B0041VYHGW EBOK (30 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Stories surround us. In childhood, we learn fairy tales and myths. As we grow up, we read short stories, novels, history, and biography. Religion, philosophy, and science often present their doctrines through parables and tales. Plays tell stories, as do films, television shows, comic books, paintings, dance, and many other cultural phenomena. Much of our conversation is taken up with telling tales—recalling a past event or telling a joke. Even newspaper articles are called stories, and when we ask for an explanation of something, we may say, “What’s the story?” We can’t escape even by going to sleep, since we often experience our dreams as little narratives. Narrative is a fundamental way that humans make sense of the world.

The prevalence of stories in our lives is one reason that we need to take a close look at how films may embody

narrative form

. When we speak of “going to the movies,” we almost always mean that we are going to see a narrative film—a film that tells a story.

Narrative form is most common in fictional films, but it can appear in all other basic types. For instance, documentaries often employ narrative form.

Primary

tells the story of how Hubert Humphrey and John F. Kennedy campaigned in the Wisconsin presidential primary of 1960. Many animated films, such as Disney features and Warner Bros. short cartoons, also tell stories. Some experimental and avantgarde films use narrative form, although the story or the way it is told may be quite unusual, as we shall see in

Chapter 10

.

Because stories are all around us, spectators approach a narrative film with definite expectations. We may know a great deal about the particular story the film will tell. Perhaps we have read the book on which a film is based, or we have seen the film to which this is a sequel. More generally, though, we have anticipations that are characteristic of narrative form itself. We assume that there will be characters and some action that will involve them with one another. We expect a series of incidents that will be connected in some way. We also probably expect that the problems or conflicts arising in the course of the action will achieve some final state—either they will be resolved or, at least, a new light will be cast on them. A spectator comes prepared to make sense of a narrative film.

As the viewer watches the film, she or he picks up cues, recalls information, anticipates what will follow, and generally participates in the creation of the film’s form. The film shapes particular expectations by summoning up curiosity, suspense, and surprise. The ending has the task of satisfying or cheating the expectations prompted by the film as a whole. The ending may also activate memory by cueing the spectator to review earlier events, possibly considering them in a new light. When

The Sixth Sense

was released in 1999, many moviegoers were so intrigued by the surprise twist at the end that they returned to see the film again and trace how their expectations had been manipulated. Something similar happened with

The Prestige

(see

pp. 302

–303). As we examine narrative form, we consider at various points how it engages the viewer in a dynamic activity.

“Narrative is one of the ways in which knowledge is organized. I have always thought it was the most important way to transmit and receive knowledge. I am less certain of that now—but the craving for narrative has never lessened, and the hunger for it is as keen as it was on Mt. Sinai or Calvary or the middle of the fens.”

— Toni Morrison, author,

Beloved

We can consider a

narrative

to be

a chain of events linked by cause and effect and occurring in time and space.

A narrative is what we usually mean by the term

story,

although we shall be using

story

in a slightly different way later. Typically, a narrative begins with one situation; a series of changes occurs according to a pattern of cause and effect; finally, a new situation arises that brings about the end of the narrative. Our engagement with the story depends on our understanding of the pattern of change and stability, cause and effect, time and space.

All the components of our definition—causality, time, and space—are important to narratives in most media, but causality and time are central. A random string of events is hard to understand as a story. Consider the following actions: “A man tosses and turns, unable to sleep. A mirror breaks. A telephone rings.” We have trouble grasping this as a narrative because we are unable to determine the causal or temporal relations among the events.

Consider a new description of these same events: “A man has a fight with his boss; he tosses and turns that night, unable to sleep. In the morning, he is still so angry that he smashes the mirror while shaving. Then his telephone rings; his boss has called to apologize.”

We now have a narrative. We can connect the events spatially: the man is in the office, then in his bed; the mirror is in the bathroom; the phone is somewhere else in his home. More important, we can understand that the three events are part of a series of causes and effects. The argument with the boss causes the sleeplessness and the broken mirror. The phone call from the boss resolves the conflict; the narrative ends. In this example, time is important, too. The sleepless night occurs before the breaking of the mirror, which in turn occurs before the phone call; all of the action runs from one day to the following morning. The narrative develops from an initial situation of conflict between employee and boss, through a series of events caused by the conflict, to the resolution of the conflict. Simple and minimal as our example is, it shows how important causality, space, and time are to narrative form.

“I had actually trapped myself in a story that was very convoluted, and I would have been able to cut more later if I’d simplified it at the script stage, but I’d reached a point where I was up against a wall of story logic. If I had cut too much at that stage, the audience would have felt lost.”

— James Cameron, director,

Aliens

The fact that a narrative relies on causality, time, and space doesn’t mean that other formal principles can’t govern the film. For instance, a narrative may make use of parallelism. As

Chapter 2

points out (

pp. 68

–70), parallelism presents a similarity among different elements. Our example was the way that

The Wizard of Oz

made the three Kansas farmhands parallel to Dorothy’s three Oz companions. A narrative may cue us to draw parallels among characters, settings, situations, times of day, or any other elements. In Veřá Chytilová’s

Something Different,

scenes from the life of a housewife and from the career of a gymnast are presented in alternation. Since the two women never meet and lead entirely separate lives, there is no way that we can connect the two stories causally. Instead, we compare and contrast the two women’s actions and situations—that is, we draw parallels.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

For a more theoretical discussion of the concept of narrative, using the stories offered up during the 2008 presidential campaign, see “It was a dark and stormy campaign,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=2962

.

The documentary

Hoop Dreams

makes even stronger use of parallels. Two high school students from Chicago’s black ghetto dream of becoming professional basketball players, and the film follows as each one pursues his athletic career. The film’s form invites us to compare and contrast their personalities, the obstacles they face, and the choices they make. In addition, the film creates parallels between their high schools, their coaches, their parents, and older male relatives who vicariously pursue their own dreams of athletic glory. Parallelism allows the film to become richer and more complex than it might have been had it concentrated on only one protagonist.

Yet

Hoop Dreams,

like

Something Different,

is still a narrative film. Each of the two lines of action is organized by time, space, and causality. The film suggests some broad causal forces as well. Both young men have grown up in urban poverty, and because sports is the most visible sign of success for them, they turn their hopes in that direction.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Sequels can extend a story and even jump back in time if a prequel is made. We discuss prequels in “Originality and origin stories.”

We make sense of a narrative, then, by identifying its events and linking them by cause and effect, time, and space. As viewers, we do other things as well. We often infer events that are not explicitly presented, and we recognize the presence of material that is extraneous to the story world. In order to describe how we manage to do these things, we can draw a distinction between

story

and

plot

(sometimes called

discourse

). This isn’t a difficult distinction to grasp, but we still need to examine it in a little more detail.

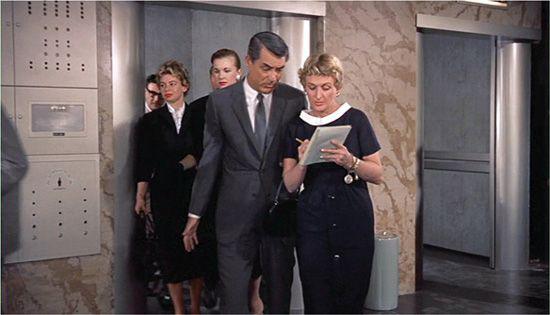

We often make assumptions and inferences about events in a narrative. For instance, at the start of Alfred Hitchcock’s

North by Northwest,

we know we are in Manhattan at rush hour. The cues stand out clearly: skyscrapers, bustling pedestrians, congested traffic

(

3.1

).

Then we watch Roger Thornhill as he leaves an elevator with his secretary, Maggie, and strides through the lobby, dictating memos

(

3.2

).

On the basis of these cues, we start to draw some conclusions. Thornhill is an executive who leads a busy life. We assume that before we saw Thornhill and Maggie, he was also dictating to her; we have come in on the middle of a string of events in time. We also assume that the dictating began in the office, before they got on the elevator. In other words, we infer causes, a temporal sequence, and another locale even though none of this information has been directly presented. We are probably not aware of having made these inferences, but they are no less firm for going unnoticed.

3.1 Hurrying Manhattan pedestrians in

North by Northwest.

3.2 Maggie takes dictation from Roger Thornhill.

The set of

all

the events in a narrative, both the ones explicitly presented and those the viewer infers, constitutes the

story

. In our example, the story would consist of at least two depicted events and two inferred ones. We can list them, putting the inferred events in parentheses: