Bayley, Barrington J - Novel 10

Read Bayley, Barrington J - Novel 10 Online

Authors: The Zen Gun (v1.1)

The Zen Gun

Barrington

J. Bayley

Pout,

the chimera, half-man, half-ape, was incorporated into one of the plants or

vice versa. He was jammed in a squatting position, while the stems, entering at

his buttocks, merged with his legs, his arms and his torso, emerging at knees,

elbows,-and through his abdomen and thorax. A large, yellow-petalled flower

seemed to frame his face.

It

was his face that rivetted Ikematsu's attention, while the chimera squirmed in

dumb distress, glaring with huge piteous eyes. For in that face, set into it as

if set in pudding, was the

zen

gun. The gun was his

face, or a part of it. The barrel pointed straight out in place of a nose . . .

the stock merged with and disappeared into Pout's pendulous mouth.

Ikematsu

leaned toward the chimera. "How you loved your toy! Now it is truly

yours!"

Barrington

J. Bayley

in

DAW

editions:

THE PILLARS OF

ETERNITY

THE FALL OF

CHRONOPOLIS

THE GRAND WHEEL

STAR WINDS

THE GARMENTS OF

CAEAN

COLLISION COURSE

Barrington

J, Bayley

DAW

BOOKS, INC.

DONALD

A

.

WOLLHEIM,

PUBLISHER

1633 Broadway,

New

York

,

NY

10019

Copyright ©, 1983, by

Barrington

J. Bayley.

All

Rights Reserved.

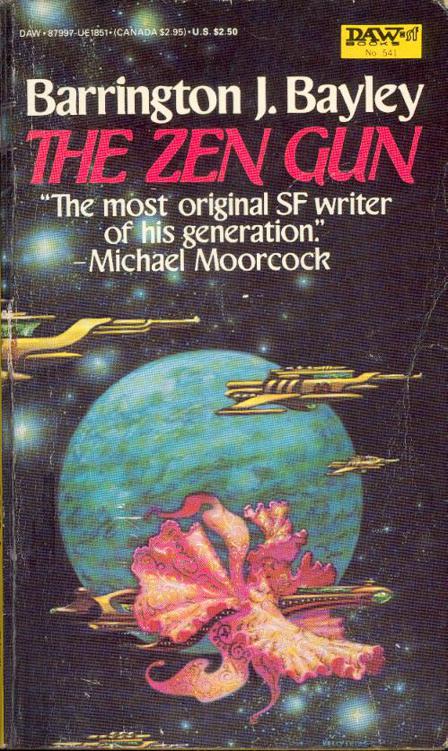

Cover art by Frank Kelly Freas.

FIRST PRINTING.

AUGUST 1983

123456789

DAW

U.S.

PAT. OFF. MARCA

REGISTRADA.

HECHO EN

U.S.A.

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

Around

the blue, green and white planet, Ten-Fleet disposed itself with a suddenness

that was intentionally frightening. On the diagrammatisation screens in the

control centres of both sides, the criss-cross orbits of the hundred and forty

ships resembled the electrons of a heavy atom orbiting an engorged nucleus like

an enclosing web. In the first seconds of the occupation the planet's own

service satellites, a gnat's haze, had been vapourised, the staffs of a dozen

manned stations taken prisoner. Robbed of communications, the planet was

helpless and nearly blind.

Meantime

Ten-Fleet substituted its own satellite haze. Everything on and below the

surface was being monitored at a resolution level of one to one.

Relaxing

in his den, Admiral Archier could imagine the consternation now reigning on the

planet. Its government would be ignorant—or so he hoped—of what he as a

military man understood all too well, namely that to be in a position to blast

a planet by missile, beam or blanket was merely an exercise in military

impotence. The criterion of practical power was the capability to land

effectives, and just as important, to take them off again.

Ten-Fleet

was depleted. If it came to it, Archier would not properly be able to

administrate the cowering population. Its dreadful weaponry was, in that sense,

a threat that could be bluffed.

It

was advisable, therefore, to conduct his business quickly, before the

government down below-began to draw conclusions from the fleet's inaction. The

Admiral did not relish having to make a decision as to whether to punish the

planet for recalcitrance.

Archier

reclined on a mossy bank in the shade of an apple tree. Animals played and gambolled

a short distance away: a dwarf elephant two feet tall; a dwarf giraffe whose

head could crane almost to Archier's shoulder; a chimp, and a bush baby almost

as large.

Disengaging

itself, the elephant strolled over. "The ruling council is in debate right

now," it announced in a slightly trumpety voice. "According to

bounce-back satellite reports, they are talking over ways to cheat us."

Archier

smiled. "No doubt they think they can pass off decorticated murderers as

artistic geniuses. Well, we've seen all that before."

The

giraffe ambled over to rub its neck against his sleeve. "I hope they give

us a good composer," he said in his soft, mild voice. "Would we be

allowed to commission him before we make delivery to Diadem?"

"While we are in semi-autonomous status, yes."

"Admiral,

they are asking to talk to us," the elephant chimed in.

Archier

nodded. He patted the large grey head of his elephant adjutant, whose brain

implant kept it in touch with all of Ten-Fleet's communications. "Come

with me then, Arctus. I might need you to keep me informed."

From

his present vantage point the mossy wood had no visible limits. But when

Archier stepped behind the apple tree to stroll through the dappled light of

the grove, Arctus padding along behind him, he was suddenly in a wide,

carpeted corridor bearing a steady traffic of men, women, children and animals.

A short walk brought him to the official audience chamber. A spider monkey

looked up and lifted a hand in salute. Then it began to set up the meeting.

Admiral

Archier took his cloak of rank from a nearby peg and self-consciously seated

himself upon the throne before the view area. Subdued lights came on. He felt

the mantle of imperial numinousness descend upon him. To those whose images now

sprang to life in the view area his clean, pale features would seem majestic

and almost angelically authoritative, and the glint in his eye would betoken a

chilling perceptiveness.

He

was looking into a council chamber. About twenty people sat around an oval table;

there were no animals present. At the head of the table, raised a little above

the others, was the Chairman of the Rostian Council, an elderly man who bore

his years well, and who wore a white gown that made him look almost clinical. A

short and neatly trimmed white beard sprouted from his chin.

The Chairman was the only one able

to look directly at Archier without having to turn his head. The expression on

his face was that of one who knew the weakness of his position and was forcing

himself to bite back heartfelt defiance.

"Do

I address the representative of the Imperial Directors?" he asked in a

dry, acid tone.

"You

do, but more specifically the Imperial Collector of Taxes," Archier

answered lightly. "As already stated, you are twenty standard years in

default. The matter is serious; your account must be settled forthwith."

"We

are not wilfully in default," the Chairman said with steely grimness.

"Ten years ago we offered to render all due services in credit,

manufactured goods or rare materials. We received no reply."

"I

am your reply. Your offer should not have been made. It bodes the Empire no

service and is interpreted as attempted evasion of payment." Archier

reached out his hand; the spider monkey placed a file of papers on it.

"However, to clear the matter up, the Imperial Inspector of Revenues has

agreed to reduce arrears by fifty percent—on condition that all future levies

are paid promptly at the stipulated ten-standard-year intervals, delivery being

your responsibility."

The

Admiral bent his head to the papers before him. "These are the levies

which will now be paid by you before we depart."

He

began to read from a list.

"One thousand two hundred and

fifty-eight artists of the musical variety, comprising both composers and

performers.

"One thousand two hundred and fifty-eight artists of the

visual, tactile and odoriferous varieties.

"One thousand two hundred and fifty-eight practitioners of the

literary and dramatic arts.

"Two thousand and twenty scientists of assorted disciplines.

"You

are reminded that all persons must -be human, not animal or construct,

containing not more than two percent of dominant animal genes. All persons must

reach at least Grade Twenty on the Carrimer Creativity Test that will be

applied by Fleet psychologists. Further, at least one hundred persons should be

of genius

standard,

or Grade Twenty-Five on the

Carrimer Test."

Archier

looked up and handed back the file to the spider monkey. The faces staring at

him could only be described as stony.

Oh,

I know what you're thinking. We would rather secede from the Empire, that's

what you're thinking. But you dare not speak of rebellion, not openly, not even

here on the fringe, while Ten-Fleet sweeps over your heads."

"This

traffic in people goes quite against the social philosophy we have evolved

here on Rostia!" the Chairman protested. "It is slavery!"

"

Do

not despair, the cream of your nation will be exporting

that philosophy into the Empire generally," Archier retorted amiably.

"Your reluctance is a sad state of affairs. There was a time when the

gifted among us competed for a chance to migrate to the heart of the

Empire."

"Were

that so, this tribute would hardly be necessary."

Archier

leaned forward. "You have told me what you do not like. There is something

/ do not like. I do not like the word 'tribute.' I am here as a tax-gatherer.

We all live under the law. Make arrangements for payment."

The

Chairman bit his lip. "We shall need time if we are to do this. You come

upon us suddenly."

"We

shall not brook any delay. We shall know if you stall for time or plot any

trickery against us. Therefore, I call on you to reassert your allegiance to

the Empire." At this moment Archier became aware that Arctus the elephant

was tugging at his sleeve with its trunk. He leaned aside. "What is it,

Arctus?" he muttered.

The

tiny elephant opened its maw and whispered hoarsely in Archier's ear.

"A message from High Command!"

Straightening,

Archier turned back to the Rostian Council. "Will you kindly begin your

despatches within one

rotation.

Goodbye for now."

With

that end to the conversation, hurried as it was, he rose, thanked the spider

monkey, and left the audience room with Arctus. They passed through curtains of

draped light: mauve, lavender, lilac, finally effervescent lemon.

Suddenly

they were in the space-torsion room.

A

nine-year-old boy was on duty, a son of one of the crew who had been given the

job much as he might have been given a toy. With an eager sense of ceremony he

presented Archier with the message, which had come in word form.

It

was a directive, engraved in glowing letters on a sheet of yellow parchment.

Archier murmured his thanks and scanned it.

After the addressing and

classification codes

came

a terse instruction.

ESCORIA SECTOR IN CONDITION REBELLION.

PROCEED IN FULL

MAJESTY, OBJECT SUPPRESSION,

CONDITION

AUTONOMY.

ENABLING DATA WILL FOLLOW.

Admiral

Archier gazed at the parchment for some time, allowing the key phrases to sink

in.

Full Majesty.

That meant he was to recognise no

constraint on the deployment of the fleet's resources.

Condition Autonomy.

That meant that the fleet had the legal

standing of a sovereign state. In theory it implied that the High Command had

lost its power to act or had even collapsed. He, Archier, could behave as

though

he

were the government of the

Empire, responsible to no one.

If

the rebellion in Escoria could not be dealt with, he could choose to obliterate

all human life there—and was probably expected to do so. Instead of punishing

the planet below by destroying a city or two, he could, likewise, annihilate

it.

The

disintegration of the Empire as an organised and effective entity was plainly

proceeding apace.

He

passed the parchment to Arctus. The elephant took the bottom edge in the tip of

its trunk and raised the sheet before its face.

"Ah.

This is promotion of sorts, sir."

"Is

it?" Archier sounded doleful. "It bodes a less happy set of

circumstances to me."

Ruefully

he thought of the tax reprieve which now had inadvertently befallen Rostia. The

dignity of the Empire would best be served, he thought

,

if Ten-Fleet were to leave without warning, as abruptly as it had come.

"Come,

Arctus,' he sighed, "let's to the Command Room."

Minutes

passed. And then the web of orbits surrounding Rostia faded from the

diagrammatisation screens, though the thousand or so satellites were expendable

and remained, a replacement gift for the planet that, Admiral Archier feared,

had slipped for the time being from the Empire's grasp.

As

the fleet withdrew it was simultaneously reassembling itself into interstellar

flight formation, gathering itself together like a school of fish, while each

ship geared up its feetol drive. The path of exit from Rostia's solar system

was nearly parallel to the orbital plane, and as the fleet passed close to the

primary gas giant a cursory message reached Archier from the environs scan

officer.