Amazing True Stories of Execution Blunders (22 page)

On the Friday the Revd Father Ravoux visited the condemned men, finding that little conversation passed between them, though occasionally one would mutter a few words to another in an unintelligible jargon. Most of them lay on the floor in as comfortable a position as their chains would allow, unconcernedly smoking their pipes as if they were engaged in council over some unimportant matter of tribal concern and their lives were not destined to end in three or four short hours’ time.

While the padre was speaking to them, one, Old Tazoo, broke out into a death wail, in which one after the other joined in, until the prison room was filled with a wild, unearthly plaint which was neither of grief or despair, but rather a paroxysm of savage passion. During the lulls in their death-song they would resume their pipes and, with the exception of an occasional mutter or the rattling of their chains, they sat motionless and impassive until one among the elder would break out in the wild wail, when all would join in again, in the solemn preparation for death.’

Following this, the Revd Dr Williamson addressed them in their native tongue, after which they broke out again into their song of death. This was described as:

‘thrilling beyond belief of expression; the trembling voices, their forms shaking with passionate emotion, the half-uttered words through set teeth, all made up a scene which no one who saw it can ever forget. The influence of the wild music of their death-song was almost magical, their whole manner changing after they had closed their singing, and an air of cheerful unconcern marked all of them. As their friends came about them they bade them cheerful farewell and in some cases there would be peals of laughter as they were wished pleasant journeys to the spirit world. They bestowed their pipes upon their favourites and so far as they had any, gave keepsakes to all.

They had evidently taken great pains to make themselves presentable for their last appearance on the stage of life. Most of them had little pocket mirrors, and before they were bound, employed themselves in putting on the finishing touches of paint and arranging their hair according to the Indian mode. Many were painted in war style, with bands and beads and feathers, and were decked as gaily as for a festival.

As those at the head of the procession came out of the basement, we heard a sort of death-wail sounded, which was immediately caught up by all the condemned and was chanted in unison until the foot of the scaffold was reached. At the foot of the steps there was no delay. Captain Redfield mounted the drop, at the head, and the Indians crowded after him as if it were a race to see who would get up first. They actually crowded on each other’s heels and as they got to the top, they took up their positions, forming long rows, without any assistance from those detailed for that purpose. They still kept up a mournful wail and occasionally there would be a piercing scream.

The ropes were soon arranged around their necks, not the least resistance being offered. One or two, feeling the noose uncomfortably tight, attempted to loosen it, and although their hands were tied, they partially succeeded. The movement, however, was noticed by the assistants, and the cords rearranged. The white caps, which had been placed on the top of their heads, were now drawn down over their faces, shutting out forever the light of day from their eyes.

Then ensued a scene that can hardly be described and which can never be forgotten. All joined in shouting and singing, as it appeared to those who were ignorant of the language. The tones seemed somewhat discordant and yet there was harmony to it. Their bodies swayed to and fro and their every limb seemed to be keeping time. The drop trembled and shook as if all were dancing. The most touching scene on the drop were their attempts to grasp each other’s hands, fettered as they were. They were very close to each other and many succeeded. Three or four in a row were hand in hand, swaying up and down with the rise and fall of their voices. One old man reached out each side but could not grasp a hand; his struggles were piteous and affected many onlookers. We were informed by those who understood the language that their singing and dancing was only to sustain each other, that there was nothing defiant in their last moments, and that no death-song, strictly speaking, was ever chanted on the gallows. Each one shouted his own name and called the name of his friend, saying in substance, ‘I’m here! I’m here!’

The traps were held in place by wooden posts placed upright beneath them, and at one tap of the drum, almost drowned by the voices of the Indians, first one, then another of the stays were knocked away by the soldiers, and with a crash, down came the drops. All the Indians were instantly jerked downwards by their own weight; however the rope by which one was suspended broke, and his body came down on the boards with a heavy crash and a thud. There was no struggling by any of the Indians for the space of half a minute; the only movements were the natural vibrations caused by the fall. In the meantime a new rope was placed round the neck of the one who had fallen and, it having been thrown over the beam, he was soon hanging with the others. After the lapse of a minute, several drew up their legs once or twice, and there was some movement of their arms. One Indian, at the expiration of ten minutes, still breathed, but the rope was better adjusted and life was soon extinct.

The bodies were left hanging for about half an hour, the physicians then reporting that life was extinct. Soon after, several United States’ mule teams appeared and the bodies were taken down and dumped into the wagons without much ceremony. They were transported down to the sandbar in front of the city and all buried in the same hole. Everything was conducted in the most orderly and quiet manner. As the wagons bore the bodies of the murderers off to burial, the people quietly dispersed.’

The journalist concluded by saying, ‘It is unnecessary to speak of the awful sight of 38 human beings being suspended in the air. Imagination will readily supply what we refrain from describing.’

It is unlikely that such a horrific scene will ever occur again; as far as is known, it was the greatest number of victims ever to be hanged at the same time.

A ruthless and cold-blooded murderer, John Thurtell was tried and condemned to death in 1824, a penalty which left him so unmoved that on hearing directions being given by a surgeon to the students who would be dissecting him after his execution, he listened unconcernedly and took a pinch of snuff. In the condemned cell he expressed much interest in the possible outcome of a bout of fisticuffs shortly to take place between two famous pugilists, Tom Spring and Langan, at Worcester racecourse. At dawn on the day following the bout, Thurtell, the gallows looming up before him, spoke his last words. ‘Who won the big fight, I wonder?’ he asked.

Elizabeth and Josiah Potts

Too long a drop decapitated, too short a drop strangled; although the former must have been the more horrendous spectacle for witnesses, it probably brought a quicker, more merciful death to the victim, and in 1890 in Nevada a story of both errors unfolded, the victims being Josiah Potts and his wife Elizabeth.

They had both been found guilty of murder; on the scaffold they embraced and declared their love for each other before the sheriff operated the drop, sending both plunging into the waiting pit. It was then that disaster struck. The noose tightened around Josiah’s throat, death taking seemingly aeons of time; it was reported that he lived for a further fifteen minutes. However, Elizabeth was a large lady and while the length of drop brought a slow death to her husband, her weight imposed such a strain on a rope of the same length that the noose severed her windpipe, an artery and the fleshy parts of her throat, blood thereby gushing copiously over her clothes. But she did at least suffer for a shorter time than did her husband.

American Arthur Gooch, a habitual criminal, broke out of jail and in an ensuing gun battle, shot and injured a police officer. He was captured, tried and sentenced to death. Due to be hanged at midnight on 19 June 1936, he had previously persuaded the prison warden to obtain a radio for him so that he could listen to the world heavyweight championship fight between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling, scheduled for that evening, a Thursday. However, the fight was postponed for twenty-four hours, Gooch commenting dryly, ‘Won’t need a radio if it’s going to be Friday night – I’ll be up there somewhere; think I’ll float over and grab myself a seat right above the ring!’

Dr William Pritchard

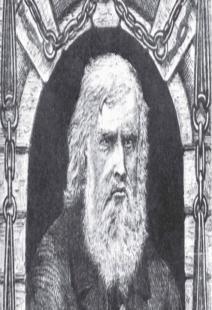

William Calcraft

The hangman William Calcraft was essentially a family man; he bred rabbits, kept a pony, grew flowers and loved fishing. He had only one failing: he rarely, if ever, gave his client a drop of more than three feet, if that; consequently most of them were throttled to death. At that time, such a method was standard practice; no one ever considered that there could be, or should be, a more humane alternative; the criminal deserved their punishment, and anyway, a speedy, merciful method of hanging would reduce entertainment time for the good folk clustered round the scaffold to a mere minute or two – and that would never do! One who stayed suspended on the end of Calcraft’s rope for an unconscionable length of time was Dr William Pritchard.

A medical practitioner in Glasgow, Dr Pritchard was somewhat of a fantasist, constantly boasting of his close friendship with foreign statesmen whom he had never met and giving lectures about countries he had never visited. Such mild eccentricities could easily be overlooked by Victorian society; what could definitely not be ignored were the suspicious deaths, first of his mother-in-law, Mrs Jane Taylor, and later of his wife, Mary Jane (Minnie), whom he had married fifteen years earlier. Regrettably, suspicions initiated by an anonymous letter were confirmed, post-mortems revealing that they had both been poisoned by eating some tapioca pudding which contained opium, antimony and aconite.

At his trial for murder in 1865 the accused man tried to blame one of the housemaids, a young girl named Mary M’Leod whom, he averred, had been his mistress (she had earlier become pregnant by him and he had employed his medical skills in carrying out an abortion), and he accused her of murdering his wife so that he could marry her. The maid, while agreeing that she had been his mistress, tearfully declared that he had indeed promised to marry her if his wife should die, but that she had played no part in the crimes. Even if she had, her defence pointed out, why should she have also killed her employer’s mother-in-law? And when the jury heard a local chemist testify that the prisoner had frequently purchased antimony from his pharmacy, and that Mrs Pritchard would inherit a large sum of money in the event of her mother’s death, the fact that the older lady had died first left them in no doubt as to Pritchard’s culpability. They brought in a verdict of guilty, and the judge wasted little time in pronouncing the death sentence.

The date of the execution happened to coincide with the annual Glasgow Fair, a gala which always attracted a multitude of visitors, and the council had to arrange for the removal of some of the roundabouts and sideshows in order to accommodate what was definitely not a sideshow, the scaffold itself, around which, as the time drew near, more than 100,000 spectators thronged, order being maintained by some 750 police constables.

Understandably the case and the verdict produced a furore in Scotland, the newspapers of the day selling a record number of copies, all devoting page after page to the poisoner’s and his family’s background, their way of life and his way of death. The

Edinburgh Scotsman

gave a ‘fly-on-the-wall’ account of the day’s proceedings:

‘the prisoner retired to bed a little before midnight on his last night, and although he was somewhat restless at first he soon fell into a deep sleep and slept soundly until five o’clock in the morning. When he rose he seemed to be perfectly calm and gave his attendants the impression that he was more lively and cheerful than he had been since his removal to Glasgow. He partook of some coffee and bread that had been provided for him and appeared quite prepared for the dreadful ordeal which he was to go through.

His appearance on the scaffold was the signal for a deep howl of execration from the immense crowd. Among those present were a number of modellers from Edinburgh who had received the sanction of the authorities to take a cast of the culprit’s head after execution to enrich the collection of similar curiosities in the museum of the Phrenological Society. Calcraft, the executioner, stepped on to the scaffold along with the doomed man and was received with a few groans and hisses. Quietly, and with an expertness that showed him to be well accustomed to his awful work, the executioner stationed his victim above the drop and busied himself in the grim work of his office. The white cap was expeditiously drawn over the head of the culprit and the fatal noose adjusted about his neck. The prominent figure of the executioner, his head covered by a black skull cap and his long white beard lending to his aspect a sort of venerable air, strongly attracted the attention of the crowd and drew forth repeated sounds of recognition.