Anatomy of Fear (38 page)

The young black cop said, “Our orders were to check out the premises, not to—”

I’d already drawn my gun and pushed the door open, so he didn’t finish, just got his revolver out while his partner did the same.

I led them into the apartment, holding my breath. I called out,

“Uela!”

There was no answer.

The big redhead cop spied the Eleggua by the door. “What’s with the voodoo shit?”

I almost punched him.

Terri told him to go canvass the rest of the building, probably just to get him out of my face. Then we started down the narrow hallway I’d known all my life.

“Stay here,” she said to the black cop. “And watch our backs.”

He flinched. “You think the perp’s still here?”

Terri didn’t answer him and I had no idea, my usual radar buried under anxiety.

We checked everything. The front-hall closet was crowded with coats and scarves, impossible to hide in; the living room wide open; the

cuarto de los santos

produced raised brows from Terri, but she didn’t say anything, and it was empty; so was the bathroom.

“Looks clean,” she said. “Can you try calling her again?”

“This is her only phone.”

“No cell?”

“My grandmother? You kidding? She hasn’t even graduated to a cordless.”

We went back to the kitchen, and I spread the drawing that I’d taken from Wright’s trash onto the table.

“Did I read this wrong?”

The young uniform leaned over my shoulder. “What is it?”

“A drawing of this building, can’t you see that?” I had no patience. All I could think was that Tim Wright had been here and taken my grandmother with him. But where?

“Looks it,” he said. “But the number’s wrong.”

“What?” The guy was really working my nerves.

“This isn’t 106. It’s 301, according to the address we got on our orders—and that’s what it says outside.”

Jesus, he was right. I hadn’t noticed until he said it. The minute I’d seen the sketch and recognized it as my grandmother’s building, I’d just reacted. Now I looked at the three sketches we’d taken from Wright’s work table and tried to see if I’d missed anything else.

The cop Terri had sent out to canvass the building came back breathing heavy. “Fuckin’ elevator is out.”

“What about the neighbors?” she asked. “They see—hear—anything?”

“Place is practically deserted. Maybe ’cause it’s Sunday,” he said, “And because of the holiday.”

“What holiday?” I asked.

“It ain’t a biggie—unless you ask my wife, Maureen—Feast of the Annunciation. She’s like an expert on everything Catholic. I don’t know what it’s about, the feast, I mean, but Mo, she doesn’t miss a single—”

I stopped listening. “One-oh-six,” I said aloud. Then it clicked, and I saw it: what Wright was planning to do. “Jesus Christ!”

“Yeah,” said the redheaded cop. “I guess he had something to do with the feast.”

I heard my grandmother’s words when I’d kissed her good-bye.

Change my clothes and go to church.

“A church!” I shouted, already moving, halfway out the door. “That’s where Wright’s headed. One-oh-six is 106th Street. My grandmother’s church. Saint Cecilia’s.”

T

erri was calling for more backup as I sped the Mercedes through the streets of Spanish Harlem. I’d told her what I thought was about to go down.

“You’re sure about this?” she asked. “I just want to make sure before I call out the cavalry.”

I nodded, eyes on the road, mind focused on getting there. “Yes,” I said. I couldn’t be certain, but that’s what his drawings were telling me. I felt like I knew this guy—the way he thought, what made him tick. “He’s been practicing, right? We saw that in his sketches. Three, four pictures of each vic till he gets it right. Maybe they were all practice—the murders, I mean, to build up his courage for something bigger, for

this.

” My mind was flooding with images—going to the church with my grandmother; there with Julio as a kid, the two of us helping to paint a funky replica of the

Last Supper

in a small basement room; Wright’s explosion sketches—past and present, bodegas and

botánicas

blurring past the car windows.

Terri was still on her cell when I made the turn onto 106th Street, tires screeching.

“There it is,” I said. “Santa Cecilia.”

I

nside, the church was about half full. Not quite the standing-room-only Wright had probably expected and wanted, but enough to make a statement.

The priest was reading, switching between Spanish and English. Behind him a huge crucifix, garishly colored; Christ’s flesh, pale yellow, striped with intense vermilion blood. Dozens of candles were burning and I could smell incense in the air. It brought to mind Maria Guerrero’s

bótanica

on a grander scale.

I scanned the room, but couldn’t find my grandmother. “I don’t see her,” I said, my panic escalating.

“We’ll find her if she’s here,” said Terri.

And what if she wasn’t? What then? I was no longer sure. Suppose Wright had made that drawing with the wrong number just to throw me off.

I started down the aisle looking for familiar faces, whispering the same question: “

¿Has visto á Dolores Rodriguez?”

I tried hard to keep the anxiety out of my voice. I didn’t want to start a panic.

No one seemed to have seen her, a few people voicing objection to my disturbance.

“¡Silencio! ¡Silencio!”

A friend of hers worked her way out of a pew. She said my grandmother had promised to meet her at church, but had never shown up.

The priest stopped the service and the congregation went silent, everyone staring at me and Terri. I didn’t care. I got up on the altar and asked him if he’d seen my grandmother. He said no, told me I had to go, that I was ruining the service. I leaned toward him, and whispered, “You have to get everyone out of here.”

He looked at me as if I were crazy.

“¿Por qué?”

The congregation was getting agitated, whispers swelling, a few people muttering, pointing at me.

The priest took hold of my shoulders, and said,

“Debes ir,”

that I should go.

I heard the distant whine of sirens.

“Backup is arriving,” said Terri. “I have to go out and meet them.” She turned to the priest and spoke very calmly. “In a few minutes there are going to be a lot of police here. I need you to ask your parishioners to leave. Do you understand?”

His face was filled with questions.

“Listen to her!

¡Escúchala!

” I said.

There were doors on either side of the altar that led to the sacristy. I chose the one closest to me.

B

y the time Terri got outside, the scene had taken on movielike proportions: a caravan of cop cars, EMT, ambulances, sirens blaring, beacons flashing; behind them the Bomb Squad, two vans with a SWAT team; two of her own men, O’Connell and Perez; detectives and uniforms emptying out of cars, heading her way.

She was going to have to handle this. It was her case until the feds got here. She still had no idea if Wright was inside. If he wasn’t, she had just cost the NYPD a lot of money—and plenty of embarrassment. There was a TV news crew setting up across the street.

The local precinct captain reached her first, heavyset guy, face red, breathing heavily. “What’s going on?”

“First off,” she said, “get your men to cordon off the street—and get these people back.” She gestured at the locals who were crowding the sidewalk in front of the church. “And see what you can do to shut down that damn news van.”

The captain went into action and Terri felt the rush that accom

panied power. She made her way to the SWAT team leader, a guy who looked like he’d stayed too long at the gym, overmuscled arms unable to lie flat against his sides. Behind him, his men were suiting up and Terri knew the sight of a dozen men carrying Mac-10 rifles would scare anyone. “I don’t want a panic,” she said. “But we have to get everyone out of the church. Give it a few minutes. The priest is asking everyone to leave quietly, and hopefully they will.”

I

heard the sirens. If Wright was in the church, he could hear them too.

My pulse was racing, blood pounding in my ears, but I had to stay calm, had to think. Where would he go if he wanted to be concealed and still do the most damage?

The basement.

The verbal part of my brain shut down and I was all visual instinct.

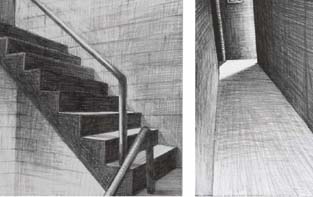

I saw a staircase and took it.