B0041VYHGW EBOK (174 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Since the lines of action in the two parts aren’t linked causally, the film may at first disappoint the viewer’s expectations. But Wong’s strategy invites the audience to seek other connections. The parallel situations point to the idea that change is as necessary to love as variety is to diet. The thematic implications are reinforced by mise-en-scene, cinematography, music, and voice-over commentary. Yet

Chungking Express

isn’t heavy-handed, partly because it slides cleverly from crime movie to stop-and-start romance and partly because it invites us to appreciate its playful artifice.

Man with a Movie Camera (Chelovek s kinoapparatom)

Made 1928, released 1929. VUFKU, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Directed by Dziga Vertov. Photographed by Mikhail Kaufman. Edited by Elizaveta Svilova.

In some ways,

Man with a Movie Camera

might seem to be a straight reportorial documentary, yet it does not try to give the impression that the reality it presents is unaffected by the medium of film. Instead, Dziga Vertov proclaims the manipulative power of editing and cinematography to shape a multitude of tiny scenes from everyday reality into a highly idiosyncratic, even somewhat experimental, documentary.

Vertov’s name is usually linked to the technique of editing; in

Chapter 6

(

p. 277

), we quoted a passage in which he equated the filmmaker with an eye, gathering shots from many places and linking them creatively for the spectator. Vertov’s theoretical writings also compare the eye to the lens of the camera, in a concept he termed the “kino eye.” (

Kino

is the Russian word for “cinema,” and one of his earlier films is called

Kino-Glaz,

or

Cinema-Eye.

)

Man with a Movie Camera

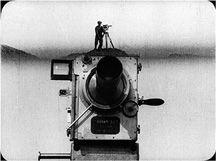

takes this idea—the equation of the filmmaker’s eye with the lens of the camera—as the basis for the entire film’s associational form. The film becomes a celebration of the documentary filmmaker’s power to control our perception of reality by means of editing and special effects. The opening image shows a camera in close-up. Through a double-exposure effect, we see the cameraman of the film’s title suddenly climb, in extreme long shot, onto the top of the giant camera

(

11.72

).

He sets up his own camera on a tripod and films for a bit, then climbs down again. This play on shot scale within a single image emphasizes at once the power the cinema has to alter reality in a seemingly magical way.

11.72 Vertov’s regular cinematographer, Mikhail Kaufman, as the cameraman in

Man with a Movie Camera.

Cinematographic special effects of this sort appear as a motif throughout the film. These are not intended to be unnoticeable, as in a science-fiction film. Instead, they flaunt the fact that the camera can alter everyday reality. A typical example is shown in

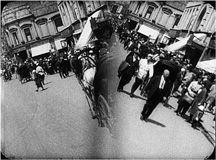

11.73

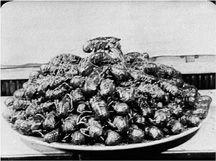

. Later Vertov uses pixillation to animate objects

(

11.74

).

In another scene, he conveys the sound of a radio by superimposing images of a dancer and of a hand playing a piano against a single black background

(

11.75

).

This motif of virtuosic special effects culminates in the famous final shot

(

11.76

).

11.73 Vertov alters an ordinary street scene by exposing each side of the image separately, with the camera canted in opposite directions.

11.74 A crayfish executes a little dance in the course of this shot.

11.75 Superimposition to suggest sound.

11.76

Man with a Movie Camera

ends with an eye superimposed over the camera lens, staring straight out at us.

At several points in the film, the camera is also personified, associated by editing with the actions of human beings. One brief segment shows the camera lens focusing and then a blurry shot of flowers coming into sharp focus. This is followed immediately by a comic juxtaposition rapidly intercutting two elements: a woman’s fluttering eyelids as she dries her face with a towel, and a set of venetian blinds opening and closing. Finally, another shot shows the camera lens with a diaphragm closing and opening. A human eye is like venetian blinds, the lens is like an eye—all can open and close, admitting or keeping out light. Later, pixillation allows the camera to move by itself

(

11.77

)

and finally then to walk off on three legs.

11.77 The animated camera comes out of its box, climbs onto the tripod, and demonstrates how its various parts work.

Man with a Movie Camera

belongs to a genre of documentaries that first became important during the 1920s: the

city symphony.

There are many ways of making a film about a city, of course. One might use categorical form to lay out its geography or scenic attractions, as in a travelogue. Rhetorical form could make arguments about aspects of city planning or government policies that need changing. A narrative might stress a city as the backdrop for many characters’ actions, as in Rossellini’s

Rome Open City

or Jules Dassin’s semidocumentary crime drama

The Naked City.

Early city symphonies, however, established the convention of taking candid (or occasionally staged) scenes of city life and linking them, usually without commentary, through associations to suggest emotions or concepts. Associational form is evident in such early examples of the genre as Alberto Cavalcanti’s

Rien que les heures

(1926) and Walter Ruttmann’s

Berlin, Symphony of a Great City

(1927). More recent films like Godfrey Reggio’s

Koyaanisqatsi

(1983) and

Powaqqatsi

(1988) use similar techniques, avoiding voice-over narration in favor of a musical accompaniment that along with juxtapositions of images creates particular moods and evokes certain concepts. (See

pp. 172

–175.)

In

Man with a Movie Camera

’s opening, we see a camera operator filming, then passing between the curtains of an empty movie theater and moving toward the screen. Then we see the theater opening, the spectators filing in, the orchestra preparing to play, and the film commencing. The film that we and the audience watch seems at first to be a city symphony laying out a typical day in the life of a town (as Ruttmann’s

Berlin

does). We see a woman asleep, mannequins in closed shops, and empty streets. Soon a few people appear, and the city wakes up. Indeed, much of

Man with a Movie Camera

follows a rough principle of development that progresses from waking up through work time to leisure time. But early in the wakingup portion, we also see the cameraman again, setting out with his equipment, as if starting his workday. This action creates the first of many deliberate inconsistencies. The cameraman now appears in his own film, and Vertov emphasizes this by cutting back immediately to the sleeping woman who had been the first thing we saw in the film-within-a-film.

Throughout

Man with a Movie Camera,

we see the same actions and shots being filmed, edited, and viewed, in scrambled order, by the onscreen audience. Toward the end of the film, in fact, we see the audience in the theater watching the cameraman on the screen, filming from a moving motorcycle. Moreover, in this late portion of the film, many motifs from all the earlier parts of the day return, many now in fast motion; the simple order of the ordinary city symphony is broken and jumbled. Vertov creates an impossible time scheme, once more emphasizing the extraordinary manipulative powers of the cinema. The film also refuses to show only one city, instead mixing footage filmed in Moscow, Kiev, and Odessa, as if the cameraman hero can move effortlessly across the USSR during this “day” of filming. Vertov’s view of the cinema’s relation to the cityscape is well conveyed in one shot that uses an extraordinary deep-focus composition to place the camera in the foreground, looming over the distant buildings

(

11.78

).

In sum,

Man with a Movie Camera

is a city symphony, but it goes beyond the genre as well.