Back of Beyond (27 page)

But things had changed since my last visit. Kit had died a few months previously and someone else was running the bookstore.

There were other, happier changes in Hawes. “It’s that vet chap, James Herriot, with all his books on the Dales,” said John Jeffryes at Simonstone Hall hotel. “He’s put the whole area on the map.” Brian and Cherry Guest at Cockett’s Hotel in the town center, and the Jutsums at their newly refurbished Rookhurst Country House, all agree that a new surge of tourism has raised standards. “It’s not just a whistle-stop any longer,” said Susan Jutsum. “People come to stay now and walk. It’s very different from before. Very exciting too. We can serve dishes we’d never dare to ten years ago.”

A constant source of curiosity to explorers of these hills are the often bizzare traditions still proudly maintained by towns and villages in and around the Northern Pennines. Appleby in the Vale of Eden hosts a week-long Horse Fair in June, which attracts hundreds of gypsies, complete with Romany caravans and palm readers, and the tiny community of West Witton down Wensleydale dramatizes the

Burning of Bartle

in late August. Allendale Town celebrates New Year with a Norse pagan “fire festival” serene and secluded Semerwater holds a “blessing of the water” ceremony in August, and at Ripon, a market town on the eastern fringe of the Dales, a centuries-old custom of horn-blowing every night in the main square is still preserved. A similar ritual takes place every evening at the nearby village of Bain-bridge.

I hitched a lift to this model twelfth-century village built for foresters around a broad green. Every night at 9:00

P.M.

prompt, from September 28 to February’s Shrovetide, a villager (invariably a member of the Metcalfe family) has given three long blasts on a horn for the past seven hundred years. Originally it was intended as a guide for travelers in the forest but the forest has long since gone and the tradition is kept alive by ten-year-old Alistair Metcalfe, who dutifully steps out onto the green and blows the three-foot-long South African Cape Buffalo horn “just before I go to bed.” His uncle, Jack Metcalfe, who died in 1983 after thirty-six years of horn blowing, was once asked if it was true that a good blast carried over three miles. His reply was typical Yorkshire: “How should I know? I’m at this end.”

A few miles farther across more wind-torn wastes, the Pennine Way does its vanishing act again, and then comes Tan Hill Inn, the highest pub in England. Scattered around in the heather were the tops of stone-lined shafts, relics of “brown-coal” mining, which has flourished here since the thirteenth century, when the soft peaty coal was transported by packhorse to the great abbeys down-dale.

A chart inside the cozy pub indicated more than one hundred miles of tunnels on the plateau, and a blazing fire suggested the landlord is never short of supplies. “He can nip out and just pick it up,” said the barman, stroking the comb of Eric the cock and the neck of Nasher the dog simultaneously. It’s a zany kind of place, ideal for bedraggled hikers looking for light relief. A group in the corner huddled over dominoes, a bearded giant snored on the sofa with a tiny waiflike girlfriend in his arms, and a woman with wild eyes told witching tales to no one in particular by the fire. A well-dressed couple arrived, took one look at the odd mélange, and vanished.

After Tan Hill, I descended through a silver world of moist mists, and in the buzzing silence I sensed the timelessness of these ancient hills—flickers of infinity rarely found in the frantic little worlds far below.

At the reservoir in Baldersdale I celebrated the Pennine Way halfway point with handfuls of ice-cold spring water and then—just as my ankle gave way for the third time that week after another tumble on tussocks—came Hannah.

“Tha’s gone and hurt thisself, then?”

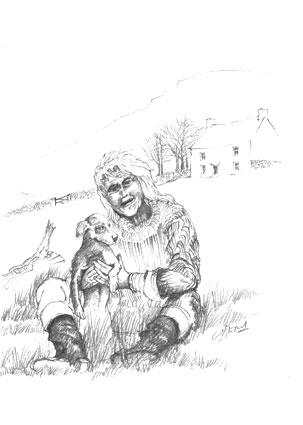

A middle-aged woman in a tattered purple pullover and baggy black trousers held up by a loop of string stood with a shovel in a pile of manure. Her cheeks were holly-berry bright, her hair, brilliantly silver, haloed her head.

“Come n’ sit thisself down a bit, please” she said, indicating a tiny milking stool in the cow byre. “Just give me a minute. Bessie’s got excited and made messies. I’m a bit particular and I hate walkin’ in clarts. If there’s one clart about you carry it around all day.”

She cleaned up meticulously and let me into her dark farmhouse where she’d lived alone since her mother’s death in 1958. The kitchen was crammed with cardboard boxes piled halfway to the ceiling, and it was only later that I found out what they all contained. We huddled around a tiny electric heater and she served me glasses of fresh milk while her Jack Russell terrier, Tim, pranced around trying to get a sip.

She told me about her love for her little valley. “I don’t go far but I don’t need to. There’s nothin’ I like better than goin’ through that iron gate and down among the trees and the water. That little stream by the first bridge. I go there a lot.”

We talked about her five cows. “I can’t afford more but I enjoy what I have. They’re just like people—some have a calm temperament, others are excitable, and a few can be downright bossy and nasty.”

I wondered if she ever got lonely. “Oh never, never. I’ve so many things I want to do. There’s the wallin’, slatin’, there’s weedin’, muckin’ out. I’m going to make jam. I used to make butter too. I can still hear that sound when it, what we call, ‘broke’—a lovely slushin’ sound as it got thicker. Oh no, I’ll never catch up with myself. Some people free themselves up and they’ve got lots of time and no idea what to do with it.”

She noticed I was still limping. “I’m a great one for walkin’ sticks,” she said and vanished. Five minutes later she was back with a fresh-cut ash stick. “It’s a clumsy brute,” she apologized. “I’ll just dress it up a bit to neaten it, please.” I held it while she stripped the bark from the handle and tip with a pocketknife.

She seemed one of those people gifted with a natural earthy wisdom. “Success seems to me to be much more than just a lot of things lying around—there’s as many ways of success as there are people.”

Very reluctantly I left Hannah and limped up the long hill from the farm with my new stick. She stood waving all the time. “Come back, please, if it hurts” was the last I heard.

Later that night the barmaid at the Rose and Crown Pub in Mickleton told me I’d just spent the afternoon with Hannah Hauxwell, whose happy face has become the stuff of legends following a TV documentary on her life. And the cardboard boxes? “Oh, they’re full of letters,” she said, “from people all over the world. She’s living in a house bursting with love.”

Middleton-in-Teesdale, a nineteenth-century lead-mining center, has a demure charm, and I should have remained there safely sketching under the shade trees on the green. Instead I hurried around buying sugary supplies (for instant energy I told myself) and was quickly alongside the cascading river Tees on what I hoped would be one of the big walks of the journey.

The day sparkled and the light seemed to have its source not in the sun but in the valley itself which glowed a fluorescent green below the darker fells. Near High Force, where the narrowed river tumbles dramatically over an outcrop of hard dolerite, there were people peering intently at the ground looking for the last summer showings of rare plants. At Widdybank Fell, a rare band of “sugar” limestone creates special alkaline soil conditions ideal for the elusive spring gentian, the pink bird’s-eye primrose, the bog sandwort, the purple mountain pansy, and a host of other species. Botanists flock here, and the construction of the vast Cow Green Reservoir above the Cauldron Snout falls in 1971 brought howls of protest from around the world. The bleak geometry of the dam wall seemed out of place in the wild scenery, and I was glad to be climbing into the hills again.

High Cup comes as a surprise, an abrupt dropping of the land down dolerite cliffs and a graceful easing of Pennine hills into the Vale of Eden, edged on the far horizon by the dramatic fells of the Lake District. This is one of the most impressive vistas along the Pennine Way, and I sat for an hour in a patch of wild thyme, watching the weather. I counted five simultaneous patterns from valley floor mists to thunderstorms in the Scottish border country where lightning played over the hills like snakes with broken spines. I waited in vain for the Helm wind, a unique local phenomenon caused by the abrupt meeting of mountains and plain.

“Waitin’ for t’ Helm?” A tall, rake-thin figure with a gray beard hanging down his chest appeared suddenly from behind a tumble of boulders near the precipice. His torn coat and trousers were the same muddy brown color as the rocks, and he walked slowly with a limp, supporting himself on a stick as angular as the lightning in the distance.

“T’ Helm—it’s a wild wind that blows here where t’ mountains drop off to t’ vale. There’s a cloud too—hangs over t’ fell for days.”

“Oh,” was all I managed. I was still wondering where he’d come from.

“Aye well, you won’t get none today. It’s all wrong for it.”

And then he was off, limping around the edge of High Cup like some wild prophet in the wilderness.

Later I made the long descent past Narrowgate Beacon and Peeping Hill down to the pink-stone village of Dufton nestled around a sycamore-shaded green.

“Did you see Moses?” two young hikers asked as I dropped my rucksack by an enormous pink fountain. “He gave us a hell of a scare!”

We asked one of the locals about the odd character in the hills.

“Well we get strange ones now n’then on t’tops. Likely some old shepherd.”

The three of us sprawled on the green, rubbing weary feet and waiting for the youth hostel to open. A raven joined us, legs wide apart like a gunslinger and staring with eyes like black holes until we offered it the remains of a beef sandwich. It gave a look of disgust, shook its head violently, and flapped off across the treetops.

“Moses in disguise!” said one of the hikers.

Why the dog bit me I shall never know.

It was a docile-looking creature, hardly more than rabbit-sized—lolling in a muddy hollow by a barn wall (obviously his favorite resting place, a comfortable earthy couch shaped by years of lolling). I smiled and mumbled some gentle endearment as I strolled by, but it just lay there, watching me, indifferent to my greeting. But it was all an act. Suddenly the fickle creature leaped up, gave a sudden sharp snarl, and sank its teeth into my calf. I whirled round, backpack flying off my shoulder, but it was already in retreat, scarpering around the corner of the barn. I gave half-hearted chase but it knew its game well and vanished.

My leg stung so I sat down, opened up the first-aid kit, and quickly poured some purple iodine over the teeth marks. They were not deep (it takes quite a lot to penetrate two layers of thick walking socks) but I’ve always had a dread of rabies ever since I witnessed the agonies of the traditional injection cure given a friend of mine many years back. He couldn’t sit down—or do much of anything else—for almost two months! I poured more iodine on the wound and it ran down into my boots. The dog was nowhere to be seen but somehow I felt it was still watching me. As I hobbled away I turned for a last look, and there it was, brazen as brass, back at its muddy hole, preparing for the next victim.

The next day was anything but balmy. The morning hike back up onto the open moors was in a petulant drizzle, which became a pitchforked rain as I climbed higher. On the summit of Cross Fell, at 2,930 feet, the highest point of the Pennines, the clouds suddenly descended in clammy tentacles, and I was swallowed up in the first snow of the season—a howling white fury. I could see only a few feet ahead. The path became confused with sheep tracks, and my compass failed to reassure me. I felt very lost and cold on this “Fiends Fell,” its ancient name until St. Augustine brought his Christian influences here in the sixth century and chased out the bogeys by sticking a cross on the summit. I groped around through remnants of old lead mines. There was supposedly a hiker’s hut somewhere for emergencies like this, but I never found it and, looking like a snow monster, I burrowed behind a wall until the storm eased. Much later I sloshed and skidded down the mountainside to the pretty village of Garrigill.