An Evening with Johnners (3 page)

Read An Evening with Johnners Online

Authors: Brian Johnston

N

ow the theme of this evening is really to let you know how lucky I have been in life and how much fun I have had. I started off by having a wonderful family: a mother and father, a sister, two brothers – a very close family.

My wife has put up with me for forty-five years, which is very sweet of her, and we have five lovely children, and they have produced seven [now eight] grandchildren. And it is, quite seriously, very important if you are doing a job like mine, rushing around and meeting a lot of people, to come back to a home in which you know there is love and happiness and comfort. So that’s my luck Number One.

I

got lucky in my education, because I was sent to the oldest preparatory school in England. The food matched the age of the school! It was in Eastbourne, Temple Grove it was called, and I only remember two things about it really. The matron had a club foot, which was unusual, but the headmaster had a glass eye. It was a very well disguised glass eye and I said to someone, ‘How do you know it’s a glass eye?’

‘Oh,’ he said, ‘it came out in the conversation.’

I then went to Eton and again I am lucky, because it’s the best trade union in Great Britain. There are so many Old Etonians around the place; you meet them and it helps and I have lots of happy memories there.

My late friend, William Douglas Home, the playwright, did something which amused me. He was sitting an exam and they brought the questions to his desk and one of them was: ‘Write as briefly as you can on the future of one of the following subjects.’ The first was socialism and the second was coal. So he thought for a moment and chose coal. He wrote one word: ‘Smoke’.

And he got seven out of ten, which wasn’t bad!

We used to go to a housemaster’s house for our history lesson and if the telephone rang in his study he would say to one of us, ‘Go and answer the telephone.’ At the time he was very keen on the film actress Anna May Wong. She used to come and have dinner with him and he rather fancied her.

One day the telephone went and he said to this chap, ‘Gilliat, go and answer the telephone.’

Obviously he hoped it was Anna May Wong and when Gilliat came back two minutes later the master said, ‘Yes, yes, who was it?’

‘Sorry, sir,’ said Gilliat, ‘Wong number!’

T

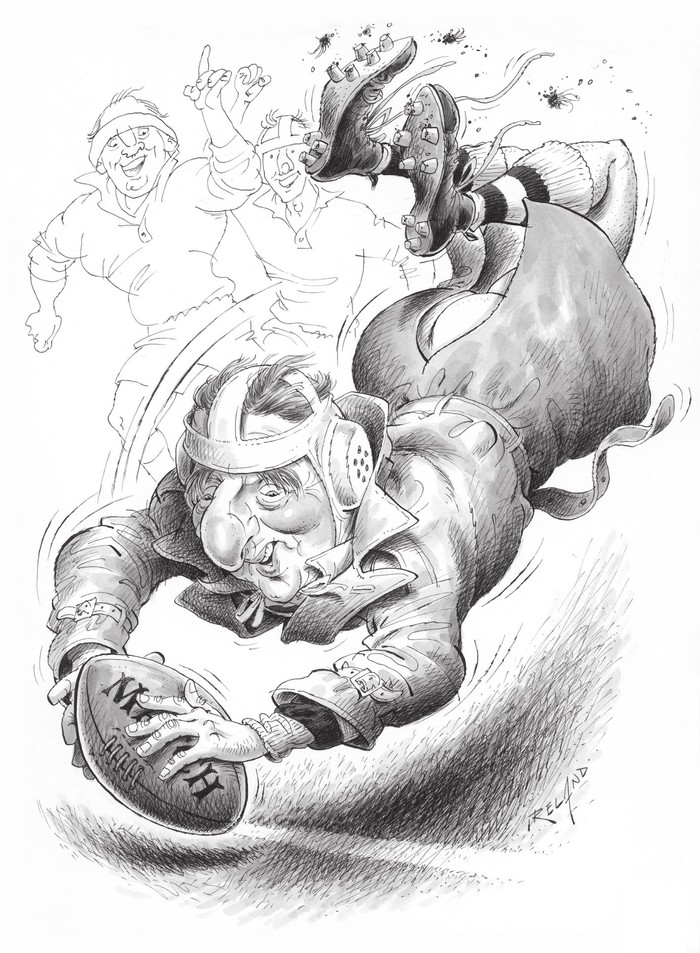

hat was Eton. Then I went to Oxford, where I read history and P. G. Wodehouse and played cricket about six times a week, which was good fun. And I only achieved one thing there which I don’t think anybody else has ever achieved. I actually scored a try at rugby wearing a macintosh. I’ll tell you how it happened.

I was playing for New College against Trinity and someone tackled me and pulled my shorts off. I went and stood on the touchline while they went to get another pair and someone said, ‘You’d better put this macintosh on to cover your confusion,’ which I did.

The ball came down the line and when it got to me on the left-wing I said, ‘Outside you!’ and took the ball. The referee should have blown his whistle because I hadn’t got leave to go back on, but he was laughing so much that he just went

pffftt

and couldn’t blow and I touched down between the posts!

T

hen, like so many people of that age, I wasn’t sure what career I wanted to follow. So I was lucky, in a way, because we had a family business. We used to export coffee from Brazil. We had an office in London and so, reluctantly, I went in there. I didn’t understand a thing about coffee. I can confirm there are an awful lot of coffee beans in Brazil but that’s about all I can tell you.

I don’t think the manager took to me very well. He thought he’d got me one day. I’d had a late night and arrived about ten o’clock and he summoned me to his office.

‘Johnston,’ he said, ‘you should have been here at nine thirty.’

‘Why, sir,’ I replied, ‘what happened?’

And he didn’t like that a bit. So it was a good thing for me when the war came and I was able to say to them, ‘Sorry, I won’t be coming back.’

A

gain, I was lucky, because just before the war began, in about March 1939, some friends and I decided that war was obviously going to come, so we ought to try and get into a good regiment.

By a little bit of luck, and the fact that a cousin of mine was commanding the 2nd Battalion at Wellington Barracks, I got in what obviously I think is the best regiment in the British Army – the Grenadier Guards. We had to train every evening. We used to go from the City in our bowler hats and pinstripe suits and march up and down throughout that hot summer, until in the end they said we were qualified to be officer cadets.

When the war came in September this meant we could go straight to Sandhurst to learn how to become officers.

I can never resist making a bad joke, as you probably

know, and I tried one out in the first fortnight I was there. They used to have a thing called TEWTS: Tactical Exercise Without Troops, where they took twenty of you out and gave you various military problems to solve.

The officer took us up on a high ridge and said to me, ‘Johnston, you’re in charge of a section on the top of this ridge and approaching a hundred yards away are a squadron of German Tiger tanks. What steps do you take?’

‘Bloody long ones, sir,’ I said.

He didn’t think that was very funny. I was ‘put in the book’ for it and had to do a couple of drills, but in the end I passed out from there and got into the Grenadier Guards.

Now when you join the Brigade of Guards it is very strange. You go into the mess and they cut you dead for a fortnight. You probably know half of them, so you try and talk with them but no, they turn away. This is evidently to make sure that new boys don’t get too swollen headed.

After a fortnight is up, they more or less look at their watches and say, ‘Hello, Brian. Are you here? Have a drink!’ and it is all very matey. A bit stupid, I thought, and it happened to me at Shaftesbury when I joined up in 1940.

But at the same time a friend of mine was joining up down in Sherborne with the Hampshire Regiment and his Commanding Officer treated him completely differently.

‘Very glad to have you with us. Want you to get to

know people. Want people to get to know you. Monday night we’ll have a thrash in the mess. Lots to drink, never did anybody any harm.’

My friend said, ‘Terribly sorry, sir, don’t drink.’

‘Don’t worry about that then,’ said the Commanding Officer. ‘On Wednesday night we’ll get a few girls up from the

NAAFI

and have a bit of slap and tickle in the mess. Great fun. You’ll enjoy it.’

My friend said, ‘Terribly sorry, sir, I don’t approve of that sort of thing.’

So the Commanding Officer looked at him for a moment and said, ‘Excuse me for asking, but you aren’t by any chance a queer?’

‘Certainly not,’ said my friend.

‘Pity,’ said the CO, ‘then you won’t enjoy Saturday night either!’

S

o I actually had a very good war with the Grenadiers, and I only mention them, really, because it is thanks to them (or not) you have had to listen to me, if any of you have, since I joined the BBC in 1946. When we were waiting to go to Normandy, two well-known commentators from the BBC, Wynford Vaughan-Thomas and Stewart MacPherson, came to brush up on their war reporting, so I got to know them, which was a bit of luck.

I got out of the army in 1945. I went to a party and I happened to run into them again. Another bit of luck. They said, ‘We’re very short of people at the BBC because they’re still in the services. We want someone in Outside Broadcasts, we know you can talk a bit, come and have a test.’ I said, ‘I don’t want to join the BBC,’ but they said ‘Come on!’ so I said, ‘All right,’ because I had nothing else to do.

They set me up in Oxford Street, gave me a microphone and said, ‘Ask passers-by what they think of the butter ration.’ Well, if you ask silly questions, you get silly answers, but what they said was, ‘It wasn’t very good but at least you kept talking. Come and join us for a bit.’

So I said, ‘I will, but I shan’t stay long.’ That was in January 1946 and funnily enough I was with them until I retired as a member of staff in September 1972, so it suited me, if not everybody who has had to listen to me.