B0041VYHGW EBOK (191 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Eisenstein’s first feature,

Strike,

was released early in 1925 and initiated the movement proper. His second,

Potemkin,

premiered later in 1925, was successful abroad and drew the attention of other countries to the new movement. In the next few years, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Vertov, and the Ukrainian Alexander Dovzhenko created a series of films that are classics of the Montage style.

In their writings and films, these directors championed the powers of editing. Until the late 1910s, most Russian fiction films had based their scenes around lengthy, fairly distant shots that captured the actors’ performances. Analytical editing was rare. But films from Hollywood and from the French Impressionist filmmakers told their stories through fast cutting, including frequent close framings. Inspired by these imports, the young Soviet directors declared that a film’s power arose from the combination of shots. Montage seemed to be the way forward for modern cinema.

Not all of the young theoreticians agreed on exactly what the Montage approach to editing should be. Pudovkin, for example, believed that shots were like bricks, to be joined together to build a sequence. Eisenstein disagreed, saying that the maximum effect would be gained if the shots did not fit together perfectly, if they created a jolt for the spectator. Many filmmakers in the montage movement followed this approach

(

12.30

).

Eisenstein also favored juxtaposing shots in order to create a concept, as we have already seen with his use of conceptual editing in

October

(

pp. 422

–425). Vertov disagreed with both theorists, favoring a cinemaeye approach to recording and shaping documentary reality (

pp. 257

–260).

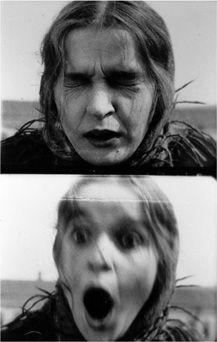

12.30 In

House on Trubnoi Square,

Montage director Boris Barnet uses a jump cut to convey the heroine’s sudden realization that a streetcar is headed straight for her.

Pudovkin’s

Storm over Asia

makes use of conceptual editing similar to that of Eisenstein’s

October.

Shots of a military officer and his wife being dressed in their accessories are intercut with shots of the preparation at the temple

(

12.31

–

12.34

).

Pudovkin’s parallel montage points up the absurdity of both rituals.

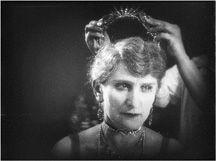

12.31 In

Storm over Asia,

after a medium close-up of an elaborate piece of jewelry being lowered over the head of a priest, there is a cut …

12.32 … to a close-up of a servant placing a necklace around the neck of the officer’s wife …

12.33 … then a cut back to a large headdress being positioned on a priest’s head …

12.34 … juxtaposed with a close-up of a tiara being set on the wife’s head.

The Montagists’ approach to narrative form set them apart from the cinemas of other countries. Soviet narrative films tended to downplay character psychology as a cause; instead, social forces provided the major causes. Characters were interesting for the way these social causes affected their lives. As a result, films of the Soviet Montage movement did not always have a single protagonist. Social groups could form a collective hero, as in several of Eisenstein’s films. In keeping with this downplaying of individual personalities, Soviet filmmakers often avoided well-known actors, preferring to cast parts by searching out nonactors. This practice was called

typage

, since the filmmakers would often choose an individual whose appearance seemed at once to convey the type of character he or she was to play. Except for the hero, Pudovkin used nonactors to play all of the Mongols in

Storm over Asia.

By the end of the 1920s, each of the major directors of this movement had made about four important films. The decline of the movement was not caused primarily by industrial and economic factors as in Germany and France. Instead, the government strongly discouraged the Montage style. By the late 1920s, Vertov, Eisenstein, and Dovzhenko were being criticized for their excessively formal and esoteric approaches. In 1929, Eisenstein went to Hollywood to study the new technique of sound; by the time he returned in 1932, the attitude of the film industry had changed. While he was away, a few filmmakers carried their Montage experiments into sound cinema in the early 1930s. But the Soviet authorities, under Stalin’s direction, encouraged filmmakers to create simple films that would be readily understandable to all audiences. Stylistic experimentation or nonrealistic subject matter was often criticized or censored.

This trend culminated in 1934, when the government instituted a new artistic policy called Socialist Realism. This policy dictated that all artworks must depict revolutionary development while being firmly grounded in realism. The great Soviet directors continued to make films, occasionally masterpieces, but the Montage experiments of the 1920s had to be discarded or modified. Eisenstein managed to continue his work on Montage but occasionally incurred the wrath of the authorities up until his death in 1948. As a movement, the Soviet Montage style can be said to have ended by 1933, with the release of such films as Vertov’s

Enthusiasm

(1931) and Pudovkin’s

Deserter

(1933).

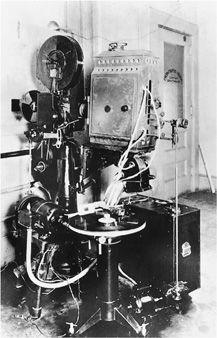

The introduction of sound technology came about through the efforts of Hollywood firms to widen their power. During the mid-1920s, Warner Bros. was expanding its facilities and holdings. One of these expansions was the investment in a sound system using records in synchronization with film images

(

12.35

).

12.35 An early projector with a turntable (lower center) attached.

By releasing

Don Juan

(1926) with orchestral accompaniment and sound effects on disc, along with a series of vaudeville shorts with singing and talking, Warner Bros. began to popularize the idea of sound films. In 1927,

The Jazz Singer

(a part-talkie with some scenes accompanied only by music) was a tremendous success, and the Warner Bros. investment began to pay off.

The success of

Don Juan, The Jazz Singer,

and the shorts convinced other studios that sound contributed to profitable filmmaking. Unlike the early period of filmmaking and the Motion Picture Patents Company, there was now no fierce competition within the industry. Instead, firms realized that whatever sound system the studios finally adopted, it would have to be compatible with the projection machinery of any theater. Eventually, a sound-on-film rather than a sound-on-disc system became the standard and continues so to the present. (That is, as we saw in

Chapter 1

, the sound track is printed on the strip of film alongside the image.) By 1930, most theaters in America were wired for sound.

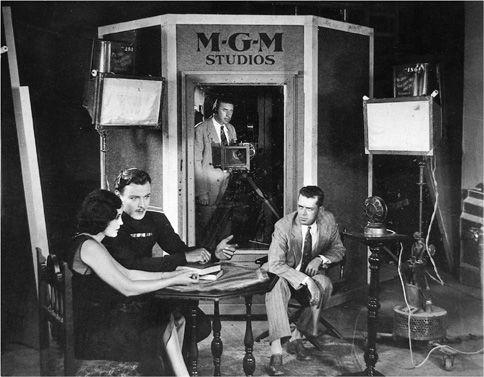

For a few years, sound created a setback for Hollywood film style. The camera had to be put inside a sound booth so that its motor noise would not be picked up by the microphone. The components of a dialogue scene in a 1928 MGM film can be seen in

12.36

. The camera operator could hear only through his earphones, and the camera could not move except for short pans to reframe. The bulky microphone, on the table at the right, also did not move. The actors had to stay within a limited space if their speech was to register on the track. The result of such restrictions was a brief period of static films resembling stage plays.

12.36 A posed publicity still demonstrated the limitations of early sound filming.