B0041VYHGW EBOK (28 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

2.15 Through her crystal ball, the Wicked Witch mocks Dorothy.

Differences among the elements may often sharpen into downright opposition among them. We’re most familiar with formal oppositions as clashes among characters. In

The Wizard of Oz,

Dorothy’s desires are opposed, at various points, by the differing desires of Aunt Em, Miss Gulch, the Wicked Witch, and the Wizard, so that our experience of the film is engaged through dramatic conflict. But character conflict isn’t the only way the formal principle of difference may manifest itself. Settings, actions, and other elements may be opposed.

The Wizard of Oz

presents color oppositions: black-and-white Kansas versus colorful Oz; Dorothy in red, white, and blue versus the Witch in black. Settings are opposed as well—not only Oz versus Kansas but also the various locales within Oz

(

2.16

,

2.17

).

Voice quality, musical tunes, and a host of other elements play off against one another, demonstrating that any motif may be opposed by any other motif.

2.16 Centered in the upper half of the frame, the Emerald City creates a striking contrast to …

2.17 … the similar composition showing the castle of the Wicked Witch of the West.

Not all differences are simple oppositions, of course. Dorothy’s three Oz friends—the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, and the Lion—are distinguished not only by external features but also by means of a three-term comparison of what they lack (a brain, a heart, courage). Other films may rely on less sharp differences, suggesting a scale of gradations among the characters, as in Jean Renoir’s

The Rules of the Game.

At the extreme, an abstract film may create minimal variations among its parts, such as in the slight changes that accompany each return of the same footage in J. J. Murphy’s

Print Generation

(p. 000).

Repetition and variation are two sides of the same coin. To notice one is to notice the other. In thinking about films, we ought to look for similarities

and

differences. Shuttling between the two, we can point out motifs and contrast the changes they undergo, recognize parallelisms as repetition, and still spot crucial variations.

One way to keep ourselves aware of how similarity and difference operate in film form is to look for principles of development from part to part. Development constitutes some patterning of similar and differing elements. Our pattern ABACA is based not only on repetition (the recurring motif of A) and difference (the insertion of B and C) but also on a principle of

progression

that we could state as a rule: alternate A with successive letters in alphabetical order. Though simple, this is a principle of

development,

governing the form of the whole series.

Think of formal development as

a progression moving from beginning through middle to end.

The story of

The Wizard of Oz

shows development in many ways. It is, for one thing, a

journey:

from Kansas through Oz to Kansas. The good witch Glinda emphasizes this formal pattern by telling Dorothy that “It’s always best to start at the beginning”

(

2.18

).

Many films possess such a journey plot.

The Wizard of Oz

is also a

search,

beginning with an initial separation from home, tracing a series of efforts to find a way home, and ending with home being found. Within the film, there is also a pattern of

mystery,

which usually has the same beginning-middle-end pattern. We begin with a question (Who is the Wizard of Oz?), pass through attempts to answer it, and conclude with the question answered. (The Wizard is a fraud.) Most feature-length films are composed of several developmental patterns.

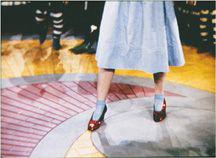

2.18 Dorothy puts her feet on the literal beginning of the Yellow Brick Road, as it widens out from a thin line.

In order to analyze a film’s pattern of development, it is usually a good idea to make a

segmentation.

A segmentation is simply a written outline of the film that breaks it into its major and minor parts, with the parts marked by consecutive numbers or letters. If a narrative film has 40

scenes,

then we can label each scene with a number running from 1 to 40. It may be useful to divide some parts further (for example, scenes 6a and 6b). Segmenting a film enables us not only to notice similarities and differences among parts but also to plot the overall formal progression. Following is a segmentation for

The Wizard of Oz.

(In segmenting films, we’ll label the opening credits with a “C,” the end title with an “E,” and all other segments with numbers.)

C. Credits

- Kansas

- Dorothy is at home, worried about Miss Gulch’s threat to Toto.

- Running away, Dorothy meets Professor Marvel, who induces her to return home.

- A tornado lifts the house, with Dorothy and Toto, into the sky.

- Dorothy is at home, worried about Miss Gulch’s threat to Toto.

- Munchkin City

- Dorothy meets Glinda, and the Munchkins celebrate the death of the Wicked Witch of the East.

- The Wicked Witch of the West threatens Dorothy over the Ruby Slippers.

- Glinda sends Dorothy to seek the Wizard’s help.

- Dorothy meets Glinda, and the Munchkins celebrate the death of the Wicked Witch of the East.

- The Yellow Brick Road

- Dorothy meets the Scarecrow.

- Dorothy meets the Tin Man.

- Dorothy meets the Cowardly Lion.

- Dorothy meets the Scarecrow.

- The Emerald City

- The Witch creates a poppy field near the city, but Glinda rescues the travelers.

- The group is welcomed by the city’s citizens.

- As they wait to see the Wizard, the Lion sings of being king.

- The terrifying Wizard agrees to help the group if they obtain the Wicked Witch’s broomstick.

- The Witch creates a poppy field near the city, but Glinda rescues the travelers.

- The Witch’s castle and nearby woods

- In the woods, flying monkeys carry off Dorothy and Toto.

- The Witch realizes that she must kill Dorothy to get the ruby slippers.

- The Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Lion sneak into the Castle; in the ensuing chase, Dorothy kills the Witch.

- In the woods, flying monkeys carry off Dorothy and Toto.

- The Emerald City

- Although revealed as a humbug, the Wizard grants the wishes of the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Lion.

- Dorothy fails to leave in the Wizard’s hot-air balloon but is transported home by the ruby slippers.

- Although revealed as a humbug, the Wizard grants the wishes of the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Lion.

- Kansas—Dorothy describes Oz to her family and friends

E.

End credits

Preparing a segmentation may look a little fussy, but in the course of this book, we’ll try to convince you that it sheds a lot of light on films. For now, just consider this comparison.

As you walk into a building, your experience develops over time. In many cathedrals, for example, the entryway is fairly narrow. But as you emerge into the open area inside (the nave), space expands outward and upward, your sense of your body seems to shrink, and your attention is directed toward the altar, centrally located in the distance. The somewhat cramped entryway makes you feel a contrast when you enter the broad and soaring space. Your experience has been as carefully planned as any theme park ride. Only by thinking back on it can you realize that the planned progression of the building’s different parts shaped your experience. If you could study the builder’s blueprints, you’d see the whole layout at a glance. It would be very different from your moment-by-moment experience of it, but it would shed light on how your experience was shaped.

A film isn’t that different. As we watch the film, we’re in the thick of it. We follow the formal development moment by moment, and we may get more and more involved. If we want to study the overall shape of things, though, we need to stand back a bit. Films don’t come with blueprints, but by creating a plot segmentation, we can get a comparable sense of the film’s overall design. In a way, we’re recovering the basic architecture of the movie. A segmentation lets us see the patterning that we felt intuitively in watching the film. In

Chapters 3

and

10

, we’ll consider how to segment different types of films, and several of our sample analyses in

Chapter 11

will use segmentations to show how the films work.

Another way to size up how a film develops formally is to

compare the beginning with the ending.

By looking at the similarities and the differences between the beginning and the ending, we can start to understand the overall pattern of the film. We can test this advice on

The Wizard of Oz.

A comparison of the beginning and the ending reveals that Dorothy’s journey ends with her return home; the journey, a search for an ideal place “over the rainbow,” has turned into a search for a way back to Kansas. The final scene repeats and develops the narrative elements of the opening. Stylistically, the beginning and ending are the only parts that use black-and-white film stock. This repetition supports the contrast the narrative creates between the dreamland of Oz and the bleak landscape of Kansas.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

If beginnings are important, then the very beginning is even more important, as “First shots” demonstrates.

At the film’s end, Professor Marvel comes to visit Dorothy

(

2.19

),

reversing the situation of her visit to him when she had tried to run away. At the beginning, he had convinced her to return home; then, as the Wizard in the Oz section, he had also represented her hopes of returning home. Finally, when she recognizes Professor Marvel and the farmhands as the basis of the characters in her dream, she remembers how much she had wanted to come home from Oz.