B0041VYHGW EBOK (147 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

So far the film has seemed to follow its initial purpose of telling a story of the river. But in

segment 4

, it begins to introduce the problems that the TVA will eventually solve. The film shows the results of the Civil War: destroyed houses and dispossessed landowners, the land worn out by the cultivation of cotton, and people forced to move west. The moral tone of the film becomes apparent, and it is an appealing one. Over images of impoverished people, somber music plays. It is based on a familiar folk tune, “Go Tell Aunt Rhody,” which, with its line “The old gray goose is dead” underscores the losses of the farmers. The narrator’s voice expresses compassion as he speaks of the South’s “tragedy of land impoverished.” This attitude of sympathy may incline us to accept as true other things that the film tells us. The narrator also refers to the people of the period as “we”: “We mined the soil for cotton until it would yield no more.” Here the film’s persuasive intent becomes evident. It was not literally

we

—you and I and the narrator—who grew this cotton. The use of

we

is a rhetorical strategy to make us feel that all Americans share a responsibility for this problem and for finding a solution.

Later segments repeat the strategies of these earlier ones. In segment 5, the film again uses poetically repetitious narration to describe the lumber industry’s growth after the Civil War, listing “black spruce and Norway pine” and other trees. In the images, we see evergreens against the sky, echoing the cloud motif that opened

segments 2

and

3

(

10.32

).

This creates a parallel between the riches of the agricultural and the industrial areas. A sprightly sequence of logging, accompanied by music based on the tune “Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight,” again gives us a sense of America’s vigor. A section on coal mining and steel mills follows, enhancing this impression. This segment ends with references to the growing urban centers: “We built a hundred cities and a thousand towns,” and we hear a list of some of their names.

10.32 Motifs of pines and clouds in

The River.

Up to this point, we have seen the strengths of America associated with the river valley, with just a hint of problems that growth has sparked. But segment 6 switches tracks and creates a lengthy series of contrasts to the earlier parts. It begins with the same list of trees—“black spruce and Norway pine”—but now we see stumps against fog instead of trees against clouds

(

10.33

).

Another line returns, but with a new phrase added: “We built a hundred cities and a thousand towns … but at what a cost.” Beginning with the barren hilltops, we are shown how melting ice runs off, and how the runoff gradually erodes hillsides and swells rivers into flooding torrents. Once more we hear the list of rivers from

segment 2

, but now the music is somber and the rivers are no longer idyllic. Again there is a parallel presented between the soil erosion here and the soil depletion in the South after the Civil War.

10.33 The pines now transformed into stumps, the clouds into fog.

It’s worth pausing to comment on Lorentz’s use of film style here, for he reinforces the film’s argument through techniques that arouse the audience’s emotions. The contrast of segment 6 with the lively logging segment that precedes it could hardly be stronger. The sequence begins with lingering shots of the fog-shrouded stumps (

10.33

). There is little movement. The music consists of threatening, pulsing chords. The narrator speaks more deliberately. Dissolves, rather than straight cuts, connect the shots. The segment slowly builds up tension. One shot shows a stump draped with icicles, and an abrupt cut-in emphasizes the steady drip from them

(

10.34

).

A sudden, highly dissonant chord signals us to expect danger.

10.34 In

The River,

shots of icicles dripping lead to a segment on erosion.

Then, in a series of close-ups of the earth, water gathers, first in trickles

(

10.35

),

then in streams washing the soil away. By now the music is very rhythmic, with soft, tom-tom-like beats punctuating a plaintive and rising orchestral melody. The narrator begins supplying dates, each time more urgently insistent: “Nineteen-seven”

(

10.36

),

“Nineteen-thirteen”

(

10.37

),

“Nineteen-sixteen”

(

10.38

),

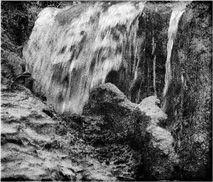

and on up to 1937. With each date, we see streams turning into creeks, and creeks into waterfalls, and eventually rivers overflowing their banks.

10.35

The River.

10.36

The River.

10.37

The River.

10.38

The River.

As the flooding intensifies, brief shots of lightning bolts are intercut with shots of raging water. The dramatic music is overwhelmed by sirens and whistles. From a situation of natural beauty, the film has taken us to a disaster for which humans were responsible. Lorentz’s stylistic choices have blended to convey a sense of rising tension, convincing us of the flood’s threat. Were we not to grasp that threat emotionally as well as factually, the film’s overall argument would be less compelling. Throughout

The River,

voice, music, editing, and movement within the shot combine to create a rhythm for such rhetorical purposes.

By this point, we understand the information the film is presenting about flooding and erosion. Still, the film witholds the solution and presents the effects of the floods on people’s lives in contemporary America. Segment 7 describes government aid to flood victims in 1937 but points out that the basic problem still exists. The narrator employs a striking enthymeme here: “And poor land makes poor people—poor people make poor land.” This sounds reasonable on the surface, but upon examination, its meaning becomes unclear. Didn’t the rich southern plantation owners whose ruined mansions we saw in

segment 4

have a lot to do with the impoverishment of the soil? Such statements are employed more for their poetic neatness and emotional appeal than for any rigorous reasoning they may contain. Scenes of tenant farmer families

(

10.39

)

appeal directly to our emotional response to such poverty. This segment picks up on motifs introduced in

segment 4

, on the Civil War. Now, the film tells us, these people cannot go west, because there is no more open land there.

10.39

The River.