B0041VYHGW EBOK (178 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

“I don’t shoot elegant pictures. Mr. Vincente Minnelli,

he

shot elegant pictures.”— Billy Wilder, director

All of the films we have analyzed could be examined for their ideological standpoints. Any film combines formal and stylistic elements in such a way as to create an ideological stance, whether overtly stated or tacit. We’ve chosen to stress the ideology of

Meet Me in St. Louis

because it provides a clear example of a film that doesn’t seek to change people’s ways of thinking. Instead, it tends to reinforce certain aspects of a dominant social ideology. In this case,

Meet Me in St. Louis,

like most Hollywood films, seeks to uphold what are conceived as characteristically American values of family unity and home life.

Meet Me in St. Louis

is set during the preparations for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, with the fair itself becoming the culmination of the action. The film displays its form in a straightforward way, with a title card announcing each of its four sections with a different season

(

11.91

).

In this way, the film simultaneously suggests the passage of time (equated with a movement toward the spring 1904 fair, which will bring the fruits of progress to St. Louis) and the unchanging cycle of the seasons.

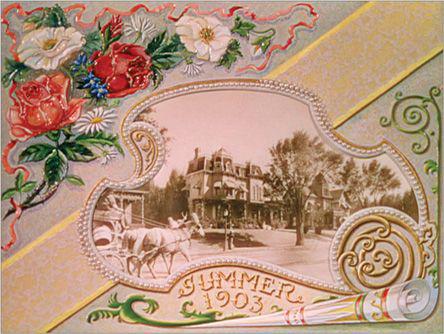

11.91 The opening title card, “Summer 1903,” in

Meet Me in St. Louis.

The Smiths, living in a big Victorian house, form a large but close-knit family. The seasonal structure allows the film to show the Smiths at the traditional times of family unity, the holidays; we see them celebrating Halloween and Christmas. At the end, the fair becomes a new sort of holiday, the celebration of the Smiths’ decision to remain in St. Louis.

The opening of the film quickly introduces the idea of St. Louis as a city on the boundary between tradition and progress. The fancy candy-box title card for summer forms a vignette of white and red flowers around an old-fashioned black-and-white photo of the Smiths’ house. As the camera moves in, color fades into the photo, and it comes to life

(

11.92

).

Slow, subdued chords over the title card give way to a bouncy tune more in keeping with the onscreen movement. Horse-drawn beer wagons and carriages move along the road, but an early-model automobile (a bright red, which draws our eye) passes them. Already the motif of progress and inventions becomes prominent; it will develop quickly into the emphasis on the upcoming fair.

11.92 The transition into the world of 1903 St. Louis.

As Lon Smith, the son, arrives home by bicycle, a dissolve inside to the kitchen launches the exposition. One by one we meet the family members as they go about their daily activities through the house. The camera follows the second youngest daughter, Agnes, as she goes upstairs singing “Meet Me in St. Louis”

(

11.93

).

She encounters Grandpa, who takes up the song as the camera follows him briefly. By means of close matches on action on the characters’ passing the song along, the image track yields a flow of movement that presents the house as full of bustle and music. Grandpa hears offscreen voices singing the same song. He moves to a window, and a high-angle shot from over his shoulder shows the second oldest sister, Esther, stepping out of a buggy

(

11.94

).

Her arrival brings the sequence full circle back to the front of the house.

11.93 The song “Meet Me in St. Louis” introduces us to the characters and locations.

11.94 The importance of the family house: A window frames our first view of the heroine …

The house remains the main image of family unity throughout most of the film. Aside from the expedition of the young people on the trolley to see the construction of the fair, the Christmas dance, and the final fairground sequence, the entire action of the film takes place in or near the Smith house. Although Mr. Smith’s job provides the reason to move to New York, we never see him at his office. In the opening sequence, the family members return home one by one, until they all gather around the dinner table. Every seasonal section of the film begins with a similar candy-box title card and a move in toward the house. In the film’s ideology, the home appears to be a self-sufficient place; other social institutions become peripheral, even threatening.

This vision of the unified family within an idealized household places the women at the center. The narration does not restrict our knowledge to a single character’s range, but it tends to concentrate on what the Smith women know. Mrs. Smith, the oldest daughter Rose, the youngest daughter Tootie, and in particular Esther are the characters around which the narration is organized. Moreover, women are portrayed as the agents of stability. The action in the story constantly returns to the kitchen, where Mrs. Smith and the maid, Katie, work calmly in the midst of small crises. The men present the threat to the family’s unity. Mr. Smith wants to take the family to New York, thereby destroying its ties with the past. Lon goes away to the East, to college at Princeton. Only Grandpa, as representative of the older generation, sides with the women in their desire to stay in St. Louis. In general, the narrative’s causality makes any departure from the home problematic—an example of how a narrative’s principles of development can generate an ideological premise.

Within the family, there are minor disagreements, but the members cooperate. The two older sisters, Rose and Esther, help each other in their flirtations. Esther is in love with the boy next door, John Truitt, and marriage to him poses no threat to the family unity. Several times in the film, she gazes across at his house without having to leave her own home. First, she and Rose go out onto the porch to try to attract his attention; then she sits in the window to sing “The Boy Next Door”

(

11.95

).

Finally, much later, she sits in a darkened bedroom upstairs and sees John pull his shade just after they have become engaged. That the girls might want to travel, or to educate themselves beyond high school, is never considered. By concentrating on the round of small incidents in the household and neighborhood, the film blocks consideration of any alternative way of living—except the dreaded move to New York.

11.95 … and later her song, “The Boy Next Door.”

Many stylistic devices build up a picture of a happy family life. The Technicolor design contributes greatly to the lushness of the mise-en-scene, making the costumes, the surroundings, and the characters’ hair color stand out richly (5.5). The characters wear bright clothes, with Esther often in blue. She and Rose wear red and green, to the Christmas dance

(

11.96

).

This strengthens the association of the family unity with holidays and incidentally makes the sisters easy to pick out in the swirling crowd of pastel-clad dancers. In 5.5, the shot from the trolley scene, Esther is conspicuous because she is the only woman in black amidst the generally bright-colored dresses.

11.96 Christmas party gowns form part of the film’s holidays motif.

Meet Me in St. Louis

is a musical, and music plays a large part in the family’s life. Songs come at moments of romance or gathering. Rose and Esther sing “Meet Me in St. Louis” in the parlor before dinner. When Mr. Smith interrupts them on returning from work—”For heaven’s sake, stop that screeching!”—he is immediately characterized as opposed to the singing and to the fair. Esther’s other songs show that her romance with John Truitt is a safe and reasonable one. A woman does not have to leave home to find a husband: she can find him right in her own neighborhood (“The Boy Next Door”) or by riding the trolley (“The Trolley Song”). Other songs accompany the two parties, and Esther sings “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” to Tootie, the youngest sister, after the Christmas dance. Here she tries to reassure Tootie that life in New York will be all right if the family can remain together.