right, so I'm afraid you can't see him.” Scott still wouldn't look at me directly.

“Well, what kind of restrictions? Scott, this is my beat. I should know.”

Scott finished messing with his papers, then looked me right in the eye. “Perhaps if you'd read Bob Novak's column this morning, Mo, you'd know that Barney has rickets.”

“What?!” Rickets, a disease marked by the softening of the bones, was the result of malnutrition.

“I don't know anything else, so don't ask.” Scott anxiously resumed his shuffling. He seemed nervous.

“Scott! You can't just drop something like that and expect me to not ask questions. Dammit, what's going on? Barney looked perfectly fine yesterday.”

“Apparently someone leaked it,” he said. “All I know is that it's true.”

I hadn't read Novak's column that day. “Gee, I can't imagine who leaked it.”

“Neither can I,” said Scott, almost defiantly. “Now if you please.” He picked up his stack and moved toward a thin closet just by the office door. I couldn't let him leave just yet so I stepped between him and the closet.

Scott lowered his chin. “Now, Mo, you don't want to make me late.” He shot a glance toward the doorway. Gephardt the Albino was standing right there, looming, arms crossed and menacing. I instinctively moved away, barely able to suppress a shudder.

Scott opened up the closet door and reached for his jacket. Inside, hanging next to the jacket, was a blue satin vest.

“That's the famous press secretary's vest, isn't it?” I asked. The legendary vest had been passed from secretary to secretary. Supposedly there was a note placed in the inside pocket and passed down. The contents of that note were unknown to anyone else.

Gephardt the Albino shot me an arctic-cold stare.

Scott shut the closet door and put on his jacket. “Your mother must have had a tough time keeping your hand out of the cookie jar,” he said without affection. “Sorry this meeting had to end so abruptly.”

Once again I left with more questions than answers. Whether or not Barney actually had rickets, this felt eerily like an attempt to push him out of the public's view altogether. It was something that Mr. Peabody had suggested might happen.

22

Dick Morris's Feet

Â

Any good reporter has more than one source for a big story. And this was turning out to be the biggest story I'd ever hoped to cover.

I'd chosen to believe the core of what Helen and Mr. Peabody had told me. Pets and Presidents, I was willing to accept, were tied to each other by virtue of an ancient pact originating with Cincinnatus and his horse Sadie. To this day the President received advice from his pet.

But the inner circle surrounding the President jealously guarded their influence with the Commander-in-Chief. Over time the pet had become marginalized and the clueless press had long ceased to offer protection. Now if the pet tried to fulfill its true responsibilities it faced grave danger. In Barney's case, the rickets leak might very well be more than rumor. I needed to ratchet up my investigation.

My first instinct was to track down Bob Novak. But he was tied down all day at the Fox-sponsored second annual

Culture War Games.

The event was, I had to admit, great television. Where else could you see Pat Robertson in a tank top? I had to tune in for at least a few minutes.

Team Traditionalist once again boasted an impressive roster. Conservative Congresswoman Marilyn Musgrave and Bob Jones III were unbeatable at the three-legged race. And the

Washington Times

's Tony Blankley ran the tires like nobody's business.

Team Secularist was more of a hodgepodgeâliberal thinkers, sitcom actors, convicted rappers, and child molesters all lumped together by Fox News. Team captain Eric Alterman, from

The Nation

magazine, objected to the composition of his team. But Team Traditionalist captain Bill O'Reilly was having none of it, “If you're not a traditionalist, you're a secularist, Alterman,” he bellowed, jabbing his finger with Robert Conradâlike fury into Alterman's chest. “So stop your whining.”

Team Secularist actually put up a decent fight. Naomi Wolf and Ludacris won the wheelbarrow race but then Dr. Laura Schlessinger tied it up with a lightning-fast performance on the monkey bars, after which Dr. James Dobson dumped a bucket of ice-cold Gatorade on her head in celebration.

Time was wasting, though. I turned off the TV and got back to work.

I needed to seek out someone who might have the goods on a former presidential pet and a very mysterious incident.

Buddy, Bill Clinton's four-year old chocolate Lab, was killed in January of 2002, less than a year after moving to Chappaqua. All that was known was that a seventeen-year-old girl, driving on a busy Route 117, struck Buddy, who'd reportedly been chasing after a van that had just left the Clintons' property.

The Internet had become rife with conspiracy theories about the death. Some speculated that Mrs. Clinton's former press secretary Maggie Williams had poisoned the dog with chocolate, then placed his body in the road to make it look like an accident. (Indeed traces of chocolate were found in both Buddy's

and

Vince Foster's bodies.) Maggie Williams, according to these sources, was also responsible for the death of Kurt Cobain. She apparently spent most of her time outside of the office.

What happened, I wondered, to Buddy and to his predecessor Socks the cat, whose exile from the West Wing was equally suspicious? I wasn't interested in hysterical speculation. For sober perspective I sought out former Clinton advisor Dick Morris.

I had only met Dick once before, at New York's Peninsula Hotel spa. I had been given a gift certificate for a deep-tissue massage. Dick was at the Peninsula for his weekly pedicure. He'd just successfully undergone “toe cleavage” surgery.

“They just shortened a couple of toes and lopped off a bunion,” he had explained. “Jimmy Choo is coming out with a men's line and damn if I'm not going to squeeze into them,” he had said.

It was early March 2001 so the Bush administration was less than two months old and people were still talking about the alleged trashing of the West Wing by outgoing Clinton staffers.

Dick had claimed to have the inside scoop: “You do realize what really happened, don't you? Bill Clinton invited some Arkansas state troopers over for his bon voyage. Naturally they brought along a busload of strippers. Things got out of control and everyone, including the President, started pouring Bartles & Jaymes wine coolers on the computer keyboards. Anyone can tell you that that destroys even the finest electronics.”

“I'm not sure I believe that the President would do that,” I had said.

“Don't kid yourself, I worked for Bill Clinton in the White House. I know how vindictive the man can be and I know his dietary habits. Who else do you think it was who smeared Big Mac special sauce all over the bust of Lincoln in the Oval Office? As I told Bill O'Reilly, the defacement of that image is an impeachable offense.”

“But Clinton was already impeached. How do you know any of this anyway? You broke with the Clintons long ago.”

“Just trust me. Hey, careful with the padding,” he had snipped at the pedicurist. “There's fresh collagen in there.”

This time around I caught up with Dick at the swanky Ilo Day Spa on Wisconsin Avenue in Georgetown. Ilo had been frequented by many high-profile Washingtonians, Monica Lewinsky and Tipper Gore, to name just a couple.

I found Dick getting a mud bath, his face covered by a towel. I sank into the next tub of mud before I called out to him.

“Well, if it isn't Mo Rocca. I read about your escapade in the East Room. You must have your tail between your legs,” he snickered. “What are you doing here?” Every time I saw Dick I couldn't help but think of what a great Mordred he'd make in a revival of

Camelot.

But I needed to stay focused.

“I'm here to detoxify,” I lied. “And I thought I might catch up with you.”

“Well, you've come to the right place. The peat-moss volcanic ash blend can't be beat. And the sloughing you'll get! Before I started coming here, I had skin rougher than Noriega's.”

“Interesting. So, Dick, I've been thinking. It's coming up on three years since Clinton's Lab Buddy died. It seemed innocent enough. Do you think there was any bigger story behind it?”

“Chico,” Dick called over to his young Mexican attendant.

“Mas, por favor.”

The attendant poured a couple of fresh buckets of mud on Dick as he began holding forth. “Let's be very clear about this. Nothing with the Clintons is as simple as it seems. There's always a bigger story.

“Remember that

Governor

Clinton's dog Zeke was similarly killed in 1990 in Little Rock,” he continued. “Mysteriously run over

after

Clinton had been successfully reelected.”

“You're suggesting that the Clintons didn't need Zeke anymore?”

“I don't suggest. I merely state facts. Chico,

agua,”

he directed the serving boy. He turned back to me. “Remember also that Buddy the Lab was acquired in December 1997, shortly before the Lewinsky scandal surfaced. The dog was certain to make Clinton more popular.”

“You mean Clinton knew that he'd be in legal hot water soon and wanted the dog as a diversion for the public?”

“Gracias,”

Dick said to the boy. He took a swig of water before Chico placed two fresh cucumber slices on Dick's eyes. “A diversion? Like the bombing of a Sudanese aspirin factory? I would

never

accuse the Clintons of something like that.” He laughed.

“Very interesting,” I said. “And what about Socks?”

Dick flinched. Although I couldn't see his eyes, I could tell he was bothered by the question. “What do you mean, âwhat about Socks'?”

“Well, Socks the cat was suspiciously exiled from the White House and placed under the supervision of Betty Currie and away from the press not long after Buddy's grand entrance. Whose decision was that?”

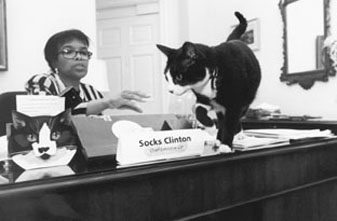

Clinton's cat Socks complaining to presidential secretary Betty Currie about changes in the White House, post-'94 midterms.

“I don't know,” he said abruptly. “The two pets probably didn't get along. So it was probably Buddy's âdecision,' as you say.” Dick laughed nervously.

Something wasn't sitting right. “No,” I said, “something tells me that Buddy's the patsy here. Something or someone else forced Socks to relinquish power.”

Dick was squirming in his mud. “Chico, bring me my bath sheet!” Dick stood up as Chico wiped him off. I looked away as quickly as possible. “I'm afraid the heat is getting to you, Mo.” Dick wrapped himself in Egyptian cotton, balanced himself on Chico, then ever so carefully stepped into his cashmere bunny slippers, grabbed his man-bag, and turned to me. “You know, when I hear wackos like you, I lose all faith in the system.”

23

When Good Presidential Pets Go Bad

Â

“I hope I didn't compromise you in any way, Helen, but I needed to investigate on my own,” I said. Helen, Mr. Peabody, and I were all sitting in Helen's lair. Today was Helen's molting day so she needed to take it easy.

“I believe I told you to be discreet,” sniffed Mr. Peabody, who was brushing out Helen's old feathers and collecting them in a pile on the floor. “It is extremely important that you give no one the sense that you may be privy to this kind of information.” Mr. Peabody was unusually agitated on this point.

“Now, now, Mr. Peabody,” said Helen, “I would never want Mo to accept the first answer he's given. That would be shoddy reporting.”

“As you like it, Madame,” said Mr. Peabody.

“Thanks for understanding,” I said. “I guess I just needed to see how different theories stack up.”

“Or you could just look at primary source material on the Clinton presidency,” said Helen. “Remember, all you have to do is ask. Mr. Peabody?”

Mr. Peabody handed me a copy of

All Too Feline,

an unpublished tell-all memoir by Socks the cat. The introduction was all I needed to read:

I was such an idealist when I first came to the White House. The Clintons were my kind of people, passionate about ideas and reform. We were going to change the world.

When I told the President to back the Oslo peace process with its prudent exclusion of any decision on the status of Jerusalem, he went ahead and invited Arafat and Rabin to the Rose Garden. When I told Mrs. Clinton about my urinary tract infection, she launched an unsuccessful but well-intentioned initiative for universal health care. All in all our first year in office was mixed, but we were optimistic.

I could overlook some of the President's foibles, like his Hollywood friends who were overrunning the place. Did Markie Post really deserve a private briefing on Haiti? What did Ted Danson really know about Somalia? It seemed at times that Linda Bloodworth-Thomason was the chief of staff. Please.

Designing Women

might have been a hit, but

Evening Shade

? Total crap. I can't believe that Charles Durning and Marilu Henner embarrassed themselves by appearing on that dud. You knew they'd really jumped the shark when Kenny Rogers made a cameo.

But then something happened that marked a darker shift. After the '94 midterm elections, a new kind of presidential advisor entered the scene. A practitioner of political black arts, a Svengali, also known as the Political Consultant. His name was Dick Morris and his first order of business was to exile me to the East Wing. Soon my role as First Pet wasn't worth a bowl of warm drool. Then one morning, after one of his mysterious overnight polls, he advised the President to co-opt the “Millie vote” by getting a dogâthis he called triangulation. (Overnight polls? Who the hell answers the phone at 4

A.M.

to answer Dick Morris's questions?)

In the end nothing was sacred, except of course that tartan dog bowl that I'd occasionally find press secretary Mike McCurry caressing.

“The manuscript caused quite some consternation in the Clinton camp,” said Mr. Peabody. “Mrs. Clinton never forgave him. But Socks felt he needed to write about some of the problems he saw in the White House.”

“It serves as a cautionary tale for White House pets who may enter office with high expectations,” said Helen. “They're entering in an increasingly precarious time.”

“Socks didn't allow himself to get used,” I said. “But are there good presidential pets who have gone bad?”

“Of course,” said Helen. “None of the American presidential pets have gone so far as, say, Hitler's sheepdog Blondie. That said, all too often a counselor to a presidentâsomeone who should give candid adviceâhas become a willing prop or shill for the administration.”

“That was Buddy's role, I'm afraid,” said Mr. Peabody. “To be a distraction in a swirl of scandal. He was not, by the way, murdered. So Mr. Scaife, if you're reading this, you can recall your private investigators from the Chappaqua Pet Morgue. Buddy's death was an accident.”

“The death of Warren Harding's Airedale Laddie Boy wasn't so accidental,” Helen said. “He too had cheapened his office by doing exactly what the administration wantedâplaying it cute for the press, sitting in a specially built chair in the Cabinet room for mock interviews with the

Washington Star.

It was adorable, all right, and it helped steal focus from the Teapot Dome scandal. After Harding died in 1923, Laddie Boy felt so guilty for shirking his responsibility that he killed himself.”

Mr. Peabody picked up here. “Then there are the pets who have enabled presidential inaction or delinquency, like James Buchanan's Newfie Lara. President Buchanan spent most of his ill-fated term in a state of emotional crisis over his breakup with former vice president William Rufus King. Lara simplyâ”

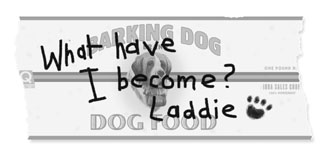

Warren Harding's self-loathing airedale, Laddie Boy, shortly before his sad end.

“Wait a minute, Mr. Peabody!” I said. “You're not implying that President Buchanan was gay. I've been to his estate Wheatland. I've heard all about the death of his first love, Ann Coleman. He was so heartbroken he was never able to love again.” The docent had nearly brought my mother and me to tears telling us that story.

“James Buchanan was about as straight as Dudley Do-Right,” said Mr. Peabody dismissively. “He lived with Mr. King when the two were senators. When King, then V.P. under Pierce, died after sailing to Cuba for vacation in 1853, Buchanan lost his marbles.”

“Sailing to Cuba? I didn't know they had gay cruises back then,” I chuckled.

Mr. Peabody gave me a withering stare. “I'm sorry, but open-mike night was last night.”

Laddie Boy's last note.

“Bitch,” I muttered under my breath.

“Buchanan went into a years-long tailspin,” continued Mr. Peabody. “Before seven southern states seceded in the last months of his term, Buchanan should have been making some hard decisions. That's what the Chief Executive is supposed to do. Instead he was going out till all hours on Dupont Circle, doing God knows what at clubs like Man-T-Bellums, hoping problems would solve themselves. It didn't help that he was high as a kite on wormwood poppers.”

“Major antebellum party drug,” explained Helen ruefully. “Lara helped him procure it.”

I glanced over at the infamous photograph of Jimmy Carter in a rowboat in a Plains lake, wielding his oar toward what he claimed was a rabbit menacingly swimming at him. The whole incident contributed to Carter's image as ineffectual in the face of any threat.

“You're interested in the âKiller Bunny' story,” surmised Helen. “Jody Powell really saved him on that one.”

President Carter ready to defend himself against a suicide (or homicide) nutria.

“Saved him?!” I said. Powell, Carter's press secretary, had casually mentioned the April 1979 incident to AP reporter Brooks Jackson the following August, then lived to regret it when the whole press picked up on it. This was hardly a favor. “Powell ended up giving the press and the Republicans a perfect way to make Carter look foolish.”

“You do learn slowly,” sighed Mr. Peabody. “Powell averted a major crisis. First of all the animal was in fact a nutria.”

“A nutria?” I asked. “You mean the reddish brown semiaquatic fourteen-inch-long rodent with webbed hind feet and razor-sharp teeth for cutting through plants?”

“Yes, the one with the cylindrical, sparsely haired tail and soft gray under-fur that in fact can grow to a length of three feet.” Mr. Peabody always needed to top me. “Kenny had been a presidential pet, living at the family's compound in Plains, Georgia, before falling under the spell of the Ayatollah Khomeini and becoming a radical Islamist. Out of safety concerns the Carter family expelled the nutria, renamed Khalid, which unfortunately remained in the area. Classified intelligence suggested that if given the chance, the nutria would do everything in its power to harm Carter. Diplomacy would not likely work.”

“So Carter had to use the oar,” I said. “But why would the administration intentionally leak this story?”

“To preempt a more damaging version of the story if it leaked through another source. Jody Powell knew the whole incident had the potential of revealing the power of pets. He rightly decided that marginalizing the animal with the mock sobriquet âkiller bunny' would cast the whole story in a âkooky animal tale' light that the administration could live with,” said Mr. Peabody.

“Those press secretaries are crafty,” said Helen. “They share their secrets only with each other.”

“That's right,” I said. “Speaking of which, do either of you know what's written in the note passed on through the traditional press secretary vest?”

“Oh, that is something that even I'm not privy to,” said Helen.

Mr. Peabody remained silent on this count, then suddenly spoke up. “I really must continue cataloging,” he said. “Madame, if I may.”

“That's fine, Tad.” (Tad apparently was Mr. Peabody's first name.) “Mo can stay with me while I finish molting.”

Mr. Peabody receded into the darkness. It was the first time I'd had alone with Helen in a few days.

“I'm sorry Mr. Peabody was a little sharp with you. Sometimes he gets very tense, I don't know why.” Helen walked over to her refrigerator. “Can I offer you something to eat?” Helen asked, pulling out a Tupperware container of beaver carrion.

“I've already eaten, thank you. Helen, I have to tell you again how grateful I am for all you've divulged to me. But again, I have to ask why. Why me?”

“Mo, let's be realistic. I'm over two hundred years old. I'll be lucky if I live another forty. Someone outside the White Houseâsomeone other than Iâneeds to know about the Presidential Pet line. It's the surest way to guarantee its survival. And that's immensely importantâbecause without its survival, we lose an invaluable ingredient of good governance. Presidents need counselâsmart, honest, commonsense counsel. Without this âsacred animal' ingredient, leadership is in a terrible state of imbalance. The executive becomes arrogant, drunk with its own sense of invulnerability. President Eisenhower came to understand this at the end of his presidency when he warned us about the âpotential for the disastrous rise of

misplaced power.

' ”

“I thought he was talking about the military-industrial complex,” I said.

“ âMilitary-industrial complex'? Never heard of it, but I'm sure it's an anagram for something pet-related,” Helen said with a shrug.

“So what do you want me to do with all this?” I asked. “Just carry this with me?”

“I want you to write it down, in a history that once and for all can be read by everyone.”

“You mean no one else has tried?”

“Others have tried,” Helen conceded. “Henry Adams gave it a shot. It was too literary. I considered Edmund Morris but he just kept procrastinating. I thought of Gore Vidal but he's a historical

fiction

writer. You really can't believe anything he writes. So the task now falls to you.”