An Evening with Johnners (5 page)

Read An Evening with Johnners Online

Authors: Brian Johnston

T

o let you know what sort of thing goes through a commentator’s mind, we have an expression we use when describing processions and I had to say to myself, when the cortège came past me,

not

to use it. The expression is: ‘Here comes the main body of the procession.’

If I had said it then I should probably have got the sack. But those things do go through one’s mind.

T

he other difference between radio and television is in interviewing. Now, if I am doing a three-minute interview with someone on radio, I’ll have a stopwatch. When we get to about two and three-quarter minutes I’ll show him the watch, dig him in the ribs or kick him in the shins, and hopefully he’ll finish and I can hand back to the studio.

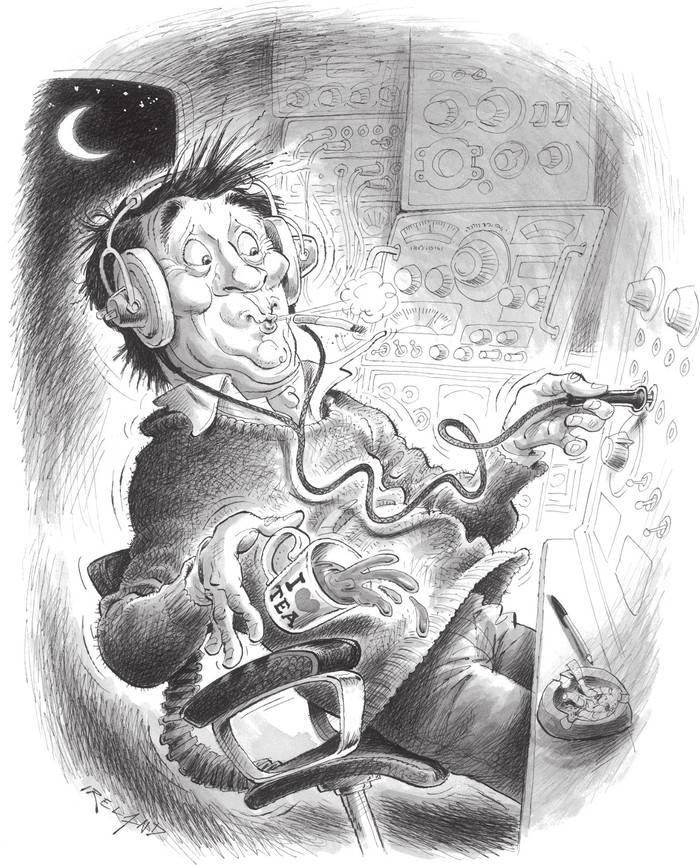

But in television it’s very different. If I’m interviewing someone up here, say, for television, the camera will probably be down in the second row and alongside it will be a chap called a studio manager who has headphones on, linked to one of those huge command vehicles. That’s where the producer sits and gives his instructions.

He says, ‘Right, tell Brian to go ahead,’ and you get a signal to start and begin the interview. Then, when he wants you to finish, he gives you a wind-up sign, or if he wants you to go a little longer he signals you to stretch it out a bit. If you overrun, he goes

qweeck

with his finger across his throat, meaning, ‘Cut!’

B

ut it doesn’t always work. I was doing a programme from an exhibition in the Horticultural Hall and on one of the stands was a jet engine. It was my job to interview a very well-known scientist called Sir Ben Lock-Spicer and in three minutes he had to describe basic things about the jet engine such as what goes in the front and what goes out behind. We rehearsed him and he did it very well indeed.

When they handed over to ‘Brian Johnston’, I got the signal to go ahead and I said, ‘Yes, we’ve got Sir Ben Lock-Spicer to tell us all about the jet engine,’ and he did it absolutely right. When he had finished, as we’d rehearsed, the chap was winding me up very confidently and I said, ‘Well, thank you very much to Sir Ben, that was very interesting.’

‘Oh,’ he said, ‘this is

far

more interesting,’ and went up to the other end of the engine. The studio manager was now going

qweeck

, making cutting signs, so I waited

for Sir Ben to draw breath and said, ‘Well, thank you very much, Sir Ben, we’ve learnt an awful lot.’

‘Oh,’ he said, ‘you haven’t learnt half of it yet,’ and went up the other end! The chap was going crazy, going

qweeck, qweeck, qweeeck,

and we overran. So it doesn’t always work. Nowadays they don’t worry. They say, ‘Sorry, time’s up,’ and cut someone off in mid-sentence. In those days we tried to be polite.

A

nother thing is, if you’re interviewing someone and they say something that isn’t meant to be funny, at least on the radio you can hide your smile and hopefully suppress your giggles. But on television, if someone says something funny and it’s not meant to be, you mustn’t be seen to smile.

In 1952, when the Indians were here, I was down at Worcester. We always did the first match of the tour on television and inevitably it was raining, as it always did. About lunchtime my producer said, ‘Right, go out under an umbrella and interview the Indian manager. We’ll try and fill in some time.’

The Indian manager was a little man called Mr Gupta, a bit of a volatile chap. I don’t know how much English he understood. Anyhow, I got him under the umbrella and said, ‘Mr Gupta, have you got a good team?’

‘Oh yes, we’ve got a very good team.’

‘Really,’ I said. ‘Any good batsmen?’

‘Seven very good batsmen.’

‘What about the bowlers?’

‘Six very good bowlers.’

I thought this was getting a bit boring and I’d better try another tack, so I said, ‘What about yourself. Are you a selector?’

‘No,’ he replied, ‘I’m a Christian!’

So I pretended not to laugh and said, ‘So, tell me about your wicket-keeper …’

B

ut I

was

meant to laugh on the occasion when I interviewed Uffa Fox at the Boat Show. Do you remember Uffa Fox? He was the great yachtsman who taught Prince Philip how to sail, a great old sea salt. Sometime before, he’d married a French lady. Nothing very odd about that, except that she couldn’t speak a word of English and he couldn’t speak a word of French.

So when I was interviewing him at the Boat Show I said, ‘Before we talk about the boats, excuse me asking a rather personal question. You married this lady, who doesn’t speak your language and you don’t speak hers. How does a marriage like that work?’

‘Oh,’ he said, ‘it’s quite easy, my dear chap. There are only three things in life worth doing. Eating, drinking and making love – and if you talk during any of them, you are wasting your time!’

A lovely bit of philosophy, isn’t it?

N

ow things often go wrong. Sometimes you know they do, sometimes you don’t. I’ll give you two instances which luckily you didn’t know about.

In the late forties and fifties we used to go live in the evenings at about eleven o’clock at night to a wood at Hever Castle in Kent. We used to broadcast the birds singing. If it wasn’t raining, the nightingales would sing and so would the other birds.

I used to do this with Henry Douglas-Home, Lord Home’s younger brother, who was known as ‘The Bird Man’. We would run microphone leads from a van to various parts of the wood and one night at about ten o’clock (remember we were on live at eleven o’clock) he said, ‘We’ve just got time to check the microphones.’

So he asked the engineer, ‘Will you bring up the one by the bluebell glade,’ and the engineer turned it up and there was a willow warbler, or some other bird.

‘Right,’ he said, ‘that’s working. Now, the one by the little bridge by the stream,’ and he brought that up and there was a wood pigeon. Then he tried the one by the fir tree and there was a cock pheasant.

Finally he said, ‘We’ve just got time. Let’s check up on the one over the rhododendron bush, where we’ve got the nightingale.’

The engineer brought the microphone up and we heard a girl’s voice say, ‘If you do that again, Bert, I’ll give you a slap in the kisser!’

He just had time to run round and say, ‘Please come out.’ And a very disgruntled couple came out, doing various things up and saying, ‘You might have let us make love in peace.’

He pointed out that in about five minutes time we’d have said, ‘Let’s hear the dulcet tones of the nightingale,’ and goodness knows how far they’d have got by then!

T

here was another occasion when it was lucky we weren’t on the air. I used to do these things in

In Town Tonight

for about three or four minutes each week where I’d do something live and exciting. One of the things we

thought we’d do was see what it was like lying under a train. We found out from Southern Region that, if ever you go into Victoria, about a mile outside the station there are some planks between the lines. If you take up the planks, there’s a well about three feet deep where the workmen can crouch.

They said I could go in there with my microphone and one of their men and they’d try to get me the

Golden Arrow.

So there I was, and when the studio said, ‘Where are you this Saturday night, Brian?’ I said, ‘I’m lying between the lines outside Victoria Station. We were going to get the

Golden Arrow

but I’ve just heard that it’s late and we’ve got an electric train instead.’