B0041VYHGW EBOK (112 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

6.161

October.

6.162

October.

6.163

October.

Moreover, the cutting contrasts shots of the cannon slowly

descending

with shots of the men crouching in the trenches looking

upward

(

6.155

,

6.156

). In the last phase of the sequence, Eisenstein juxtaposes the misty, almost completely static shots of the women and children with the sharply defined, dynamically moving shots of factory workers lowering the cannon

(

6.164

).

Such graphic discontinuities recur throughout the film, especially in scenes of dynamic action, and stimulate perceptual conflict in the audience. To watch an Eisenstein film is to submit oneself to such percussive, pulsating graphic editing.

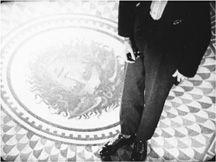

6.164

October.

Eisenstein also makes vigorous use of temporal discontinuities. The sequence as a whole is opposed to Hollywood rules in its refusal to present the order of events unambiguously. Does the crosscutting of battlefield and government, and factory and street indicate simultaneous action? (Consider, for example, that the women and children are seen at night, whereas the factory appears to be operating in the daytime.) It is impossible to say if the battlefield events take place before or after or during the women’s vigil. Eisenstein has sacrificed the delineation of 1-2-3 order so that he can present the shots as emotional and conceptual units.

Duration is likewise variable. The soldiers fraternize in fairly continuous time, but the Provisional Government’s behavior presents drastic ellipses; this permits Eisenstein to identify the government as the unseen cause of the bombardment that ruptures the peace. At one point, Eisenstein uses one of his favorite devices, a temporal expansion: there is an overlapping cut as a soldier drinks from a bottle. The cut recalls the expanded sequence of the wheel knocking over the foreman in

Strike

(

6.44

–

6.46

). At another point, the gradual collapse of the women and children waiting in line is elided. We see them standing, then later lying on the ground. Even frequency is made discontinuous: it is difficult to say whether we are seeing several cannons lowered off the assembly line or only one descending cannon shown several times. Again, Eisenstein seeks a specific

juxtaposition

of elements, not obedience to a time line. Editing’s manipulation of order, duration, and frequency subordinates straightforward story time to specific conceptual relationships. Eisenstein creates these relations by juxtaposing disparate lines of action through editing.

Spatially, the

October

sequence runs from rough continuity to extreme discontinuity. Although at times the 180° rule is respected (especially in the shots of women and children), never does Eisenstein begin a section with an establishing shot. Reestablishing shots are rare, and seldom are the major components of the locales shown together in one shot.

Throughout, the classical continuity of space is broken by the intercutting of the different locales. To what end? By violating space in this manner, the film invites us to make emotional and conceptual connections. For example, crosscutting to the Provisional Government makes it the source of bombardment, a meaning reinforced by the way the first explosions are followed by the jump cut of the government flunky.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

We give several examples of striking and effective cuts in “Some cuts I have known and loved,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=2346

.

More daringly, by cutting from the crouching soldiers to a descending cannon, Eisenstein powerfully depicts the men being crushed by the war-making apparatus of the government. This is reinforced by a false eyeline match from soldiers looking upward,

as if

at the lowering cannon—false because, of course, the two elements are in entirely separate settings (

6.155

,

6.156

). By later showing the factory workers lowering the cannon (

6.164

), the cutting links the oppressed soldiers to the oppressed proletariat. Finally, as the cannon hits the ground, Eisenstein crosscuts images of it with the shots of the starving families of the soldiers and the workers. They, too, are shown as crushed by the government machine. As the cannon wheels come ponderously to the floor, Einstein cuts to the women’s feet in the snow, and the machine’s heaviness is linked by titles (“one pound,” “half a pound”) to the steady starvation of the women and children. Although all of the spaces are in the story, such discontinuities create a running political commentary on the story events.

In all, then, Eisenstein’s spatial editing, like his temporal and graphic editing, constructs correspondences, analogies, and contrasts that ask us to

interpret

the story events. The interpretation is not simply handed to the viewer; rather, the editing discontinuities push the viewer to work out implicit meanings. This sequence, like others in

October,

demonstrates that there are powerful alternatives to the principles of classical continuity.

When any two shots are joined, we can ask several questions:

- How are the shots graphically continuous or discontinuous?

- What rhythmic relations are created?

- Are the shots spatially continuous? If not, what creates the discontinuity? (Crosscutting? Ambiguous cues?) If the shots are spatially continuous, how does the 180° system create the continuity?

- Are the shots temporally continuous? If so, what creates the continuity? (For example, matches on action?) If not, what creates the discontinuity? (Ellipsis? Overlapping cuts?)

More generally, we can ask the question we ask of every film technique: How does this technique

function

with respect to the film’s narrative form? Does the film use editing to lay out the narrative space, time, and cause–effect chain in the manner of classical continuity? How do editing patterns emphasize facial expressions, dialogue, or setting? Do editing patterns withhold narrative information? In general, how does editing contribute to the viewer’s experience of the film?

Some practical hints: You can learn to notice editing in several ways. If you are having trouble noticing cuts, try watching a film or TV show and tapping with a pencil each time a shot changes. Once you recognize editing easily, watch any film with the sole purpose of observing one editing aspect—say, the way space is presented or the control of graphics or time. Sensitize yourself to rhythmic editing by noting cutting rates; tapping out the tempo of the cuts can help.

Watching 1930s and 1940s American films can introduce you to classical continuity style; try to predict what shot will come next in a sequence. (You’ll be surprised at how often you’re right.) When you watch a film on video, try turning off the sound; editing patterns become more apparent this way. When there is a violation of continuity, ask yourself whether it is accidental or serves a purpose. When you see a film that does not obey classical continuity principles, search for its unique editing patterns. Use the slow-motion, freeze, and reverse controls on a DVD player to analyze a film sequence as this chapter has done. (Almost any film will do.) In such ways as these, you can considerably increase your awareness and understanding of the power of editing.

WHERE TO GO FROM HERE

Professional reflections on the work of the film editor include Ralph Rosenblum,

When the Shooting Stops … The Cutting Begins: A Film Editor’s Story

(New York: Penguin, 1980); Edward Dmytryk,

On Film Editing

(Boston: Focal Press, 1984); Vincent Lo Brutto,

Selected Takes: Film Editors on Film Editing

(New York: Praeger, 1991); Gabriella Oldham,

First Cut: Conversations with Film Editors

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992); and Declan McGrath,

Editing and Post-Production

(Hove, England: RotoVision, 2001). See also Ken Dancyger,

The Technique of Film and Video Editing: History, Theory, and Practice,

4th ed. (Boston: Focal Press, 2007), and “The Art and Craft of Film Editing,”

Cineaste

34, 2 (Spring 2009): 27–64.

Walter Murch, one of the most thoughtful and creative editors in history, provides a rich array of ideas in

In the Blink of an Eye: A Perspective on Film Editing,

2d ed. (Los Angeles: Silman-James, 2001). Murch, who worked on

American Graffiti, The Godfather, Apocalypse Now,

and

The English Patient,

has always conceived of image and sound editing as part of the same process. He shares his thoughts in an extended dialogue with prominent novelist Michael Ondaatje in

The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film

(New York: Knopf, 2002). Ever the experimenter, Murch tried using an inexpensive digital program to edit a theatrical feature. The result is traced in detail in Charles Koppelman,

Behind the Seen: How Walter Murch Edited

Cold Mountain

Using Apple’s Final Cut Pro and What This Means for Cinema

(Berkeley, CA: New Riders, 2005). You can listen to Murch discussing his work on the National Public Radio program

Fresh Air,

available at

www.npr.org

.

We await a large-scale history of editing, but André Bazin sketches a very influential account in “The Evolution of Film Language,” in

What Is Cinema?

vol. 1 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967),

pp. 23

–40. Editing in early U.S. cinema is carefully analyzed by Charlie Keil in

Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking, 1907–1913

(Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001). Professional editor Don Fairservice offers a thoughtful account of editing in the silent and early sound eras in

Film Editing: History, Theory and Practice

(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001). Several sections of Barry Salt’s

Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis

(London: Starword, 1992) are devoted to changes in editing practices.

Documentary films characteristically rely on editing, perhaps more than fictional films do. A set of cutting conventions has developed. For example, it is common to intercut talking-head shots of conflicting experts as a way of representing opposing points of view. Interestingly, in making

The Thin Blue Line,

Errol Morris instructed his editor, Paul Barnes, to avoid cutting between the two main suspects. “He didn’t want the standard documentary good guy/bad guy juxtaposition…. He hated when I intercut people telling the same story, or people contradicting or responding to what someone has just said” (Oldham,

First Cut,

p. 144

). Morris apparently wanted to give each speaker’s version a certain integrity, letting each stand as an alternative account of events.

Very little has been written on graphic aspects of editing. See Vladimir Nilsen,

The Cinema as a Graphic Art

(New York: Hill & Wang, 1959), and Jonas Mekas, “An Interview with Peter Kubelka,”

Film Culture

44 (Spring 1967): 42–47.

What we are calling rhythmic editing incorporates the categories of metric and rhythmic montage discussed by Sergei Eisenstein in “The Fourth Dimension in Cinema,” in

Selected Works,

vol. I,

pp. 181

–94. For a sample analysis of a film’s rhythm, see Lewis Jacobs, “D. W. Griffith,” in

The Rise of the American Film

(New York: Teachers College Press, 1968),

chap. 11

,

pp. 171

–201. Television commercials are useful to study for rhythmic editing, for their highly stereotyped imagery permits the editor to cut the shots to match the beat of the jingle on the sound track.

The Kuleshov experiments have been variously described. The two most authoritative accounts are in V. I. Pudovkin,

Film Technique

(New York: Grove Press, 1960), and Ronald Levaco, trans. and ed.,

Kuleshov on Film: Writings of Lev Kuleshov

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974),

pp. 51

–

55

. For a summary of Kuleshov’s work, see Vance Kepley, Jr., “The Kuleshov Workshop,”

Iris

4, 1 (1986): 5–23. Can the effect actually suggest an expressionless character’s emotional reaction? Two film researchers tried to test it, and their skeptical conclusions are set forth in Stephen Prince and Wayne E. Hensley, “The Kuleshov Effect: Recreating the Classic Experiment,”

Cinema Journal

31, 2 (Winter 1992): 59–75. During the 1990s, two Kuleshov experiments, one complete and one fragmentary, were discovered. For a description and historical background on one of them, see Yuri Tsivian, Ekaterina Khokhlova, and Kristin Thompson, “The Rediscovery of a Kuleshov Experiment: A Dossier,”

Film History

8, 3 (1996): 357–67.

For a historical discussion of continuity editing, see

Chapter 12

and the chapter’s bibliography. The hidden selectivity that continuity editing can achieve is well summarized in a remark from Thom Noble, who edited

Fahrenheit 451

and

Witness:

“What usually happens is that there are maybe seven moments in each scene that are brilliant. But they’re all on different takes. My job is to try and get all those seven moments in and yet have it look seamless, so that nobody knows there’s a cut in there” (quoted in David Chell, ed.,

Moviemakers at Work

[Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press, 1987],

pp. 81

–82).

Many sources spell out the rules of continuity. See Karel Reisz and Gavin Millar,

The Technique of Film Editing

(New York: Hastings House, 1973); Daniel Arijohn,

A Grammar of the Film Language

(New York: Focal Press, 1978); Edward Dmytryk,

On Screen Directing

(Boston: Focal Press, 1984); and Stuart Bass, “Editing Structures,” in

Transitions: Voices on the Craft of Digital Editing

(Birmingham, England: Friends of ED, 2002),

pp. 28

–

39

; and Richard D. Pepperman,

The Eye Is Quicker: Film Editing: Making a Good Film Better

(Los Angeles: Michael Wiese Productions, 2004). Our diagram of a hypothetical axis of action has been adapted from Edward Pincus’s concise discussion in his

Guide to Filmmaking

(New York: Signet, 1969),

pp. 120

–25.

For analyses of the continuity style, see Ramond Bellour, “The Obvious and the Code,”

Screen

15, 4 (Winter 1974–75): 7–17, and André Gaudreault, “Detours in Film Narrative: The Development of Cross-Cutting,”

Cinema Journal

19, 1 (Fall 1979): 35–59. Joyce E. Jesionowski presents a detailed study of Griffith’s distinctive version of early continuity editing in

Thinking in Pictures: Dramatic Structure in D. W. Griffith’s Biograph Films

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987). David Bordwell’s

Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000) considers how Hollywood continuity was used by another national cinema.

Professional editor Bobbie O’Steen analyzes sequences from 10 Hollywood classics shot by shot in

The Invisible Cut: How Editors Make Movie Magic

(Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions, 2009).

Taught in film schools and learned on the job by beginning filmmakers, the principles of continuity editing still dominate cinema around the world. As we suggested on

p. 250

, however, there have been some changes in the system. Shots tend to be shorter (

Moulin Rouge

contains over 4000) and framed closer to the performers. The medium shots in older filmmaking traditions display the hands and upper body fully, but intensified continuity concentrates on faces, particularly the actor’s eyes. Film editor Walter Murch says, “The determining factor for selecting a particular shot is frequently: ‘Can you register the expression in the actor’s eyes?’ If you can’t, the editor will tend to use the next closer shot, even though the wider shot may be more than adequate when seen on the big screen.”

There’s some evidence that today’s faster cutting pace and frequent camera movements allow directors to be a bit loose in matching eyelines. In several scenes of

Hulk, Mystic River, 8 Mile,

and

Syriana,

the axis of action is crossed, sometimes repeatedly. If viewers aren’t confused by these cuts, it’s perhaps because the actors don’t move around the set very much and so the overall spatial layout remains clear. More complex spatial layouts may require more cutaways and sound cues, as editor Alan Heim explains with respect to one scene in

The Notebook.

See the Editors Guild website at

www.editorsguild.com/v2/magazine/Newsletter/JulAug04/julaug04_notebook.html

.

For more on intensified continuity, see David Bordwell,

The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006),

pp. 117

–89.

Eisenstein remains the chief source in this area. A highly introspective filmmaker, he bequeathed us a rich set of ideas on the possibilities of non-narrative editing; see the essays in

Selected Works,

vol. 1. For further discussion of editing in

October,

see the essays by Annette Michelson, Noël Carroll, and Rosalind Krauss in the special “Eisenstein/Brakhage” issue of

Artforum

11, 5 (January 1973): 30–37, 56–65. For a more general view of Eisenstein’s editing, see David Bordwell,

The Cinema of Eisenstein

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993). The writings of another Russian, Dziga Vertov, are also of interest. See Annette Michelson, ed.,

Kino-Eye: The Writings of Dziga Vertov

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984). On Ozu’s manipulation of discontinuities, see David Bordwell,

Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988).

www.editorsguild.com/v2/index.aspx/

A website supporting

Editors Guild

magazine, with many articles and interviews discussing editing in current films.

www.uemedia.com/CPC/editorsnet/

Offers articles on contemporary problems of editing.

Recommended DVD Supplementswww.cinemetrics.lv/

Want to study cutting rhythms in a movie of your choice? This nifty software allows you to come up with a profile of editing rates.

Watching people editing is not very exciting, and this technique usually gets short shrift in DVD supplements. Each film in the

Lord of the Rings

trilogy, however, has an “Editorial” section, and

The Fellowship of the Ring

includes an “Editorial Demonstration,” juxtaposing the raw footage from six cameras in an excerpt from the Council of Elrond scene and showing how sections from each were fitted together. (An instructive exercise in learning to notice continuity editing would be to watch the Council of Elrond scene in the film itself with the sound turned off. Here a complex scene with many characters is stitched together with numerous correct eyeline matches and occasional matches on action. Imagine how confusing the characters’ conversations could have been if no attention had been paid to eyeline direction.)

The DVD release of Lodge Kerrigan’s

Keane

includes not only the theatrical version but a completely recut version of the film by producer Steven Soderberg. Soderberg calls his cut his “commentary track” for the disc.

In “Tell Us What You See,” the camera operator for

A Hard Day’s Night

discusses continuity of screen direction, and in “Every Head She’s Had the Pleasure to Know,” the film’s hairdresser talks about having to keep hair length consistent for continuity.

“15-Minute Film School with Robert Rodriguez,” one of the

Sin City

supplements, provides a clear instance of the Kuleshov effect in use. Although Rodriguez does not use that term, he demonstrates how he could cut together shots of characters interacting with each other via eyeline matches even though several of the actors never worked together during the filming.

A brief section of

Toy Story

’s supplements entitled “Layout Tricks” demonstrates how continuity editing principles are adhered to in animation as well as live-action filming. In a shot/reverse-shot sequence involving Buzz and Woody, the filmmakers diagram (as we do on

p. 238

) where a camera can be placed to maintain the axis of action (or “stage line,” as it is termed here). The segment also shows how a camera movement can be used to shift the axis of action just before an important character enters the scene.

“Destination Yuma,” a short making-of for

3:10 to Yuma,

contains an excellent demonstration of multiple-camera shooting for a scene of a stagecoach flipping over; the shooting and views from different cameras are immediately followed by the scene as edited in the final film. The audio commentary for

El Mariachi

(Sony “Special Edition”) describes editing scenes using the Kuleshov effect.