Anonyponymous (11 page)

Authors: John Bemelmans Marciano

While the Irish were starving, the English were getting fat. In 1863, an undertaker and carpenter named William Banting wrote

A Letter on Corpulence Addressed to

the Public

in which he outlined how he had lost fifty pounds in no time at all while eating an extra meal a day and not exercising. He did this by forsaking carbs and sugar; in other words, he did the Atkins diet a hundred years before Dr. Atkins created it. Banting’s self-published pamphlet swiftly became an international phenomenon, finding a success that eluded his American forebear, Dr. Graham. Unlike the Graham diet, however, no religious angle existed in Banting’s—it was just about getting skinnier. “Do you

bant

?” became the question everyone asked each other, at least among the bourgeois set. The verb, sadly, is obsolete today even in British English, though not quite obsolete all together.

Tues·day

n. The third day of the week, and usually the

most boring.

Have you ever wondered how we got the

Tues

- in Tuesday? When Germanic types adopted the Roman week, they decided to make some changes.

Sun-day

and

Moon-day

they translated without prejudice, but for the rest of the week the Teutons wanted their own gods watching over them, and so instead of having the days of Mars, Mercury, Jove, and Venus, they created Tiw’s day, Woden’s day, Thor’s day, and Frig’s day. (For some unknown reason, the Teutons had no problem with Saturn and let him have his day, which is ironic, since in Romance languages Saturn was the one god’s name

not

kept; instead, most adopted some form of the Hebrew word

sabbath

.)

Woden/Wotan and Frig/Fricka will be familiar to lovers of Wagner, as will Thor to aficionados of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby; but who on earth was Tiw? Although god of martial glory (which is why he replaced Mars), Tiw had a rather unfortunate incident with Fenrir, an apocalyptically dangerous wolf. Fenrir broke every shackle put upon him, so the gods of Asgard called upon the dwarves of Svartálfaheim to devise a magic ribbon that was thin as silk, light as air, and unbreakable, which the little fellows fabricated from the breath of fish, a woman’s beard, the sound of a cat’s footsteps, and a few of their other favorite things, none of which exist any longer as a result.

“You’d sure look good in this ribbon,” the gods all told Fenrir, but the wolf, sensing a trap, said he’d only try it on if Tiw held his hand hostage in the wolf ’s mouth. Tiw, brave, honest, and not all that smart, did as the wolf requested. Once the ribbon was on, Fenrir was trapped, and the gods all laughed and kept laughing, even when Fenrir bit Tiw’s hand off. In light of his good faith, Tiw was made the god of oaths, treaties, and contracts. He also became known, aptly enough, as the one-handed god.

tup·per·ware

n. A reusable plastic storage container.

Pedestrian though they seem today, the idea of plastic food containers was so revolutionary in the late 1940s that inventor Earl Tupper had a heck of a time selling them. His patented “burping seal”—that guarantee of freshness—baffled consumers. Mr. Tupper’s product might never have taken off if not for Brownie Wise, a preternaturally well-named single mother from Detroit who started selling Tupperware at social gatherings and soon was encouraging other women to follow her example. So successful was Wise that in 1951 Tupper pulled his product out of stores and put all sales directly into her hands.

Although today thought of as a quaint relic of the preliberated housewife, the Tupperware party was in fact a progressive step, as all over America (and soon the world) housewives got a taste of entrepreneurship and cold, hard cash. Selling Tupperware was about making money, and more: Wise was a female Norman Vincent Peale who dared women to dream and offered them the “suffrage of success.” She herself took to that freedom with glad alacrity, tooling around in a pink Cadillac and becoming the first woman to appear on the cover of

BusinessWeek

. Jealous of her fame, Tupper fired her. Shortly thereafter, the inventor divorced his wife, sold his company for sixteen million dollars, gave up his U.S. citizenship for tax purposes, and moved to Costa Rica, where he would die in obscurity.

ves·pas·ian

n. A kind of public urinal found on the streets

of Latin-speaking countries. Literally,

on

the streets.

A man like Vespasian might have been remembered for lots of things: the construction of the Colosseum, the putdown of revolts in the Judea, the conquering of new lands in Britain. Instead, the name of this first-century Roman emperor will forever be connected with the Urine Tax.

Coming out the victor in the Year of the Four Emperors (as chaotic a time as its name implies), Vespasian was faced with some serious budget shortfalls. One major untaxed natural resource was urine. Cleaners needed fermented urine—ammonia—in order to keep their customers’ togas a sparkling white, so they posted buckets outside their doors into which passersby could relieve themselves. Knowing a golden revenue stream when he saw one, Vespasian taxed the cleaners on the piss they collected. When the emperor’s son Titus told his father he found the tax repulsive, the old man held out a gold coin for Titus to sniff and said, “Money don’t stink.”

volt·age

n. An amount of energy, often figurative.

Born and raised in the idyllic lakeside city of Como, Alessandro Volta began his career as a high school physics teacher with a passion for electricity. His first advances were made in developing the electrophorus, a device that produced a static electric charge, and he also liked to play around with exploding gases (his favorite being methane, which he is credited with “discovering”). Investigating the work of Galvani and his famous frog, Volta rejected his colleague’s theory of animal electricity and countered what he termed “galvanism” with his own theory that electric current was produced by the contact of two different metals. Upon this principle, Volta developed the world’s first battery in 1800. The following year, he demonstrated his invention to Napoleon, who rewarded Volta by making him a count.

Between them, Volta and Galvani did more than anyone else to usher in the age of electricity, and left their mark not only on science and language but also literature: It was after discussing galvanism that Mary Shelley came up with the idea for

Frankenstein

.

wimp

n. A wuss.

The original wimp was J. Wellington Wimpy, the porkpie-hatted mooch of the Popeye cartoons, whose perennial gambit “I would gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today” never quite succeeded.

E. C. Segar’s

Thimble Theatre

, the comic strip in which Popeye first appeared, is remarkable for its contribution to the lexicon. In addition to

wimp

, Segar is also responsible for the word

goon

, from his hairy warrior woman Alice the Goon, and probably the vehicle name

Jeep

, after Olive Oyl’s pet Eugene the Jeep, a magical and resourceful creature from the fourth dimension whose entire vocabulary consisted of the single word “Jeep!”

zep·pe·lin

n. A dirigible airship; best when not filled with

hydrogen.

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin caught the aviation bug when he was a military observer attached to the Union Army Balloon Corps. The chief mission of President Lincoln’s aeronauts was to provide reconnaissance, but von Zeppelin came away convinced that aircraft could do more, provided they became engine-powered and steer-able. His answer was a motor-powered balloon with a hard shell, called a dirigible (as opposed to a nonrigid airship, or blimp). Von Zeppelin’s first successful flight didn’t come until 1900, but just nine years later the count produced a model that reached speeds of fifty miles per hour and would go on to stock the fleet of DELAG, the world’s first commercial airline.

Zeppelins were soon carrying out air-raid missions— another first—but their success in such capacity was short-lived once the getting-bombed-upon Brits realized that dirigibles were just big balloons waiting to be popped by gunfire. The postwar era would prove the golden age of the zeppelin, as airships competed with ocean liners for the transatlantic passenger business, matching them in luxury and, flying at a pleasant low distance above the ground, offering the advantage of sightseeing. Zeppelin routes went as far afield from Germany as Brazil, and the spire of the Empire State Building was designed to moor dirigibles. (The 102nd floor was to be the landing platform, but it didn’t work.)

The death of the zeppelin came with the spectacular 1937 Hindenburg disaster that took place over Lakehurst, New Jersey. The Nazis were using zeppelins for propaganda (much as Goodyear would in later years), but they had no access to helium; only the U.S. possessed the gas in industrial quantities, and they weren’t selling, at least not to Hitler. Some

dummkopf

decided to fill the eight-hundred-foot-long Hindenburg with the highly flammable gas hydrogen, and the rest, as they say, is history.

* Duns

, by the way, is pronounced the same as

dunce

, its spelling an obsolete convention also seen in

ones

and

twys

(

once, twice

).

* My own wife is named after Hector’s bride, the princess of Troy, Andromache. Hi, honey.

* This phrase, coined by Mesmer, had nothing to do with animals but with

anima

, the Latin word for soul.

* Rhymes with Conan, as in O’Brien, not the Barbarian.

* For trademarks staving off genericide, see

frisbee, jacuzzi,

and

tupperware

; for one already expired, see

zeppelin.

*

Archons

were the magistrates of Athens, and the chief among them was the

Archon Eponymos

, so-called because the year in which he served was named after him.

* “The Kinquering Congs Their Titles Take.”

ANONYPONYMS

SANS FRONTIERES

A zeppelin is a zeppelin in languages across the world, except when it’s not. The standard term is often some form of the word

dirigible

. A reverse situation holds for the airship’s aimless cousin: What we call a hot-air balloon is known in other countries for the French brothers who invented it.

Although an American education might have you believe that the first men to fly were the Wright brothers, another pair of brothers beat them to the punch—by 120 years. Joseph and Jacques Montgolfier created the vehicle that produced the first manned flight in 1783, a balloon given lift by what the brothers called Montgolfier Gas. (It was just plain air, lest you think they produced gas in some other manner.) Their first flight crew consisted of a duck, a rooster, and a sheep; seeing their barnyard trio survive, the brothers sent humans skyward. Their creation is known as a

montgolfier

in French and a

montgolfi

ere

in Italian.

Trademarked names have taken root in languages everywhere, but even with global brands acceptance varies from country to country. You can take a

yacuzzi

in Spain or a

jacuzzibad

in Sweden, but in Portugal and Germany you’ll have to settle for a

banho de hidromassagem

and a

Sprudelbad

. A ballpoint pen is a

biro

in many parts of the world (Britain and Australia included), for its inventor László Biró, or a

bic

, after Marcel Bich, a Frenchman who licensed the technology from the Hungarian Biró. (Monsieur Bich was afraid his name would be mispronounced

Bitch

in anglophone countries, hence the spelling change.)

The eponyms used most widely and consistently come from the international world of science. A volt is a volt wherever you go, as are the psychological conditions of masochism and sadism (more or less). There’s a division, however, with

X-ray

. The Romance languages are in sync with the English formulation (e.g., the Spanish

rayos X

), which was coined by the discoverer of the X-ray, Wilhelm Röntgen, who in 1895 took the first X-ray photograph. (It was of his wife’s hand.) His native tongue, however, ditched the doctor’s suggestion and chose instead to honor Wilhelm himself, and so an X-ray is a

Roentgen

in German, as it is in most languages across northern and central Europe.

Medical terms tend to get discarded once the theories behind them have been discredited, as in the English-speaking world with

onanism

and the implication that masturbation is a wasting affliction. It remains standard usage, however, in countries such as Sweden (

onani

) and Germany (

Onanie

).

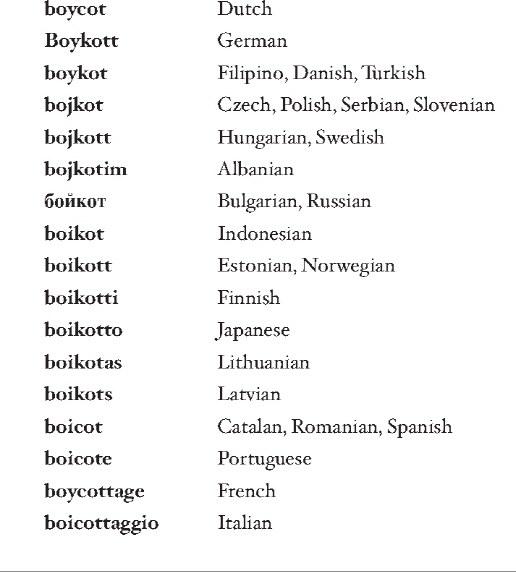

More resilient have been certain political anonyponyms that spread like wildfire because they so captured a moment and continue to be relevant today. People around the globe have no more idea of who Charles Boycott was than English speakers do, but what’s striking about his word is the level of adoption it achieved, and how swiftly. Less than fifty years after the first boycott, the government of propagandist extraordinaire Benito Mussolini launched a political campaign to banish all nonnative words—

le parole stranieri

—from the Italian vocabulary. For example, a

croissant

by law had to be called a

bombola

. And the slogan on posters? ITALIANI, BOICOTTARE LE PAROLE STRANIERI!

Another political eponym,

chauvinism

, became useful in the face of nationalist movements that upended the world in war and strife—and found itself transformed into Polish

szowinizm

, Czech

šovinizmus

, Indonesian

sovinisme

, and Filipino

tsowinisma

, to name a few. It should be noted that the sexist connotation English chauvinism has taken on is missing in other languages. The Italian

sciovinismo

refers to excessive patriotism or partisanship, while what we would call male chauvinism is there styled

maschilismo

(formed in opposition, naturally, to

femminismo

). To mesmerize means to spellbind in English, but in other tongues remains a synonym for

hypnotize

, or is relegated specifically to the practices of Franz Mesmer. Sometimes figurative meanings wander quite far afield. A judas is a traitor in many languages, but in French it refers to a peephole, betrayer of the person being spied upon.

Literary eponyms are less likely than others to cross borders, excepting those based on widespread classics such as

Don

Quixote

, attested to by English

quixotic

, Spanish

quijotesco

, and the arabesque Italian adverb

donchisciottescamente

. (In Italian, Cervantes’s work is

Don Chisciotte

[key-SHOAT-tay], if that helps parse it.) As for a word from an English book,

lolita

is spreading fast, more so in other languages than in the one it was written in. Generally it means a sexually precocious or aggressive young girl, although in Japan the word has come to represent a goth fashion style.

Ludwig Bemelmans’s 1941 travel book

The Donkey Inside

produced a word unique to the Spanish of Ecuador,

bemelmans

, which means “foreigner who makes fun of natives.” A sampling of text that might have offended: “We have a revolution here every Thursday at half-past two, and our government is run like a nightclub.”

A number of people live on in other languages but not their own.

Martinet

as an eponym does not exist in the drillmaster’s native tongue, although French has a word

chatterton

that means electrical tape after its British inventor, while

bant

endures in Swedish as the word for dieting. And though Pullman (after George, developer of the sleeper car) has faded from the English vocabulary along with the tendency to take overnight train rides,

pullman

(pronounced POOL-mahn) has spread to become the general Italian word for bus.

I’d like to end our linguistic tour by nominating a particularly handy word for English-language adoption. Johann Ballhorn, a printer during the last quarter of the sixteenth century, was responsible for publishing an important law book for his home city of Luebeck. In the process of correcting an earlier edition—a typical task of the printer in those days— Ballhorn wound up making mistakes where none had earlier been, thereby causing a legacy of legal disputes and bequeathing to German a verb,

verballhornen

, “to make worse through correcting.”