B0041VYHGW EBOK (34 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

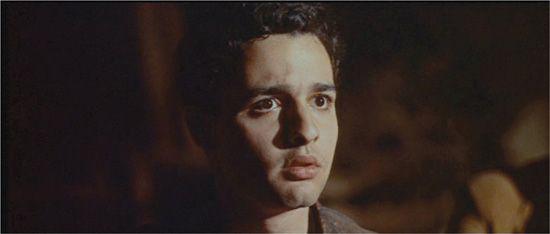

Normally, the place of the story action is also that of the plot, but sometimes the plot leads us to infer other locales as part of the story. We never see Roger Thornhill’s office or the colleges that kicked Kane out. Thus the narrative may ask us to imagine spaces and actions that are never shown. In Otto Preminger’s

Exodus,

one scene is devoted to Dov Landau’s interrogation by a terrorist organization he wants to join. Dov reluctantly tells his questioners of life in a Nazi concentration camp

(

3.13

).

Although the film never shows this locale through a flashback, much of the scene’s emotional power depends on our using our imagination to fill in Dov’s sketchy description of the camp.

3.13 In

Exodus,

Dov Landau recounts his traumatic stay in a concentration camp. Instead of presenting this through a flashback, the narration dwells on his face, leaving us to visualize his ordeal.

“The multiple points of view replaced the linear story. Watching a repeated action or an intersection happen again and again … they hold the audience in the story. It’s like watching a puzzle unfold.”

— Gus van Sant, director, on

Elephant

Further, we can introduce an idea akin to the concept of screen duration. Besides story space and plot space, cinema employs screen space: the visible space within the frame. We’ll consider screen space and offscreen space in detail in

Chapter 5

, when we analyze framing as a cinematographic technique. For now, it’s enough to say that, just as screen duration selects certain plot spans for presentation, so screen space selects portions of plot space.

In

Chapter 2

, our discussion of formal development in general within the film suggested that it’s often useful to compare beginnings and endings. A narrative’s use of causality, time, and space usually involves a change from an initial situation to a final situation.

A film does not just start, it

begins.

The opening provides a basis for what is to come and initiates us into the narrative. In some cases, the plot will seek to arouse curiosity by bringing us into a series of actions that has already started. (This is called opening

in medias res,

a Latin phrase meaning “in the middle of things.”) The viewer speculates on possible causes of the events presented.

The Usual Suspects

begins with a mysterious man named Keyser Söze killing one of the main characters and setting fire to a ship. Much of the rest of the film deals with how these events came to pass. In other cases, the film begins by telling us about the characters and their situations before any major actions occur.

Either way, some of the actions that took place before the plot started will be stated or suggested so that we can start to connect up the whole story. The portion of the plot that lays out important story events and character traits in the opening situation is called the

exposition.

In general, the opening raises our expectations by setting up a specific range of possible causes for and effects of what we see. Indeed, the first quarter or so of a film’s plot is often referred to as the

setup.

As the plot proceeds, the causes and effects will define narrower patterns of development. There is no exhaustive list of possible plot patterns, but several kinds crop up frequently enough to be worth mentioning.

Most patterns of plot development depend heavily on the ways that causes and effects create a change in a character’s situation. The most common general pattern is a

change in knowledge.

Very often, a character learns something in the course of the action, with the most crucial knowledge coming at the final turning point of the plot. In

Witness,

when John Book, hiding out on an Amish farm, learns that his partner has been killed, his rage soon leads to a climactic shoot-out.

A very common pattern of development is the

goal-oriented

plot, in which a character takes steps to achieve a desired object or state of affairs. Plots based on

searches

would be instances of the goal plot. In

Raiders of the Lost Ark,

the protagonists try to find the Ark of the Covenant; in

Le Million,

characters search for a missing lottery ticket; in

North by Northwest,

Roger Thornhill looks for George Kaplan. A variation on the goal-oriented plot pattern is the

investigation,

so typical of detective films, in which the protagonist’s goal is not an object, but information, usually about mysterious causes. In more strongly psychological films, such as Fellini’s

8½,

the search and the investigation become internalized when the protagonist, a noted film director, attempts to discover the source of his creative problems.

Time or space may also provide plot patterns. A framing situation in the present may initiate a series of flashbacks showing how events led up to the present situation, as in

The Usual Suspects’

flashbacks.

Hoop Dreams

is organized around the two main characters’ high school careers, with each part of the film devoted to a year of their lives. The plot may also create a specific duration for the action—a

deadline.

In

Back to the Future,

the hero must synchronize his time machine with a bolt of lightning at a specific moment in order to return to the present. This creates a goal toward which he must struggle. Or the plot may create patterns of repeated action via cycles of events: the familiar “here we go again” pattern. Such a pattern occurs in Woody Allen’s

Zelig,

in which the chameleon-like hero repeatedly loses his own identity by imitating the people around him.

Space can also become the basis for a plot pattern. This usually happens when the action is confined to a single locale, such as a train (Anthony Mann’s

The Tall Target

) or a home (Sidney Lumet’s

Long Day’s Journey into Night

).

A given plot can, of course, combine these patterns. Many films built around a journey, such as

The Wizard of Oz

or

North by Northwest,

involve deadlines.

The Usual Suspects

puts its flashbacks at the service of an investigation. Jacques Tati’s

Mr. Hulot’s Holiday

uses both spatial and temporal patterns to structure its comic plot. The plot confines itself to a beachside resort and its neighboring areas, and it consumes one week of a summer vacation. Each day certain routines recur: morning exercise, lunch, afternoon outings, dinner, evening entertainment. Much of the film’s humor relies on the way that Mr. Hulot alienates the other guests and the townspeople by disrupting their conventional habits

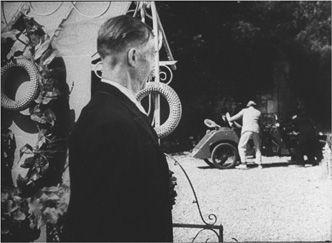

(

3.14

).

Although cause and effect still operate in

Mr. Hulot’s Holiday,

time and space are central to the plot’s formal patterning.

3.14 In

Mr. Hulot’s Holiday,

Hulot’s aged, noisy car has a flat tire that breaks up a funeral.

For any pattern of development, the spectator will create specific expectations. As the film trains the viewer in its particular form, these expectations become more and more precise. Once we comprehend Dorothy’s desire to go home, we see her every action as furthering or delaying her progress toward her goal. Thus her trip through Oz is hardly a sightseeing tour. Each step of her journey (to the Emerald City, to the Witch’s castle, to the Emerald City again) is governed by the same principle—her desire to go home.

In any film, the pattern of development in the middle portion may delay an expected outcome. When Dorothy at last reaches the Wizard, he sets up a new obstacle for her by demanding the Witch’s broom. Similarly, in

North by Northwest,

Hitchcock’s journey plot constantly postpones Roger Thornhill’s discovery of the Kaplan hoax, and this, too, creates suspense. The pattern of development may also create surprise, the cheating of an expectation, as when Dorothy discovers that the Wizard is a fraud or when Thornhill sees the minion Leonard fire point-blank at his boss Van Damm. Patterns of development encourage the spectator to form longterm expectations that can be delayed, cheated, or gratified.

A film doesn’t simply stop; it

ends.

The narrative will typically resolve its causal issues by bringing the development to a high point, or

climax.

In the climax, the action is presented as having a narrow range of possible outcomes. At the climax of

North by Northwest,

Roger and Eve are dangling off Mount Rushmore, and there are only two possibilities: they will fall, or they will be saved.

Because the climax focuses possible outcomes so narrowly, it typically serves to settle the causal issues that have run through the film. In the documentary

Primary,

the climax takes place on election night; both Kennedy and Humphrey await the voters’ verdict and finally learn the winner. In

Jaws,

several battles with the shark climax in the destruction of the boat, the death of Captain Quint, the apparent death of Hooper, and Brody’s final victory. In such films, the ending resolves, or closes off, the chains of cause and effect.

Emotionally, the climax aims to lift the viewer to a high degree of tension or suspense. Since the viewer knows that there are relatively few ways the action can develop, she or he can hope for a fairly specific outcome. In the climax of many films, formal resolution coincides with an emotional satisfaction.

A few narratives, however, are deliberately anticlimactic. Having created expectations about how the cause–effect chain will be resolved, the film scotches them by refusing to settle things definitely. One famous example is the last shot of

The 400 Blows

(

p. 84

). In Michelangelo Antonioni’s

L’Eclisse

(“The Eclipse”), the two lovers vow to meet for a final reconciliation but aren’t shown doing so.

In such films, the ending remains relatively open. That is, the plot leaves us uncertain about the final consequences of the story events. Our response becomes less firm than it does when a film has a clear-cut climax and resolution. The form may encourage us to imagine what might happen next or to reflect on other ways in which our expectations might have been fulfilled.

A plot presents or implies story information. The opening of

North by Northwest

shows Manhattan at rush hour and introduces Roger Thornhill as an advertising executive; it also suggests that he has been busily dictating before we see him. Filmmakers have long realized that the spectator’s interest can be aroused and manipulated by carefully divulging story information at various points. In general, when we go to a film, we know relatively little about the story; by the end, we know a lot more, usually the whole story. What happens in between?

The plot may arrange cues in ways that withhold information for the sake of curiosity or surprise. Or the plot may supply information in such a way as to create expectations or increase suspense. All these processes constitute

narration

, the plot’s way of distributing story information in order to achieve specific effects. Narration is the moment-by-moment process that guides us in building the story out of the plot. Many factors enter into narration, but the most important ones for our purposes involve the

range

and the

depth

of story information that the plot presents.

The plot of D. W. Griffith’s

The Birth of a Nation

begins by recounting how slaves were brought to America and how people debated the need to free them. The plot then shows two families, the northern Stoneman family and the southern Camerons. The plot also dwells on political matters, including Lincoln’s hope of averting civil war. From the start, then, our range of knowledge is very broad. The plot takes us across historical periods, regions of the country, and various groups of characters. This breadth of story information continues throughout the film. When Ben Cameron founds the Ku Klux Klan, we know about it at the moment the idea strikes him, long before the other characters learn of it. At the climax, we know that the Klan is riding to rescue several characters besieged in a cabin, but the besieged people do not know this. On the whole, in

The Birth of a Nation,

the narration is very

unrestricted:

We know more, we see and hear more, than any of the characters can. Such extremely knowledgeable narration is often called

omniscient narration.