B0041VYHGW EBOK (158 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

10.100

Toy Story

’s computer-generated world.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

We comment on the Oscar-nominated shorts for 2007 in “Do sell us shorts,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=1930

, and the ones for 2008 in “Do sell us shorts, the sequel,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=3567

.

Computer animation can also be used to simulate the look of traditional cel animation. Working on a computer can make the processes of painting colors onto the cel or of joining the various layers of the image more efficient and consistent. For example, Japan’s master cel animator Hayao Miyazaki adopted computer techniques for some images of his 1997 film

Princess Mononoke.

Miyazaki used morphing, multilayer compositing, and painting for about 100 of the film’s total of around 1600 shots

(

10.101

),

yet the difference from traditional cel animation is virtually undetectable on the screen. (For more on Japanese animation, or

anime,

see

“Where to Go from Here.”

)

10.101 In

Princess Mononoke,

five portions of the image (the grass and forest, the path and motion lines, the body of the Demon God, the shading of the Demon God, and Ashitaka riding away) were joined by computer, giving smoother, more complex motions than regular cel animation could achieve.

In 1989, James Cameron’s thriller

The Abyss

popularized computer animation in live-action features by creating a shimmering water creature. Since then, computer animation has created dinosaurs for

Jurassic Park

(

1.29

), and the realistic, humanlike creature Gollum in

The Lord of the Rings.

(For a discussion of computer-generated special effects in live-action films, see

pp. 30

–32.)

Animation is sometimes mixed with live-action filming. Walt Disney’s earliest success in the 1920s came with a series, “Alice in Cartoonland,” which placed a little girl played by an actress in a black-and-white drawn world. Gene Kelly entered a world of cels to dance with Jerry the Mouse in

Anchors Aweigh.

Perhaps the most elaborate combination of cel animation and live action has been

Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

(

5.52

).

“As the six-year-old boy protested when I was introduced to him as the man who draws Bugs Bunny, ‘He does not! He draws pictures

of

Bugs Bunny.’”— Chuck Jones, animator

“Animators have only one thing in common. We are all control freaks. And what is more controllable than the inanimate? You can control every frame, but at a cost. The cost is the chunks of your life that the time-consuming process devours. It is as if the objects suck your time and energy away to feed their own life.”

— Simon Pummell, animator

Duck Amuck

During the golden age of Hollywood short cartoons, from the 1930s to the 1950s, Disney and Warner Bros. were rivals. Disney animators had far greater resources at their disposal, and their animation was more elaborate and detailed than the simpler style of the Warner product. Warner cartoonists, despite their limited budgets, fought back by exploiting the comic fantasy possible in animated films and playing with the medium in imaginative ways.

In Warner Bros. cartoons, characters often spoke to the audience or referred to the animators and studio executives. For example, the Warner unit’s producer Leon Schlesinger appeared in

You Ought to Be in Pictures,

letting Porky Pig out of his contract so that he could try to move up to live-action features. The tone of the Warner cartoons distinguished them sharply from the Disney product. The action was faster and more violent. The main characters, such as Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, were wisecracking cynics rather than innocent altruists like Mickey Mouse.

The Warner animators tried many experiments over the years, but perhaps none was so extreme as

Duck Amuck,

directed by Charles M. (Chuck) Jones in 1953. It is now recognized as one of the masterpieces of American animation. Although it was made within the Hollywood system and uses narrative form, it has an experimental feel because it asks the audience to take part in an exploration of techniques of cel animation.

As the film begins, it seems to be a swashbuckler of the sort Daffy Duck had appeared in before, such as

The Scarlet Pumpernickel

(1950)—itself a parody of one of Errol Flynn’s most famous Warner Bros. films. The credits are written on a scroll fastened to a wooden door with a dagger, and when Daffy is first seen, he appears to be a dueling musketeer. But almost immediately he moves to the left and passes the edge of the painted background

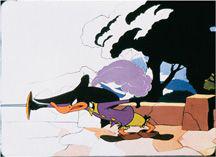

(

10.102

).

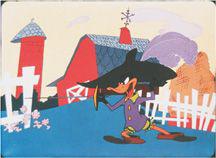

Daffy is baffled, calls for scenery, and exits. A giant animated brush appears from outside the frame and paints in a barnyard

(

10.103

).

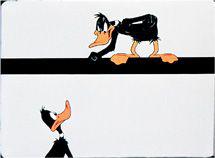

When Daffy enters, still in musketeer costume, he is annoyed but changes into a farmer’s outfit. Such quick switches continue throughout the film, with the paintbrush and a pencil eraser adding and removing scenery, costumes, props, and even Daffy himself, with dizzying illogic. At times the sound cuts out, or the film seems to slip in the projector, so that we see the frame line in the middle of the screen

(

10.104

).

10.102 Early in

Duck Amuck,

the background tapers off into white blankness.

10.103 An inappropriate background for a swashbuckler appears in the blank space.

10.104 In

Duck Amuck,

as the image apparently slips in the projector, Daffy’s feet appear at the top and his head at the bottom.

All these tricks result in a peculiar narrative. Daffy repeatedly tries to get a plot, any plot, going, and the unseen animator constantly thwarts him. As a result, the film’s principles of narrative progression are unusual. First, it gradually becomes apparent to us that the film is exploring various conventions and techniques of animation: painted backgrounds, sound effects, framing, music, and so on. Second, the outrages perpetrated against Daffy become more extreme, and his frustration mounts steadily. Third, a mystery quickly surfaces, as we and Daffy wonder who this perverse animator is and why he is tormenting Daffy.

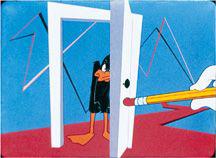

At the end, the mystery is solved when the animator blasts Daffy with a bomb and then closes a door in his face

(

10.105

).

The next shot moves us to the animation desk itself, where we see Bugs Bunny, who has been the animator playing all the tricks on Daffy. He grins at us: “Ain’t I a stinker?”

(

10.106

).

To a spectator who has never seen a Warner Bros. cartoon before, this ending would be puzzling. The narrative logic of

Duck Amuck

depends largely on knowing the character traits of the two stars. Bugs and Daffy often costarred in other Jones cartoons, and invariably the calm, ruthless Bugs would get the better of the manic Daffy.

10.105 A pencil protruding into the frame finally begins to reveal

Duck Amuck

’s fiendish animator.

10.106 As in many other Warner Bros. cartoons, Bugs turns and speaks to the audience after he triumphs over Daffy.