An Evening with Johnners (13 page)

Read An Evening with Johnners Online

Authors: Brian Johnston

A

nd the other one was also in the same year, just before that, in 1963 at that wonderful match against the West Indies at Lord’s. Do you remember? Colin came in at number eleven, his wrist in plaster, two balls to go and six runs to win, and with David Allen at the other end. It was a draw, but it was a great match.

Before it started, Jim and I were doing the television and we were told, ‘There’s ten thousand people in St

Peter’s Square, waiting for that white puff of smoke to come out of the Vatican chimney and announce that a new Pope has been elected. If this happens during the Test, we’ll leave it immediately and go over to our man in Rome, who’ll tell us who the new Pope is.’

So we were waiting for this call to Rome, yapping away, doing the commentary, when out of the corner of my eye I saw that the chimney on the Old Tavern had caught fire. Black smoke was belching out, so we got the cameras on to it and I said, ‘There you are. Jim Swanton’s been elected Pope!’

He was delighted.

T

hen there was dear old John Arlott, who died over a year ago now. Very sad. To me, John Arlott did more to spread the gospel of cricket than anybody. That

marvellous

Hampshire burr with the slightly gravel voice,

especially

in the years after the war, went all around the world, from igloos in Iceland to the outback in Australia.

Every time I heard him, you could smell bat oil and new-mown grass, and picture white flannels on a village green with a pub and a church. He could really conjure up cricket for you, and he was very good at painting a picture with words, because before he became a

commentator

, he was a poet.

To show you how quick he was, and witty, and how well he did it – there was a chap called Asif Masood, who bowled for Pakistan in 1962. Bill Frindall says I once called him Massif Ahsood. (I don’t think I did, but never mind!) This chap ran up with bent knees, very low down, and the first time John saw him, he said, ‘Reminds me of Groucho Marx chasing a pretty waitress!’

John was unique and we miss him terribly. He retired in 1980 and did his last broadcast during the Centenary Test. We knew that he was due to finish at exactly ten to three, and the cameras were there taking pictures of him, and we all thought he’d do a tremendous

peroration

, saying, ‘Thank you for all the years you’ve listened to me.’

But he got to the end of his over, and when it was time to hand over he said, ‘After a word from you, Trevor, it’ll be Christopher Martin-Jenkins.’

No more. He got up, walked out and disappeared into the pavilion. Luckily Alan Curtis, on the public address, had heard the broadcast and announced to the crowd: ‘John Arlott has just done his last broadcast.’

The Australians were fielding and they all applauded; the crowd stood up and applauded; and Geoff Boycott, who was batting, took his gloves off and clapped! But the interesting thing is that John only came back for one morning of a Test match in all that time afterwards, to open a stand for Neville Cardus. He didn’t ever come back. He stayed down in Alderney, where he wrote books on wine but wasn’t very well, sadly, for the last few years. But miss him? Of course we do. He was unique and there will never be another.

W

e’ve got one or two eccentric people in the box. What about Blowers – ‘my dear old thing’ – Henry Blofeld? Well, when he was aged eighteen, Henry was one of the best wicket-keepers at Eton anyone had ever seen. He was brilliant. He was captain of Eton, and one day he rode a bicycle out of the playing fields at Agar’s Plough into Datchet Lane and was knocked over by a Women’s Institute bus.

He was lying there in the road, the ambulance took him away and he had an operation on his brain. He got a Blue at Cambridge after that! So he was all right, but I think that accident gave him what I call ‘busitis’, because doing a commentary at Lord’s, he’ll say, ‘That ball goes through to the wicket-keeper. I can see a number eighty-two

bus approaching … a Green Line bus … a

double-decker

bus …’ He has buses on the brain! At the Oval once, he said, ‘I can see a good-looking bus!’

At Headingley, he said, ‘I can see a butterfly walking across the pitch … and what’s more, it’s got a limp!’

If a pigeon flies by, it’s ‘a thoughtful-looking pigeon’, and he always gets terribly excited. Someone dropped an easy catch and he said, ‘A very easy catch. Very easy catch. It’s a catch he’d have caught ninety-nine times out of a thousand!’

There’s Don Mosey, ‘The Alderman’. He was talking about David Gower’s one hundredth Test match at

Headingley

in 1989 and he said, ‘This is David Gower’s one hundredth Test match and I’ll tell you something. He’s reached his one hundredth Test in fewer Test matches than any other player!’

T

hen we have ‘The Bearded Wonder’, Bill Frindall, the statistician who does all our work for us. He gets up at half past five every morning and enters into his books every single score made the day before, including

telegrams

that have come in from overseas. He’s got details of every single innings played by any first-class batsman. It’s a marvellous record, in all these books, so we don’t have to do too much homework.

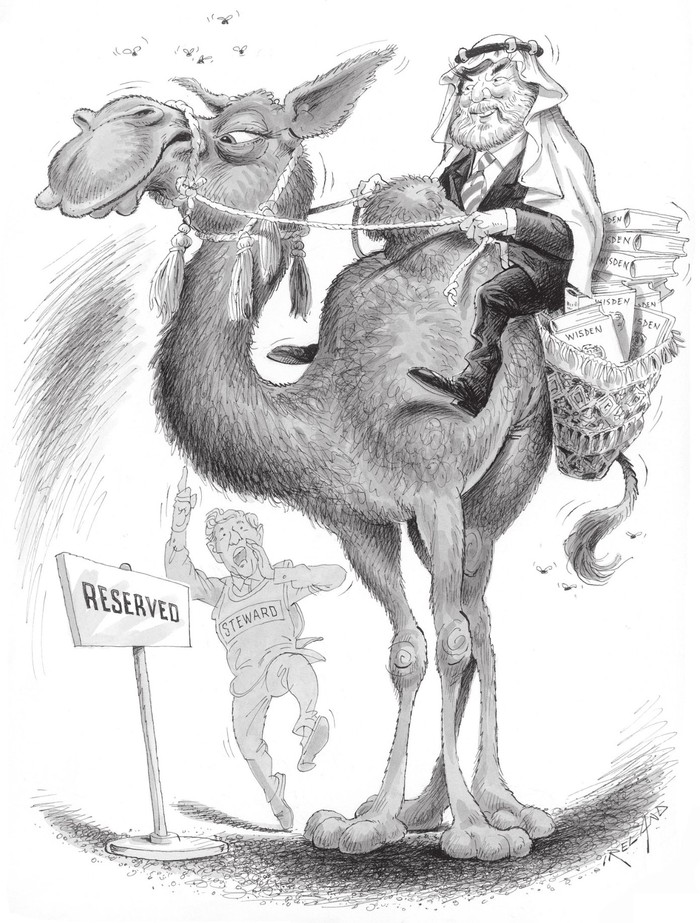

About eight years ago, during The Oval Test, there was a cocktail party to which he was invited, and he went. There was an Arab prince there, in full regalia with the head-dress and white robes, and this Arab prince said to Bill, ‘I’ll give you fifty quid for your favourite charity, if you dress in my clothes tomorrow and score all day in the commentary box.’

So Bill agreed and the prince went off, changed into a suit and gave Bill the clothes. Next morning, Bill put them on and drove up to the Hobbs Gates at The Oval. On the front of his windscreen it said ‘BBC Radio’, and they looked at it and thought, Hmmm. Arab? New commentator? Johnston’s got the sack, good! and they let him in.

At The Oval, there is a special space reserved by the back door of the Pavilion, where Bill is allowed to park his car, because he has all these books he has to carry. It is always kept sacred for him. So he drove round as usual, dressed as the Arab, and the steward, seeing an Arab coming into this sacred space, said, ‘Sorry, sir. Do you mind backing out? Only Mr Frindall can park here. Do you mind backing out, please sir …’

Bill Frindall unwound his window, stuck his Arab’s head out and said, ‘I’ve just bought The Oval. I shall park where I bloody well like!’

I

wish I could tell you all Fred’s one liners, but they’re not quite suitable. I think I can risk this one because it’s very funny. About a year ago he said, ‘Johnners? Hear about the flasher who was about to retire?’

I said, ‘No, Fred, I haven’t.’

‘Oh,’ he said, ‘he’s decided to stick it out for another year!’

He told me a clean one last year. ‘Johnners,’ he said, ‘hear about the Pole who went to have his eyes tested? The oculist said, “Can you read that bottom line on the chart?” The Pole said, “Read it? He’s my best friend!”’

T

here are so many stories about Fred, but one which Norman Yardley assured me was true happened in about 1949, when Fred was eighteen or so. Yorkshire used to play matches against various clubs to get fit for the cricket season. Nowadays, people run ten times round the ground or do press-ups, but in those days they used to play cricket to get fit for cricket, which was good.

They were playing the Yorkshire Gentlemen at Escrick and Fred, very young, virile and tough, bowled very fast bouncers at these poor Yorkshire Gentlemen. Four of them were carried off and went to hospital. They were about twenty-six for six, when out of the pavilion came a figure with grey hair, white bristling moustache, I

Zingari cap with a button, and a silk shirt buttoned up at the sleeves.

Norman went up to Fred and said, ‘Look, this is

Brigadier

So-and-So, patron of the club. Treat him gently, Fred.’ So Fred, who was a very generous man, went up and approached this apprehensive-looking Brigadier and, with a lovely smile, said, ‘Don’t worry, Brigadier. Don’t worry. I’ll give you one to get off the mark.’