Anonyponymous (12 page)

Authors: John Bemelmans Marciano

EPONYM WATCH LIST

Most eponyms die. Few outlive the fame of the people who birthed them, and most fade even faster. Some are superseded by synonyms while others become technologically obsolete, as is the case with the

brougham

,

hansom

, and

phaeton

, three types of horse carriages named after a couple of Englishmen and a kid who wrecked his father’s wheels. Fiction-based eponyms depend largely upon the vagaries of literary taste. In this respect no one has suffered more than Charles Dickens, once the most widely read writer in the English language, now falling off reading lists everywhere. A

scrooge

is known to all and a

fagin

understood by many, but who still knows what

gamp

,

peck-sniffi

an

, or

gradgrind

mean? (If you want to be the one, they are: an umbrella, after Sarah Gamp of

Martin Chuzzlewit

; hypocritical, for Seth Pecksniff of same; and a man given to facts, such as Thomas Gradgrind in

Hard Times

.)

Below find some eponyms lamentably lost or seriously imperiled. Language is what its speakers make it, so you have power to revive them.

annie oakley

Annie Oakley, the sharpshooting star of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, had her own breed of card tricks. At a distance of thirty paces, she could shoot out the heart in the ace of hearts, split a playing card in half with a bullet edgeways, and shoot half a dozen holes into a card tossed into the air before it hit the ground. Her name came to mean a free ticket or pass, as in one that’s already been punched.

Status: defunct

baedeker

A guidebook, after the widely read publications of Karl Baedeker, whose company started producing travel manuals in 1827. The “Baedeker raids” of World War II were so-called because the Germans struck at historical sites featured in

Baedeker’s Great Britain

.

Status: faint pulse

give a bell

Alexander Graham Bell was literally an eponym machine, bequeathing Ma Bell, the Baby Bells, decibel, and this term, for calling someone on the phone.

Status: under revival

bogart

Humphrey Bogart has the distinction of

two

English verbs springing from his surname. The first means to act like a tough guy or intimidate, as in, “Don’t bogart your little brother.”

Status: died out a generation ago

The second verb, meaning to steal something in small increments, went mainstream in the sixties time-capsule movie

Easy Rider

. “Don’t bogart that joint, my friend . . . ” begins the chorus of the song playing while Jack Nicholson rides on the back of Peter Fonda’s chopper. Its extended sense of “to be greedily protective of something” has lately been moving the verb out of its cannabis pigeonhole, which speaks well for its prospects for long-term survival (as does the fact that most people using it have never seen the Humphrey Bogart smokefest known as

Casablanca

).

Status: burgeoning

pull a brodie

To commit suicide, usually figuratively, coined in 1886 after Steve Brodie jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge to win a bet and survived. Although his feat was considered by many a hoax, Brodie parlayed his fame into a touristy saloon on the Bowery and acting gigs in a couple of vaudeville shows. He was later portrayed in the movies by George Raft and served as Bugs Bunny’s foil in “Bowery Bugs.” (Out of sheer exasperation with the rabbit, he jumps off the bridge again at the end.)

Status: jumped the shark long ago

burke

When an old man died owing back rent at his Edinburgh boarding house, landlord William Hare hit upon a unique way of getting the money out of him: selling the deadbeat’s corpse. With his friend William Burke, Hare stole the body out of its coffin and brought it to the local anatomy school. Seeing how well it paid, the duo entered into the dissection-supply business. Turning the lodging house into an operation Procrustes would have admired, Hare and Burke murdered at least fifteen transients before getting caught Halloween night, 1828. The evidence was circumstantial, but in turn for immunity Hare confessed, which is why he walked free and his pal got hanged, and the verb meaning “to smother to death or hush up” is to

burke

and not to

hare

.

Status: worth reviving

not to be grahamed

Giuseppe Mazzini was the intellectual father of the Risorgimento, the Italian unification movement. A philosopher and agitator with a death sentence hanging over his head, in 1837 Mazzini settled in London, a city that prided itself for its fair treatment of political exiles. When the British government was discovered to be opening Mazzini’s mail, the scandal was blamed on Home Secretary James Graham, and Britons began writing not to be grahamed on their envelopes in elegant protest.

Status: extinct

lindbergh it

To go solo, as in out to dinner, or wherever.

Status: my mother still uses it

lucy stoner

A slur targeting a woman who doesn’t take her husband’s name, coined after the marriage of suffragette Lucy Stoner in 1855. The surname Ms. Stoner chose not to take: Blackwell.

Status: historical use only

mae west

An inflatable life preserver. Get it?

Status: deckside humor on senior cruises

mickey

As in, to be slipped a mickey, or—to use the full expression—a Mickey Finn, meaning a drink that’s been laced with a knockout drug or hallucinogen; by extension, a real strong drink. The original Mickey Finn owned the Lone Star Saloon in turn-of-the-century Chicago; he would rather ungraciously sedate his customers in the aforementioned manner, rob them, and dump their unconscious bodies in an alley (but hey, at least he didn’t burke them). The saloon was shut down and Finn convicted in 1903, done in by the testimony of his accomplices, “house girls” Isabelle Fyffe and Mary “Gold Tooth” Thornton.

Status: annoying hipster use

milquetoast

Caspar Milquetoast was everything you might expect from the protagonist of a comic strip entitled

Timid Soul

, created in 1924 by H. T. Webster.

Status: dated

pinchbeck

Counterfeit, false, cheap, worthless, tawdry. Christopher Pinchbeck was a London watchmaker in the early 1700s who marketed jewelry made out of imitation gold, the alloy of which (lots of copper and a bit of zinc) he developed himself.

Status: used in intellectually elitist periodicals

When I was little, my mother told me that the word

pumpernickel

came from the name of Napoleon’s horse, Nickel. While encamped in Germany, Napoleon’s soldiers complained about the indigestible local black bread. Napoleon responded that his horse liked the stuff well enough. “If it’s

bon pour Nickel

,” the little Corsican said, “then it’s good for you too.”

Sadly, the tale is utterly apocryphal. The origin for the name likely comes from

pumper

, a German word meaning “fart.” It is one of many enticing word stories I would have loved to include in the book but couldn’t.

People have postulated that the term

jerry-built

refers to the handiwork of a Jerry Bros. construction firm that put up exceptionally shoddy housing in late-1800s London, but they offer no proof. Eponym hunters have also searched the world for the first person to be

batty

and turned up two plausible candidates: one, Jamaican barrister Fitzherbert Batty, declared legally insane in the 1800s; and two, William Battie, eighteenth-century author of

A Treatise on Madness

. So which is the right one? Neither. The word derives from the phrase “bats in the belfry.”

Historians have cried eponymy to discredit subjects they don’t like. In his work of the 1570s,

Perambulation of Kent

, William Lambarde wrote that the first

harlot

was Arlette, mother of William the Conqueror, known to chauvinistic Englishmen as William the Bastard. Lambarde was nursing a grudge over the 1066 Norman invasion but most probably believed the etymology; certainly it has been cited countless times in the four centuries since. However, to look at a passage from Chaucer—“A sturdy harlot went them aye behind, / That was their hoste’s man, and bare a sack, / And what men gave them, laid it on his back”—we see that the word previously meant a different kind of worker.

At least

harlot

has a reasonable false etymology; other would-be eponyms are plain silly.

Condom

has been said to derive from either a Dr. Condom, personal physician to King Charles II of England, or the Earl of Condom. There is no Condom in Britain to be an Earl of, nor is Condom a known English surname, although Condon is, which is how the prophylactic was sometimes spelt in the 1700s. But in the earliest extant reference the spelling is

quondam

, leading to the suggestion that it is derived from the Italian word

guantone

, which roughly translates to “a big glove.” In short, the etymology is unknown, but hope remains alive that we will find a lusty but careful Mr. Condon out there.

Great long lists of eponyms can be found all over the Internet, some so loaded with counterfeits that more than half the names are phonies. But even one conscientious site has, among hundreds of accurate entries, the apocryphal figures Nathaniel Bigot (said to have been an English Puritan teacher), a Portuguese man named João Marmalado, and Leopold von Asphalt.

My favorite fraud is the esteemed Dominican scholar Domenico da Comma (1260–1316). This Italian monk inserted his namesake commas into the heretofore woefully under-punctuated Bible to make it more readily comprehensible. For his efforts, da Comma was charged with heresy by the Inquisition, who considered his editorial improvement “an affront to God.” If only it were so; the word instead comes from the Greek

komma

, cut off.

But things are not always so clear, nor is it only the Internet that gets things wrong. Was Nicholas Chauvin a real person? No one knows, but he is almost always cited as such. Thomas Crapper is often thought to belong on da Comma’s list because of a comically grand pseudobiography,

Flushed with

Pride

, that made him seem entirely made-up. More often than whether a person existed, however, the question is whether we’ve found the right one. For

lynch

, different reference works definitively support Charles (

Encyclopaedia Britannica

) and William (

Oxford English Dictionary

).

Then there’s the question of whether a word is an eponym at all, which often comes down to a matter of personal prejudice. Killjoy etymologists cite antebellum uses of the word

hooker

in the sense of “prostitute” as gotcha-game proof that the word is noneponymous. But without Hooker’s Division would the term have endured? Lord knows we have enough synonyms to get by. All words—and proper names are words— go back to some earlier word, so to put too much weight on the “original” source is to be simplistic.

Even when eponymy is certain, much else is not. Myths inevitably pop up to fashion people with more direct roles in the creation of what bears their name: The derby was first worn by the Earl of Derby to his horse race (false); Silhouette practiced the art of shade cutting (seems unlikely); Cardigan invented the sweater he and his men wore into battle (almost assuredly not); Saint Audrey had a neck tumor, which is why a gaudy neckerchief was named after her (surprisingly true, or the Venerable Bede is a liar).

In many cases, the legend itself is what’s important. Whether or not Chauvin existed is meaningless for its development as a word. This is true of more than folklore; historians gossip, too, and not just William Batarde. Wanting to show the Bourbon kings to be spineless creatures controlled by their mistresses, nineteenth-century historians inflated Madame de Pompadour’s role in national affairs. In the matter of her enduring fame, the myth of La Pompadour is at least as significant as the woman born Jeanne Antoinette Poisson.

While the power of popular perception is important, I put nothing in this book that to my better knowledge wasn’t true, with one exception: the tale of our old friend, the Earl of Sandwich.

The mythology of the earl inventing sandwiches to get through a daylong gambling binge seems to have formed around a single source. It appeared in a travel book on London written by a visiting Frenchman who was repeating something juicy he had heard about one of the king’s ministers. There’s no corroborating evidence that the earl was a gambler of any sort; rather, he was said to be a tireless worker, leading to the conjecture that maybe he loved his sandwiches because they allowed him to

work

through the night, a claim proposed by his biographer and supported by his descendants (owners of the Earl of Sandwich restaurant chain), which seems only slightly less ridiculous than the Frenchman’s tale.

In either event, what does it matter? It’s just a macguffin.

Philadelphia whiskey maker E.G. Booz: His product was memorably packaged in a log-cabin-shaped brown bottle;

to bouse

as a verb goes back to Middle English.

algorithm

. . . Algorismus: The term

algorithm

developed after

algorism

(the original English word) got confused with

arithmos

, the Greek word for number.

scientific pig Latin: The naming system Linnaeus developed, set forth in his

Species plantarum

(1753) and

Systema naturae

(1758, tenth edition), includes a generic (genus) name and specific (species).

nearly thirty times what they were worth: The harvest reportedly cost the British government £10,000 for £350 worth of potatoes. “Boycott’s legacy; Making a name for himself: British land agent Captain Charles Boycott was ostracised by the Irish.”

Daily Mail

(September 27, 2007).

Improving upon Jackson’s idea: Kellogg got his original start in the cereal business producing his own version of Granula, called Granula. Upon Jackson’s apparent threat to sue, Kellogg renamed his product Granola. A former patient at John’s sanitarium named C.W. Post then ripped off

Kellogg’s

Granola recipe, creating Grape Nuts. Years later, hippies would revive the name of Kellogg’s by-then defunct product for a new take on the cereal genre.

brought back home with them a new word: That, at least, is one theory, based on chronology and geography. To wit: Crapper went into business in 1861; the OED cites “crapping ken” (1846), “crapping case” (1859), and “crapping-castle” (1874) as referring to outhouses and water closets, but

crapper

is first seen in American slang from the 1920s. The link from Thomas Crapper to the Americanism, if real, is yet to be discovered.

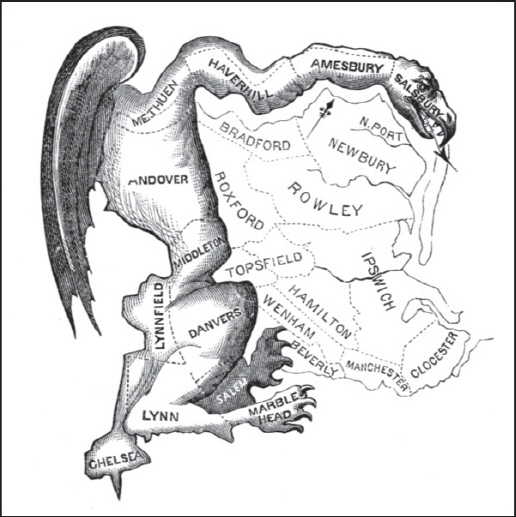

“That will do for a salamander!”: A salamander is a variety of amphibian, but was long the name for a mythological, lizardlike creature that lived in fire and was closely related to the dragon. On Elkanah Tisdale’s original drawing of the gerrymander, notice the silhouette of Governor Gerry under the beast’s wing.

the lexical contributions: The term

superman

itself is not originally an eponym, but was coined by Friedrich Nietzsche (or, rather, his translators). Still, it’s safe to posit that when someone says “Don’t try to be a superman,” they aren’t talking about the proto-Nazi übermensch but rather the creation of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, a couple of nice Jewish boys from Cleveland.

an amalgam of

brain

and

maniac

: The famed supercomputer ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Automatic Calculator), built in 1946, also may have influenced the character’s name.

Bizarro: The word

bizarre

may come from the language linguists consider the bizarro world, Basque, where the word

bizzara

means “beard.”

one Scuttled Butt

: A scuttlebutt was the deckside equivalent of the water cooler, literally and figuratively. Vernon’s order appears in Michael Quinion’s essay on grog (“World Wide Words: Grog,” World Wide Words,

www.worldwidewords.org/qa/qa-gro4.htm

), as well as in Peter D. Jeans,

Seafaring Lore and Legend: A Miscellany of Maritime Myth, Superstition, Fable,

and Fact

(McGraw-Hill Professional, 2004): 101–102.

“Old Grog”: Grogram, from French

gros grain

, is a coarse fabric out of which were made cloaks and coats, often themselves called “grograms” by synecdoche. Vernon’s ever-present grogram earned him the nickname Old Grog.

adopted, with vigor: Though often credited with the invention of the guillotine, Joseph-Ignace only proposed the device; its roots are centuries older. The version used in Revolutionary France was designed by Dr. Antoine Louis (who would die by one) and built by German harpsichord maker Tobias Schmidt. It quickly took on innumerable nicknames, among them the Louisette, the Louison, the widow, the national razor, the Capetian necktie, Guillotin’s daughter, Mlle. Guillotin, and, of course, the guillotine. Supposedly, the Guillotin family lobbied to change the name of the device and, that failing, changed their own.

“bar-room and brothel”: A grandson and great-grandson of presidents, Charles Francis Adams Jr. described Hooker’s headquarters as “a place where no self-respecting man liked to go, and no decent woman could go . . . a combination of bar-room and brothel.” Hugh Rawson, “Why Do We Say That?”

American Heritage

(Feb./March 2006): 16.

Hooker ordered that prostitutes: According to Thomas Power Lowry,

The Story the Soldiers Wouldn’t Tell

(Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1994): 64, “To aid the military police by localizing the problem, Hooker herded many of the prostitutes into the Murder Bay (future Federal Triangle) area.”

regional slang term: Three antebellum citations have so far been found for

hooker

, two of which independently ascribe its origin to Corlear’s Hook, a bawdy part of New York filled with sailors and brothels. Some think the word evolved from an earlier sense of

hooker

as a pickpocket, or the idea of a prostitute trying to “hook” a client. Likely, it was some combination of these elements, and the use of

hooker

formed a double or triple entendre— one of the entendres being Fighting Joe.

Patrick Hooligan: In 1898, tales of “Hooligan” gangs began appearing in London newspapers. A variation on the more familiar Houlihan,

hooligan

almost certainly derives from someone’s name, but whose is in dispute. The main evidence for Patrick comes from Clarence Rook’s

The Hooligan

Nights

(New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1899), which recounts his story as told by patrons of the Lamb and Flag, a pub Hooligan frequented.

it kind of sounded African: A variety of African connections have been suggested, including a link to the Swahili word

jumbe

, or chief, and a possible connection to the West African bogeyman Mumbo Jumbo. According to the writer Jan Bondeson, the London Zoo superintendent who named Jumbo also later named an African gorilla Mumbo.

The Feejee Mermaid

and Other Essays in Natural and Unnatural History.

(Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999): 99.

“The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze”: Composed in 1867, with words by Gaston Lyle and music by George Leybourne. From Howard Loxton,

The Golden Age of the Circus

, (New York: Smithmark Publishers, 1997): 68:

He flew through the air, with the greatest of ease

This daring young man on the flying trapeze;

His movements so graceful, all girls he could please

And my love he purloined away.

poor Jules died at thirty-one: The year of Léotard’s birth, and his age at death, are in dispute. While many sources agree that he was born August 1, 1838, the years 1842 and 1839 have also been suggested. He died in 1870.

So which Lynch was it?: Charles was long considered the real Lynch, then the pendulum swung to William and has only in the last couple of years swung back to Charles. Much about the William thesis is easy to dismiss, since it rests on documents published long after the term entered the language (an 1811 account of Lynch’s confession to South Carolina diarist Andrew Ellicott, an 1836 article in the

Southern Literary Messenger

, and a May 1859 article in

Harper’s

magazine). Christopher Waldrep has provided essential research bolstering the Charles thesis, and was the source for much of this entry. See Christopher Waldrep,

The Many Faces of Judge

Lynch: Extralegal Violence and Punishment in America

(New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), and

Lynching in America: A History in Documents

(New York: New York University Press, 2006).

a hoax perpetrated by Edgar Allan Poe: Poe loved hoaxes, especially those he managed to get published in the newspaper. In 1844, he persuaded the

New York Sun

to publish an entirely false account of a European who had managed to cross the Atlantic in three days in a hot-air balloon.

The Milliner’s Trade: The term milliner derives from those famed pliers of fancy wares (originally not just hats) of Milan.

the Southwark hatters who manufactured it: Other versions of the story say the name derives from the hatter John Bowler, and that it wasn’t William who ordered the hat but a relation, Edward Coke.

Alexander Pope’s

Dunciad

: The

Dunciad

, first published in 1728, was an epic parody in which Pope eviscerated many of his fellow authors of the day, whom he fashioned “dunces” living in the kingdom of Dulnes. By that time a dunce meant a general blockhead, though according to the Oxford English Dictionary Pope was also using the term with the special sense of one who has been made stupider by learning.

sark

:

Sark

is cognate with the second half of

berserk

, Icelandic for bear-shirt, the dressing preference of some particularly bloodthirsty Viking warriors.

Cutty Sark

became the name of a nineteenth-century clipper ship that in turn inspired a brand of whisky.

slave signed the document “Dr. Leopold, Knight of Sacher-Masoch”: Leopold von Sacher-Masoch,

Venus in Furs

. Trans. Jean McNeil, in

Masochism: Coldness and Cruelty & Venus in Furs

(New York: Zone Books, 1991): 278–279.

trance states: Mesmer was hypnotizing people without knowing it and “curing” them via hypnotic suggestion. He was no charlatan; he wanted badly to be investigated, believing he had made great scientific breakthroughs. Since the Mesmer commission, faith healing has been shown to be effective, while energy flow and magnet wearing (both with long histories pre-Mesmer) are back in vogue.

ironically for the monarch: Destined to die on Guillotin’s machine along with the king was his wife, Marie Antoinette (a client of Mesmer’s), as well as the chemist Antoine Lavoisier, a member of the commission.

the obvious reading of Genesis 38: Modern biblical scholarship tends to say Onan’s crime was his failure to fulfill the obligation of levirate marriage, an ancient Hebrew custom that required a man to marry his brother’s wife if the brother died without a male heir.

call them all—Pandars!

: Obviously, not quite prescient enough. The term

pander

changed again post-Shakespeare. As a verb,

pander

went from meaning to act as a go-between for sex to a figurative use, associated especially with politicians. That verb then produced a noun,

panderer

, with a different meaning from the original noun

pander

. Today the meaning of

pander

as “to pimp” exists only as a relic in U.S. legal code.

paparazzi

has entered the world lexicon: In Japan, mothers who photograph their children’s every move are called

mammarazzi

, a term making inroads in English as well.

statue of a warrior: The statue is thought to represent Menelaus (cuckolded husband of Helen of Troy) carrying the body of Patroclus (Achilles’ boon companion and boy toy).

a really silly fifties hairstyle: The coiffure, in a slightly different form, was first worn by La Pompadour and copied by men as well as women. The style had several variations but always involved sweeping the hair up off the face, and sometimes even fixing it to a wire frame.

Procrustes: In Greek,

Prokroust

e

s

literally means “the stretcher.” The serial killer’s real name, according to Apollodorus (the first known to write about him), was Damastes, though others have suggested the name Polypemon.

lacking the death penalty: Norway had not had a civilian execution since 1876, but capital punishment was still on the books for the military, where it remained until 1979.

when Nellie had a spell under the weather it was the one thing she could eat: Another story has it that the opera diva was on a diet and one day her thin dry toast arrived overdone, horrifying Escoffier, but Nellie wound up liking it that way. Melba, Dame’d in 1918, was born Helen Porter Mitchell; her stage name derives from her hometown of Melbourne, Australia.

Lemuel Benedict: His story, which he told the

New Yorker

in 1942, could well be a tall tale. There are many contenders to the plate. The original server of the dish may have been Delmonico’s (with the name eggs à la Benedick), or perhaps a French provincial dish called

oeufs bénédictine

is the source of the recipe. Then again, maybe Delmonico’s and French peasant cooks are a bunch of copycats.

(but no anchovies): Some say a salad with anchovies came first, whipped up by Cesare’s brother Alex. However, others attribute the dish to chef Giacomo Junia of Chicago, who is said to have created it around 1903 and named it after Julius Caesar.

the crime of “moderatism”: In a political sense, that is.

de Sade, by the way, was really fat: And short. But to be fair, it was only late in life that he “had eaten himself into a considerable, even a grotesque, obesity,” as de Sade biographer Neil Schaeffer wrote in the

Guardian

in 2001.

Shrapnel: The meaning of the word extended from the shell to the projectiles it sent forth, and in that sense endured after the shell itself became obsolete technology. In Aussie and Kiwi military slang,

shrapnel

took on a further figurative meaning, of small bills or change.