Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (70 page)

It appears that, in the wake of the ruckus, Beethoven gathered up his manuscripts, bolted the Lichnowsky castle, and walked some five miles to a nearby village. From there he found a cart and made the 140-mile, three-day journey back to Vienna. During a rainstorm on the trip, some of his music, including the manuscript of the

Appassionata

, got wet in his trunk, damaged but not destroyed. Two legends of the aftermath may or may not be true: one, that when Beethoven got home he smashed on the floor a plaster bust of Lichnowsky he had been given; two, that he wrote a note to Lichnowsky saying, “Prince! What you are, you are by circumstance and by birth. What I am, I am through myself. Of princes there have been and will be thousands. Of Beethovens there is only one.” Whether or not he actually wrote those words, it was surely what he believed, and he had every reason to.

But moral and financial issues are two quite different things. Whatever satisfaction Beethoven found in his rages and revenges, he soon realized that this paroxysm had cost him Lichnowsky's stipend of 600 florins a year. Having sunk his opera in a fit of paranoid rage, now Beethoven had tossed out a quarter or more of his income. (For a landed aristocrat like Lichnowsky, the stipend was pocket change.) He and the prince eventually reconciled to some degree, but they were never really close again, and the stipend was gone for good.

73

Beethoven, for his part, learned the relevant lesson. He never made that kind of mistake again with a patron. This was his last major indulgence in self-damaging fury.

Yet after the fight he arrived back in Vienna in high spirits. Sometimes fits of wrath seemed to leave him refreshed. He was laughing when he showed the still-wet

Appassionata

manuscript to Paul Bigot, Count Razumovsky's librarian. Bigot's wife Marie, a fine pianist, insisted on playing over the sonata on the spot. Beethoven was delighted with her sight-reading of the water-stained manuscript in his scratchy hand (though his fair copies could be legible enough). After the sonata reached print, he submitted to Marie's plea and made her a gift of the manuscript. The Bigots, especially Marie, were becoming highly appreciated friends.

At the beginning of November, a new offer arrived from Scottish publisher George Thomson. In 1803, he had asked Beethoven for six sonatas based on Scottish themes, but Beethoven's price had been too steep. A later request for chamber pieces had also gone nowhere. Thomson was a promoter and publisher of Scottish and other regional folk music. Now he offered Beethoven some piecework: arranging folk songs for a modest fee each, but with the promise of a steady supply of material. Earlier Thomson had commissioned Lord Byron, Sir Walter Scott, and Robert Burns to supply words for existing melodies. Some of the results were historic, the Burns lyrics including those to

Auld lang syne

. For arrangements, Thomson had hired German composers including Pleyel and Haydn.

Now that Haydn was no longer able to manage even piecework, Thomson turned to the newest famous German composer. The arrangements he wanted from Beethoven varied between ones for solo voice and piano to more elaborate ones for multiple voices, sometimes including obbligato parts for other instruments. Thomson insisted the arrangements had to be playable by amateurs.

74

It was never entirely clear why Beethoven agreed to take on commercial items like this that took up time and paid skimpily. The loss of Lichnowsky's stipend may have had something to do with it. In any case, whatever the constraints, Beethoven agreed, writing Thomson, in French, “I will take care to make the compositions easy and pleasing as far as I can and as far as is consistent with that elevation and originality of style, which, as you yourself say, favorably characterize my works and from which I shall never stoop. I cannot bring myself to write for the flute, as this instrument is too limited and imperfect.” It would be another four years before he sent Thomson the first consignment, of fifty-three melodies. They constitute the beginning of one of the most extensive, also nearly negligible, bodies of work in his career.

Â

The first public manifestation of what Beethoven had accomplished in this almost-inconceivable year came when the Violin Concerto was premiered by Franz Clement in a benefit concert for himself on December 23, 1806. Along with the Fourth Symphony, most of the concerto had been written at a gallop in the autumn, the finale finished, it was said, two days before the premiere. Clement may have sight-read the finale in the concert. The former child prodigy was at the peak of his fame, not a traveling virtuoso but a much-admired concertmaster and soloist in Vienna. When Clement was a prodigy of fourteen, in 1794, Beethoven had written in an album, “Go forth on the way in which you hitherto have travelled so beautifully, so magnificently. Nature and art vie with each other in making you a great artist.”

75

In the next decade he and Beethoven had come to an easy and mutually admiring professional relationship, and the concerto was written for him. Beethoven's affection for Clement was shown in one of his wry annotations on the manuscript, with a trademark pun:

Concerto par Clemenza pour Clement

, “Concerto for Clemency from Clement.”

In his most recent violin sonatas, Beethoven had been inspired by the modern French school, which had created a revolution in playing based in part on the relatively new Tourte, or “Viotti,” bow. Its inward arc, rather than the Baroque outward-arced bow, made possible a stronger tone and a wider range of effects. The French style was familiar to Beethoven through the playing of Rodolphe Kreutzer and George Bridgetower, and through the well-known concertos of Giovanni Battista Viotti, like Cherubini an Italian-born composer who found his fame in Paris. Viotti's concerto style, which came to be known as simply “the French violin concerto,” involved bravura effects, forceful attacks, and a greater repertoire of slurs, all enabled by the new bow. These concertos also expected a more robust tone from the soloist. All this in turn helped associate French concertos in the audience's mind with the atmosphere of the Revolution. Along with the development of the modern bow, pre-1800 violins, even the most precious Stradivaris and Guarneris, were being taken apart and fitted with longer fingerboards, a higher bridge, and a thicker sound post inside. In addition to the new bow, these adaptations gave the violin more power and brilliance, even though the strings remained the traditional gut.

Still, as with Viennese piano makers, violinists in Vienna were slow to adopt new trends. Beethoven's string players in those days probably used a mixture of old- and new-style instruments and bows. Clement himself was an old-fashioned player who played on a traditional fingerboard with a traditional bow. He was noted more for his elegance and delicacy, and his sureness in the difficult high register, than for flash and power.

76

So the concerto Beethoven wrote for him had little of the dramatic cross-string chords and virtuosic bow work of the more French-style

Kreutzer

Sonata. Inspired by Clement, the concerto did involve a great many passages in the high reaches of the E string (which Beethoven had avoided in the early violin sonatas). The stratospheric violin writing was perhaps a progressive element in the Violin Concerto, but otherwise the piece was largely devoted to a lyrical style, which Beethoven, writing as fast as he could get the notes down, pushed into a new dimension in concertos.

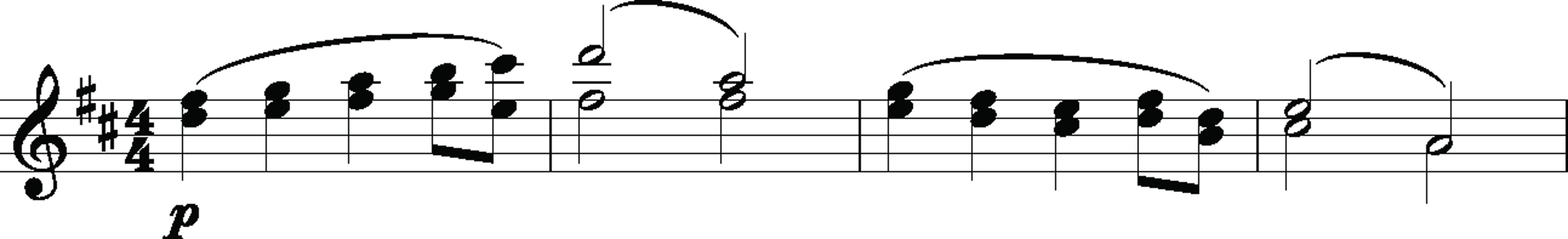

The Violin Concerto is unique from the first sound: it begins unprecedentedly with a timpani solo marking the four beats of the first measure and the downbeat of the second, where the winds enter on a quietly soaring theme marked

dolce

, “sweet.”

77

The opening gesture says two important things about the music to come: first, that timpani rhythm is going to be a leading motif of the first movement; second, its simplicity heralds a piece that is going to be made of radically simple elements: rhythms largely in quarters and eighths, most of the phrasing in four bars, flowing melodies made largely out of scales. Many of Beethoven's themes had always been fashioned from bits of scales; here that is carried to a transcendent extreme. In keeping, the harmony is simple but with touches of striking color, unexpected shifts of key, excursions into minor keys that arrive not like dark clouds but as colorations and intensifications. The lucidity and simplicity of the material contribute to the singular tone, serene and sublime, marked by the soloist singing on top of the orchestra in the highest range of the instrument.

All that is to say, this is not a heroic or a particularly virtuosic or dramatic concerto. The opening timpani stride might imply a military atmosphere like the openings of his piano concertos, but the music does not go in that direction. And there is no readily discernible dramatic narrative of the kind in which the contemporary Fourth Piano Concerto is so rich. Call the main topic of the Violin Concerto

beauty

in the visceral and spiritual sense that the time understood it.

When things are stripped down to the simple and direct, every detail takes on great significance. So it is in the enormous first movement, with its sure-handed proportions, its subtle touches of color and contrast that keep the music riveting and moving. The orchestral exposition unveils three rather similar themes, all of them flowing up and down a D-major scale. The quarter-note tattoo introduced by the timpani underlies everything, including patterns that speed it up to eighths and sixteenths.

An out-of-nowhere D-sharp intruding on the placid D major creates more color than drama. That pitch will summon later harmonies and keys (mainly B-flat) in the movement. In the orchestral exposition, the main contrasting keys are B-flat and F, surrounding the home key not with the expected dominant but rather with thirds above and belowâan increasingly common Beethoven pattern. Here they are placid mediants in the flat direction, generating warmth rather than tension. The unusual element is the lack of tonal movement, each theme first heard in D major, the second one feeling more like the

Thema

proper of the movement.

Â

Â

The violin enters on bravura octaves that soar from the bottom of the instrument up into the high range, where the soloist will live much of the time, devoted more to spinning out lace than thematic work. This is a symphonic concerto in which the soloist is not a heroic or even distinctive personality so much as a kind of ethereal presence floating through and above the orchestra. After an improvisatory quasi-cadenza, the violin seems to improvise on the first theme high in the clouds while the winds play it straight. The development section is striking mainly in its placidity and its melodiousness, in contrast to the usual fragmentation and drama of developments. The first movement, like the others, requires a cadenza; Beethoven supplied none of them.

If it is possible, the gentle second movement is even more exquisitely lyrical than the first. Its form takes shape both simply and unusually as a serene theme over a repeating bass pattern, variations that are largely rescorings of the theme to which the soloist adds quasi-improvisatory filigree. After three variations, two new themelets, call them B and C, stand in for a couple of variations, and an extension of C serves as coda.

78

An old Viennese legend says that the leaping 6/8 “hunting” theme of the rondo finale was written by violinist Clement. That makes sense for two reasons: Beethoven had to write the finale in a tremendous hurry and may have seized the nearest thing to work with; and in style, the tune seems a throwback to the gay and slight rondo finales of his youth. Still, his treatment of the theme is fresh despite its conventions (including a hunting episode for horns). The total length is only about a third that of the first movement.

79

Its vigorous joyousness is the payoff of a work of serene beauties.

The enormous program in Vienna, where the concerto premiered, had the time's usual mixture of genres and media. It included overtures by Méhul and Cherubini, a Mozart aria, a Cherubini vocal quartet, and vocal pieces by Handel. In the middle of the Beethoven concerto Clement performed one of his trademark tricks, playing a piece on a violin with one string, upside down. A review in the

Wiener Zeitung

said, “The superb violin player Klement [

sic

] also played, among other exquisite pieces, a violin concerto by Beethhofen [

sic

], which was received with exceptional applause due to its originality and abundance of beautiful passages. In particular, Klement's proven artistry and grace . . . were received with loud bravos.” That said, the reviewer turned the back of his hand:

Â

The educated world was struck by the way that Klement could debase himself with so much nonsense and so many tricks . . . Regarding Beethhofen's concerto, the judgment of connoisseurs is undivided; they concede that it contains many beautiful qualities, but admit that the context often seems completely disjointed and that the endless repetition of several commonplace passages can easily become tiring. They maintain that Beethhofen should use his avowedly great talent more appropriately and give us works that resemble his first two Symphonies in C and D, his graceful Septet in Eâ, the spirited Quintet in D major, and various others of his earlier compositions, which will place him forever in the ranks of the foremost composers.

80