Annapurna (17 page)

Authors: Maurice Herzog

‘There’s not a shadow of doubt; we ought to be able to get up Annapurna.’

9

Annapurna

AN ASTONISHING SIGHT

greeted me next morning. Lachenal and Rébuffat were sitting outside on a dry rock, with their eyes riveted on Annapurna. A sudden exclamation brought me out of my tent: ‘I’ve found the route!’ shouted Lachenal. I went up to them, blinking in the glare. For the first time Annapurna was revealing its secrets. The huge north face with all its rivers of ice shone and sparkled in the light. Never had I seen a mountain so impressive in all its proportions. It was a world both dazzling and menacing, and the eye was lost in its immensities. But for once we were not being confronted with vertical walls, jagged ridges and hanging glaciers which put an end to all thoughts of climbing.

‘You see,’ explained Lachenal, ‘the problem … is to get to that sickle-shaped glacier high up on the mountain. To reach the foot of it without danger of avalanches, we’ll have to go up well over on the left.’

1

‘But how the hell would you get to the foot of your route?’ interrupted Rébuffat. ‘On the other side of the plateau that we’re on there’s a glacier which is a mass of crevasses and quite impossible to cross.’

‘Look …’

We looked hard. But I am bound to admit I felt almost incapable of following Lachenal’s explanations. I was carried away on a wave of enthusiasm, for at last our mountain was there before our eyes.

This May the twenty-third was surely the Expedition’s greatest day so far!

‘But look,’ insisted Lachenal, his knitted cap all askew, ‘we can avoid the crevassed section by skirting round to the left. After that we’ll only have to climb the icefalls opposite, and then make gradually over to the right towards the Sickle.’

The sound of an ice-axe distracted our attention for a moment; it was Ajeeba breaking up ice to melt into water.

‘Your route isn’t direct enough, Biscante,’ I told him. ‘We’d be certain to sink up to our waists in the snow: the route must be the shortest possible, direct to the summit.’

‘And what about avalanches?’ asked Rébuffat.

‘You run a risk from them on the right as well as on the left. So you may as well choose the shortest way.’

‘And there’s the couloir too,’ retorted Lachenal.

‘If we cross it high enough up, the danger won’t be very great. Anyway, look at the avalanche tracks over on the left on your route.’

‘There’s something in that,’ admitted Lachenal.

‘So why not go straight up in line with the summit, skirt round the seracs and crevasses, slant over to the left to reach the Sickle, and from there go straight up to the top?’

Rébuffat struck me as being not very optimistic. Standing there, in the old close-fitting jersey that he always wore on his Alpine climbs, he seemed more than ever to deserve the name the Sherpas had given him of Lamba Sahib, or ‘long man’.

‘But,’ went on Lachenal, ‘we could go straight up under the ice cliff and then traverse left and reach the same spot …’

‘By cutting across to the left it’s certainly more direct.’

‘That should be quite feasible,’ agreed Lachenal, letting himself be won over.

Rébuffat’s resistance yielded bit by bit.

‘Lionel! Come and have a look …’

Terray was bending over a container and sorting out provisions in his usual serious manner. He raised his head: it was adorned with a red ski-ing bonnet, and he sported a flowing beard. I asked him point-blank what

his

route was. He had already examined the mountain and come to his own conclusion:

‘My dear Maurice,’ he said, pursing up his lips in the special way that marked a great occasion, ‘it’s perfectly clear to me. Above the avalanche cone of the great couloir, just in line with the summit …’ and he went on to describe the route we had worked out.

So we were all in complete agreement.

‘We must get cracking,’ Terray kept saying in great excitement. Lachenal, no less excited, came and yelled in my ear:

‘A hundred to nothing! That’s the odds on our success!’

And even the more cautious Rébuffat admitted that ‘It’s the least difficult proposition and the most reasonable.’

The weather was magnificent; never had the mountains looked more beautiful. Our optimism was tremendous, perhaps excessive, for the gigantic scale of the face set us problems such as we had never had to cope with in the Alps. And above all, time was short. If we were to succeed not a moment must be lost. The arrival of the monsoon was forecast for about June 5th: so that we had just twelve days left. We would have to go fast, very fast indeed. I was haunted by this idea. To do so we should have to lengthen out the intervals between the successive camps, organize a shuttle service to bring up the maximum number of loads in the minimum time, acclimatize ourselves,

2

and, finally, maintain communications with the rear. This last point worried me. Our party was organized on the scale of a reconnaissance and the total supply at our disposal was only five days’ food and a limited amount of equipment.

How was I possibly to keep track of the thousand and one questions that buzzed round in my head? The rest of the party were all highly excited and talked away noisily while the Sherpas moved about the tents as usual. Only a couple of them were here, and there could be no question of beginning operations with just these two. So the Sahibs would set off alone and carry their own loads: in this way we should be able to get Camp II pitched the next day. When I asked the others what they thought they enthusiastically agreed to make this great effort, which would save us at least two days. Ajeeba would go back to the Base Camp and show the people there the way up to Camp I, which would have to be entirely re-equipped since we were going to take everything up

with

us for Camp II. For Sarki there was an all-important job: he would have to carry the order of attack to all the members of the Expedition.

I took a large sheet of paper and wrote out:

Special message by Sarki, from Camp I to Tukucha. Urgent.

23.5.50

Camp I: Annapurna glacier.

Have decided to attack Annapurna.

Victory is ours if we all make up our minds not to lose a single day, not even a single hour!

Individual Instructions:

Couzy:

Move Base Camp as rapidly as possible and reorganize it, about two hours further on from present site, on a very big and very comfortable site just below an avalanche cone. Bring everything up. Send all high-altitude units to Camp I, as well as all possible food, wireless sets, Gaston’s and my rucksacks, and Lionel’s camp boots. (Give Sarki 15 rupees: you’ll find them at the bottom of my

pied d’éléphant

3

which you must bring up to me.)

Schatz:

If Schatz comes down again from his ridge: organize Camp I, because Biscante, Lionel, Gaston and myself will take everything on to Camp II. The site is marked by a large cairn. It is just on the edge of the glacier. Bring up all possible food and equipment here.

Matha:

Come up quickly. Have got small camera with me. Bring films and send them up to me. Porters can get up to Base Camp; you can leave reserves there.

Oudot:

Come as quickly as possible to Camp I with essential medical supplies; leave further stuff (especially surgical equipment) at Base Camp.

Noyelle:

Most important, without losing a

single hour

, send up to Base Camp: 10 high-altitude containers, 6 valley containers, all high-altitude camping units, the last walkie-talkie, one jerrican of spirit, 2 gallons of petrol, 1 100-foot 8 mm. rope, 2 50-foot 9 mm. ropes, 650 feet of 5 mm. line, 15 ice-pitons, 5 rock-pitons, 10 snap-links, all the head lamps, 2 hanging lamps plus reserve batteries. The Austrian

cacolet

,

4

1 pair skis, 2 pairs ski-sticks, Dufour sledge, everybody’s no. 2 rucksacks, Emerson set with wires, 3 pairs spare Tricouni gaiters, 1 pair

Ours

trousers, 2 valley tents (there will be 3 at Base Camp and 2 at Camp I), 4 pairs boots: 1 size 10, 2 size 9, 1 size 8.

As the valley camping units have got disorganized (sleeping-bags and air mattresses left at Tukucha), bring up what’s necessary to fit them up again.

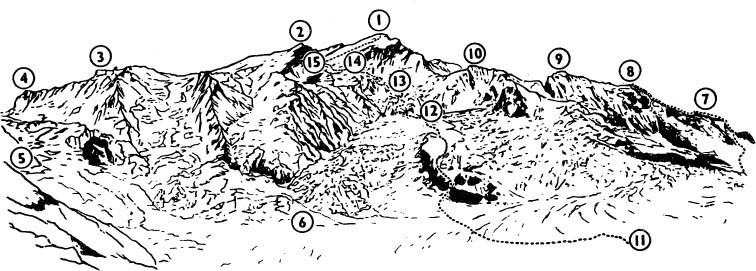

MAIN ANNAPURNA RANGE

- Summit of Annapurna, 26,493 feet.

- East peak.

- The White Table.

- The Black Rock.

- Buttresses of the Great Barrier.

- North Annapurna glacier.

- Route of attempt on north-west spur.

- Subsidiary peak of north-west spur.

- Summit of north-west spur.

- Cauliflower Ridge.

- Camp I, about 16,750 feet.

- Camp II, about 19,350 feet.

- Camp III, about 21,650 feet.

- Camp IV, about 23,550 feet.

- Camp V, about 24,600 feet.

All reserves of gloves and socks – tsampa or rice for the Sherpas. Pack up safely what’s left.

Prepare 10 high-altitude containers and 6 valley containers for future use. A Sherpa could see to bringing these up later.

Come along. Your headquarters will be at Base Camp. G. B. is free to do what he likes.

Matha:

Send a wire to Devies: ‘Camp I at 16,700 feet. Following reconnaissance have decided attack by north Annapurna glacier. Route entirely snow and ice. Weather favourable. All in fine form. Have good hopes. Greetings.’

HERZOG.

The reconnaissance was now being transformed into a definite assault. This order of the day would delight the whole expedition, but I was worried to think that it would take four days for my message to reach Tukucha. I explained as best I could to Sarki:

‘Annapurna,’ I said, pointing to the mountain. ‘

Atcha now!

’

5

‘Yes, Sahib.’

‘All Sahibs go now,’ I said in English, continuing to point to Annapurna.

‘Yes, Sahib.’

‘Like this,’ I said, making as if to run, ‘very quickly to Tukucha for all Sahibs: Couzy Sahib, Doctor Sahib, Noyelle Sahib.’

Sarki’s face was solemn. He had read in my eyes that this was not just an ordinary order; he had understood what I expected of him. He knew we had little food with us and not much equipment, and that if the Sahibs had decided to go up the mountain they must be able to rely upon help from the rear.

Sarki was the most active and the strongest of all our Sherpas, and this mission he was about to undertake was of the very first importance. He stood in front of me, his stomach protruding as though he had a tendency to dropsy, his legs wide apart. His typically Mongolian face was adorned with a blue balaclava surmounted by his dark glasses.

‘Off you go, Sarki! Good luck! It is very important …’ and I shook him by the hand. He did not lose a second; snatched up his things, briefly explained the essential points to Ajeeba in his clipped

guttural

voice, and a few minutes later we saw them go off under the great ice cliff which sparkled in the light, then disappear over the moraine.

After a moment’s silence I turned round to gaze again on Annapurna, all bathed in light. There was not much shadow around us. A few minutes ago we had been shivering, now we had to take off our eiderdown jackets, sweaters and shirts. Dhaulagiri towered in the far distance, nearer at hand were the Nilgiris, and I thought of all that had gone before – the Dambush Khola, the Hidden Valley, the Great Ice Lake, Manangbhot. We were very far from everything that we had foreseen: ‘a light expedition’ – ‘nylon’, as we called it, a really fast expedition. To apply Alpine methods to a Himalayan enterprise – that was the basic strategy of all the plans we had made in Paris. The danger, we had gone on to say, lay in avalanches, so we must stick to ridges. And why arrange a route up the mountain fit for Sherpas? The Sahibs would undertake everything: no Sherpas; hence no need for complications. Heavens, how wrong we had been! Ridges were out of the question. Sherpas? We were not exactly sorry to have them with us. Lightness? Rapidity? The heights are so great that numbers of intermediate camps will always be needed. And then we had not paid sufficient attention to the question of exploration: you arrive in a district, burning with impatience to attack something – yes, but in which direction?

All four of us, Lachenal, Rébuffat, Terray and myself, got our things ready and filled our sacks with as much as we could possibly carry in the way of equipment, food, tents and sleeping-bags, leaving behind only one container with a few accessories which we did not need at once. We shared out the equipment: as usual, some preferred the heavier but less bulky loads, with others it was the opposite. It worked out at an average of about forty-five pounds apiece. At this height, where the least exertion is an effort, we felt crushed beneath our burdens. The straps cut into our shoulders and it seemed a physical impossibility to walk for more than five minutes. All the same we somehow struggled on, for although the packs were far too heavy, we reflected on all the time we were saving.

So the four Sahibs, in single file, and well spaced out on the rope, climbed heavily up through the snow of the great plateau at the

foot

of Annapurna. With the sun vertically above us, the glacier basin was like a furnace, with every ray reflected back from the surface of the snow. Walking soon became a dull agony. We sweated and suffocated. Then we stopped, split open some tubes of anti-sunburn cream and applied the paste thickly to our sweating faces. Lachenal and Rébuffat, who seemed to suffer even more than Terray and myself, made themselves white Ku Klux Klan cowls out of the cotton lining of my sleeping-bag. They assured me that this was admirable protection against sunstroke, but I was not convinced and they seemed to be stifled in them. Terray and I preferred to rely on the cream.