Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (141 page)

British conductor and promoter Sir George Smart appeared in Vienna in autumn 1825, the main reason for his visit, he said, to get the tempos of the Ninth and other Beethoven symphonies from the horse's mouth. He arrived in time to hear the September 9 tryout of the A Minor String Quartet, the second of the Galitzin group. In his diary Smart left a recollection of the occasion. It was in the inn Zum Wilden Mann, in a room rented by Paris publisher Mortiz Schlesinger. (He wanted to hear the quartet before he bought it for his firmâbut still he didn't get the piece.)

The room was stuffy and hot, occupied by what Smart described as “a numerous assembly of professors.” He found the music “most chromatic and there is a slow movement entitled âPraise for the recovery of an invalid.'” He understood that the invalid in question was Beethoven himself. Beethoven took off his coat and watched over the performers as they ran through the piece twice: “A staccato passage not being expressed to the satisfaction of his eye, for alas, he could not hear, he seized Holz's violin and played the passage a quarter of a tone too flat.” Of those attending besides the players and professors, he notes nephew Karl, Tobias Haslinger, and Carl Czerny.

41

Holz recalled that at quartet rehearsals Beethoven usually sat between the first and second violinists, where he could hear some of the higher notes. He specified the tempos and tempo changes, and sometime demonstrated passages on the pianoâor violin, as Smart witnessed. When Schuppanzigh struggled with the first-violin part, Beethoven might break into pealing laughter.

42

A couple of days later Schlesinger hosted another performance and afterward invited some of the listeners and performers to dinner. Smart observed Schuppanzigh sitting at the head of the table: “Beethoven called Schuppanzigh Sir John Falstaff, not a bad name considering the figure of this excellent violin player.” After dinner Beethoven improvised at the piano. At the end he rose, Smart said, “greatly agitated. No one could be more agreeable than he wasâplenty of jokes. He was in the highest of spirits . . . He can hear a little if you halloo quite close to his left ear.”

43

A few days later Smart visited Beethoven in Baden and got a dose of Beethovenian hospitality: a walk in the hills and, at lunch, a drinking contest. Smart reported with modest pride that Beethoven “had the worst of the trial.” He did what he could to coax Beethoven to London, patiently answering his row of objections. As he left, Beethoven dashed off a canon for him on “Ars longa, vita brevis.”

44

These days Beethoven appeared to be drinking more than usual, not the best course for a man with a bad liver.

Â

In October 1825, Beethoven returned to Vienna from a long cure in Baden after sending more fulminations to Karl, who was moving their things to a new apartment: “Continue this way and you will rue the day! Not that I shall die sooner, however much this may be your desire; but while I am alive I shall separate myself completely from you.”

45

In Vienna he had taken four spacious and attractive rooms in an apartment building called the Schwarzpanierhaus, fronting on the Alservorstadt Glacis outside the gates of the city. (It was called the Black Spaniard House because it had been built by black-robed Spanish Benedictines.) In the bedroom he installed his Broadwood and the new Graf piano. A maid and an old cook named Sali, a rare servant who seemed devoted to him, had a room for themselves. The floor of another room was piled with heaps of music in manuscript and print; its dust was rarely disturbed. After a lifetime of restless wandering, mostly within the confines of Vienna and its suburbs, the Schwarzpanierhaus was Beethoven's final residence.

His building lay diagonally across from the one where his childhood friend Stephan von Breuning lived, in the same flat the two had shared long ago before a fight broke up the arrangement. Since then there had been further breakups and reconciliations, the last estrangement flaring when Stephan objected to Beethoven's becoming Karl's guardian. Stephan worked in the Viennese bureaucracy as a councillor in the War Department, and he was ailing seriously. Now they had a warm reconciliation. The renewal of their friendship sparked Beethoven's nostalgia about Bonn, his yearning to see the Rhineland he left when he was twenty-two. He was fond of Stephan's son Gerhard, then on the verge of his teens. The boy got the inevitable Beethoven nicknames:

Hosenknopf

(“trouser-button”), because Beethoven said the boy stuck to him like one; and “Ariel,” after Shakespeare's sprite in

The Tempest

, because Gerhard was given to capering about on their walks.

Gerhard von Breuning was with his father's famous friend often in his last years, and he left a trenchant and intimate memoir. He recalled that Beethoven commandeered Frau von Breuning to oversee his housekeeping and servants. There was only so much one could do. Beethoven's quarters remained a spectacle of dust and confusion, which is why Gerhard's mother resisted his invitations to meals at his flat. When walking with her husband's groaning and mumbling friend she was distressed to find that people took him for a tramp or a madman. Gerhard remembered that once, during a dinner at the Breuning flat, his sister let out a shriek over something, and Beethoven laughed with delight because he heard it. During walks with Gerhard, Beethoven commented on the sights. On a Versailles-style row of trees in the Schönbrunn Palace grounds: “All frippery, tricked up like old crinolines. I am only at ease when I am in unspoiled nature.” On a passing soldier: “A slave who has sold his freedom for five kreuzers a day.” Gerhard became familiar with Beethoven's sarcasm, in his words and his tone of voice. As visitors noticed, even in his fulminations and pontifications there was an energy, a gusto, a mind steadily and creatively at work.

Beethoven told Gerhard about his projects, among them the Tenth Symphony that existed mainly in his mind as he worked on his string quartets. There would be no chorus in this symphony, he said. With it he wanted to create “a new gravitational force.” History would like to know what Beethoven meant by those words, if Gerhard remembered them right (like most Beethoven anecdotes, this one was written down years later).

46

Whatever that new gravitational force in a symphony was to be, likely it came from what he had learned working on the new quartets, each of which has its own gravity, its own mode of exploration.

If his rapprochement with Stephan von Breuning turned Beethoven's mind back to his roots in Bonn, that nostalgia was amplified by a letter from another of his oldest friends, Franz Wegeler, now a much-honored physician living in Koblenz. He was still married to Stephan's sister Eleonore, one of Beethoven's early loves. They had both been part of the artistic, intellectual, and progressive circle that gathered around her and Stephan's mother, Helene von Breuning, who practically adopted the teenage Beethoven. Later it had been to Wegeler that Beethoven first confessed his deafness. They had a friendship preserved by distance; there had never been a fight except for a short period of friction long before, when Wegeler was staying in Vienna. Yet they had not corresponded in years. At the end of 1825, Wegeler's long, affectionate, nostalgic letter arrived out of the blue. He addressed his old friend by his first name in French, as he had done when they were teenagers:

Â

My dear old Louis! I cannot let one of the 10 Ries children travel to Vienna without reawakening your memories of me. If you have not received a long letter every two months during the 28 years since I left Vienna, you may consider your silence in reaction to mine to be the first cause. It is in no way right and all the less so now, since we old people like to live so much in the past and especially take delight in scenes from our youth. To me, at least, my acquaintance and my close youthful friendship with you, blessed by your kind mother, remains a very bright point in my life . . . Now I view you as a hero, and am proud to be able to say: I was not without influence upon his development; he confided to me his wishes and dreams; and when later he was so frequently misunderstood, I knew well what he wanted. Thank God that I was able to speak about you with my wife and now later with my children, although my mother-in-law's house was more your residence than your own, especially after you lost your noble mother.

Â

Wegeler's admiration for Maria van Beethoven echoed her son's; he does not mention father Johann. In the letter Wegeler catches Louis up on his doings since they were last in touch. He is sixty, the family is healthy, his daughter plays Beethoven on piano, his son studies medicine in Berlin. Mama Helene von Breuning is seventy-six, living in her parents' house in Cologne. Patriarchs Ries and Simrock are “two fine old men.” Then Wegeler turns to a more serious matter, prodding his friend concerning the rumor that Beethoven was the bastard son of the king of Prussia. Beethoven knew about the story and had never publicly denied it. Wegeler asks, “Why have you not avenged the honor of your mother, when in the

Conversations-Lexikon

and in France, they make you out to be a love child? . . .

If you will inform the world about the facts in this matter, so will I

. That is surely one point at least to which you will reply.”

47

The rumor about Beethoven's paternity had appeared first in a French historic dictionary of musicians, naming the father Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm II. The

Konversations-Lexikon

in Leipzig changed the father to the even more absurd Frederick the Great.

48

Wegeler enclosed a letter from his wife. Eleonore and Louis had parted on a sour note when he left Bonn in 1792. She entreats him to visit them and his homeland. Her mother Helene, she says, “is grateful to you for so many happy hoursâlistens so gladly to stories about you, and knows all the little details of our happy youth in Bonnâof the quarrels and reconciliations. How happy she would be to see you!” She downplays their daughter's musical talent but says the girl can play his sonatas and variations. She adds that Wegeler picks through his friend's themes for variations (the easiest part) “with unbelievable patience” at the piano, and he likes the old ones the best. “From this, dear Beethoven, you can see how you still live among us in these lasting memories. Just tell us once that this means something to you, and that you haven't completely forgotten us.”

49

Beethoven was surely pleased to get letters from his old friends, but he felt no haste about replying to them or about squelching the rumor concerning his paternity. He replied to Wegeler only a year later.

Â

In January 1826, Beethoven sent the String Quartet in B-flat Major to Artaria for publication. It was the third and last of the

Galitzins

he finished. The B-flat ended up as op. 130, the second-finished A Minor as op. 132. With these three works he brought the Poetic style to the medium of string quartet and pushed the evolution of his late music into new territories. Part of what that says is that each of the quartets is even more a departure from tradition than the middle quartets and late piano sonatas. As a group they are distinct, and they are no less distinct from one another.

Still, there are threads holding the

Galitzins

together. One of those threads is the result of a change in working habit: having always sketched out pieces largely on a single line, for the late quartets Beethoven did the sketching on four staves.

50

That indicated his intention to be steadily contrapuntal and to find new textures and new kinds of part writing. On virtually every page, the quartets show that kind of attention to the individuality of the voices. At the same time that he sought a broader spectrum of color with the medium, Beethoven continued his quest for fresh ways of putting pieces together and, in keeping, new shades of feeling, new approaches to the human.

Among other developments as he made his way through these works, he veered further from the norms of logic and continuity he had learned from the Viennese Classical tradition, delved further into effects of juxtaposition and discontinuity. Here is a new intensification of the Poetic style, reaching toward conceptions that were to galvanize composers of the coming generation. In the

Galitzins

one finds more overt autobiography than before; finds Romantic irony of the self-reflecting kind (music about music, a theme about a theme); finds digressions and sudden passionate outbursts. In a review of op. 132, the critic called Beethoven “our musical Jean Paul,” citing that Romantic writer noted for his volcanic fantasy, his formal and logical eccentricities. Along with Hoffmann, Jean Paul was a key inspiration of Robert Schumann and his generation.

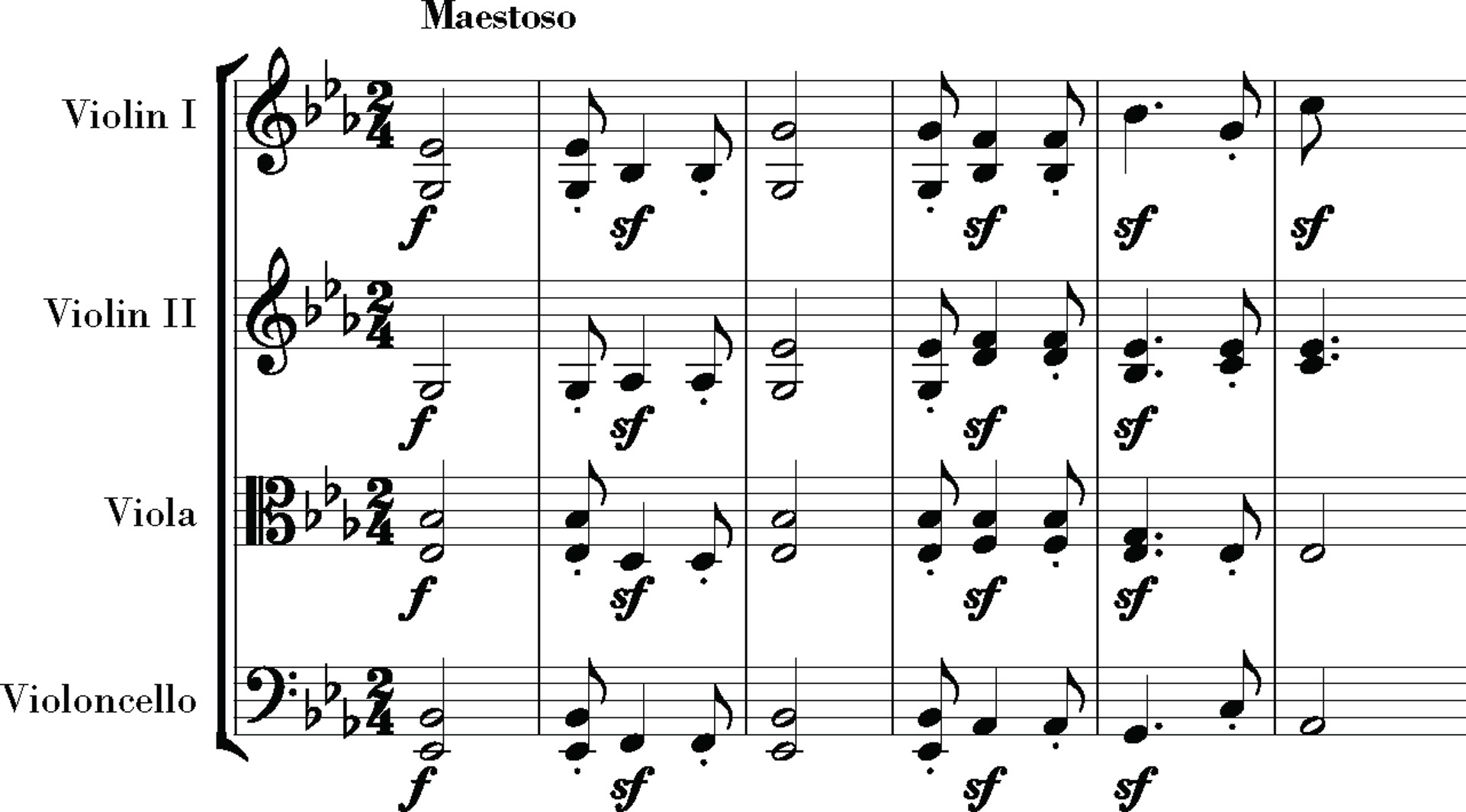

The op. 127 Quartet is in E-flat major, the key purged of a heroic tone. It is a study in lyricism expressed in the most delicate and amiable passagesâbut they are new kinds of delicacy and amiability, with little trace of the eighteenth century. It begins with six bars of robust, bouncing chords in rich double-stops that in the first measures fool the ear about the meterâwe hear a downbeat in the middle of the actual first beat:

Â