B0041VYHGW EBOK (37 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

On the other hand, objectivity can be an effective way of withholding information. One reason that

The Big Sleep

does not treat Marlowe subjectively is that the detective genre demands that the detective’s reasoning be concealed from the viewer. The mystery is more mysterious if we do not know the investigator’s hunches and conclusions before he reveals them at the end.

A film need not be in the mystery genre in order to exploit objective and restricted narration. Julia Loktev’s

Day Night Day Night

follows a young woman who has been recruited as a suicide bomber. We see her accepted into the group, awaiting orders, and eventually embarking on the mission. One scene utilizes optical point of view extensively, while another does so briefly. There are a few moments of auditory subjectivity, when the noises of street traffic drop out. Yet these flashes of subjective depth stand out against an overwhelmingly objective presentation. For nearly the entire film, we have to assess the woman’s state of mind purely through her physical behavior. Moreover, our information about the story action is very limited. We are never told what political group has recruited her or why she has volunteered for the task. The woman herself does not know the plan, the members of the terrorist group, or the reasons she was picked. In fact, we know less than she does, because we get only hints about her past life. The impersonal, tightly restricted narration of

Day Night Day Night

not only creates suspense about her mission but also encourages curiosity about a rather large number of story events.

At any moment in a film, we can ask, “How deeply do I know the characters’ perceptions, feelings, and thoughts?” The answer will point directly to how the narration is presenting or withholding story information in order to achieve a specific effect on the viewer.

In all of these examples, the filmmaker’s choice about range or depth affects how the spectator responds to the film as it progresses.

Narration, then, is the process by which the plot presents story information to the spectator. This process may shift between restricted and unrestricted ranges of knowledge and varying degrees of objectivity and subjectivity. Narration may also use a

narrator,

some specific agent who purports to be telling us the story.

A CLOSER LOOK

WHEN THE LIGHTS GO DOWN, THE NARRATION STARTS

When we open a novel for the first time, we don’t expect the story action to start on the copyright page. Nor do we expect to find the story’s last scene on the back cover. But films can start emitting narrative information in the credit sequences and continue to the very last moments we’re in the theater.

Credit sequences serve to identify the participants in a production, and today the list can run many minutes. In the late 1910s, filmmakers realized that credits could be enlivened by drawings and paintings keyed to the film

(

3.27

).

Since the 1920s, the credits’ graphic design and musical accompaniment have often quickly conjured up the time and place of the story

(

3.28

).

The breezy credits of Truffaut’s

Jules and Jim

offer glimpses of the action to come while firmly establishing the two young men’s friendship in turn-of-the-century Paris.

3.27 An early example of illustrated credits for the 1917 comedy

Reaching for the Moon.

3.28

Raw Deal,

a crime film from 1948, begins in prison, and the credit sequence suggests the locale before the action begins.

An overall mood is often set simply by music playing over simple titles, as in

The Exorcist,

but the credits can take a more active role through type fonts, color, or movement. Saul Bass, a celebrated designer of corporate logos, gave Alfred Hitchcock’s and Otto Preminger’s films dynamic geometric designs

(

3.29

).

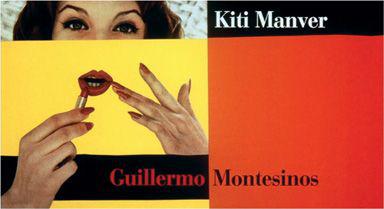

Rainer Werner Fassbinder was famous for his imaginative credit sequences, some in homage to the 1950s Hollywood melodramas he admired. In a similar vein, the brash collages in Pedro Almodóvar’s credit sequences lead us to expect sexy irreverence

(

3.30

).

3.29 Saul Bass’s elegantly simple credits for

Advise and Consent

hint that the story will lift the lid off Washington scandals.

3.30 A collage design suggesting sophistication and glamorous lifestyles (

Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown

).

Plot elements can be announced quite specifically. Illustrations can anticipate particular scenes

(

3.31

).

Se7en

’s scratchy glimpses of cutting, stitching, and defacement launched a cycle of nightmarish credit sequences showing violation and dismemberment.

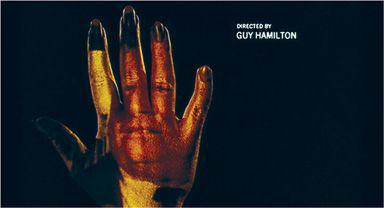

Goldfinger

’s credits present a key motif and anticipate several scenes

(

3.32

).

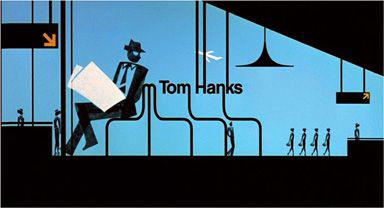

Many of the scenes in

Catch Me If You Can

are previewed in the title sequence, which pays affectionate homage to the animated credit sequences of the film’s period

(

3.33

).

More subtly, the opening of

The Thomas Crown Affair

(1999) hints at the method by which the hero will steal a painting.

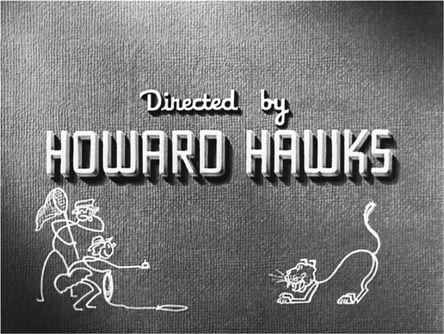

3.31 Some of the stick-figure credits in

Bringing Up Baby

anticipate scenes that will take place in the story action.

3.32

Goldfinger:

The gilded woman herself will reappear in the film, while other scenes to come are projected on areas of her body.

3.33 The streamlined animation of

Catch Me If You Can

evokes 1960s credit sequences while previewing story action and settings. Here the Tom Hanks character starts to trail Leonardo DiCaprio, who plays an impostor pretending to be an airline pilot.

Films often end their plot with an epilogue that celebrates the stable state that the characters have achieved, and that situation can be presented in tandem with the credits

(

3.34

).

Sometimes key scenes will be replayed under the final credits, or new plot action will be shown.

Airplane!

began a fashion for weaving running gags into its final credits.

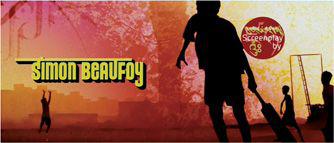

3.34 In

Slumdog Millionaire,

the dance epilogue in the railway station is intercut with the major credits, which recall scenes from the film.

Occasionally, the filmmaker fools us. We think the plot has ended, and a long list of personnel crawls upward. But then the film tacks an image on the very end

(

3.35

).

These “credit cookies” remind us that an enterprising filmmaker may exploit every moment of the film’s running time to engage our narrative expectations.

3.35 Takeshi Kitano’s

Sonatine

follows its final credit sequence with desolate images of a beach, wistfully reminding us of earlier scenes showing childish gangsters at play.